There are several museums, art galleries, public libraries, theatres, and history centres throughout India. Though numerous of these buildings are now standing empty and fossilised, much like the artefacts they were meant to display and save, In the past, the government was primarily responsible for building India’s cultural infrastructure, which frequently resulted in stagnation.

The historical context of the nation has undergone an obvious shift during the previous 20 years. Numerous cultural projects have been started, frequently in collaboration with city authorities, thanks to increased interest from private entities.

These present-day initiatives seek to highlight the diversity of Indian historical and cultural traditions in order to elevate India as a prized tourist destination for the expanding middle class.

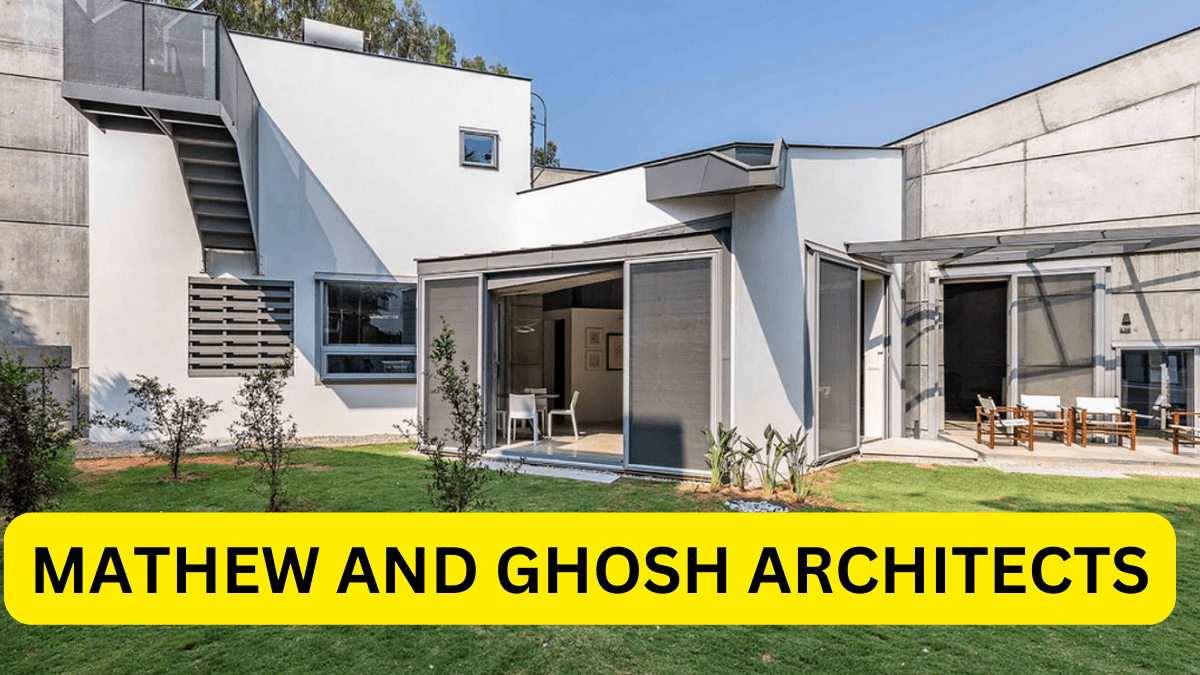

With renowned establishments like the Ranga Shankara Theatre, the Indian Music Experience Museum, the recently opened museum of art and photography by Mathew and Ghosh Architects, and the impending Bangalore branch of the Science Gallery, the municipality of the Bangalore area in the Indian state of Karnataka is a location that has experienced enormous growth in this regard. Nisha Mathew Ghosh, principal architect and partner at Mathew and Ghosh Architects, remembers how their competition idea for Freedom Park in the early 2000s signalled the start of an expanding struggle.

In a chat with ArchDaily, she says, “The government, which had never before engaged with Indian architects, proceeded to collaborate with the private world to facilitate infrastructural construction.” In the winning entry, Mathew and Ghosh Architects proposed a democratic urban park for the twenty-first century that would incorporate a variety of cultural activities. The undertaking set the city’s wheels in motion, inspiring a plethora of initiatives like the construction of sidewalks, public restrooms, and the renowned Church Street, a pedestrianised private-public street.

In the wake of Freedom Park’s opening, a number of well-known businesspeople began approaching local government agencies with ambitious plans for the city and large sums of money. Partnerships between the government and commercial sectors in infrastructure are becoming more common in Indian cities’ national architecture. The Bangalore International Centre (BIC), created by the architectural firm Hundred Hands, is additionally a part of the greater narrative of private initiative driving initiatives for the city.

The BIC was designed as a venue for community-wide free cultural events to promote intercultural discourse and advance ideas across cultures, faiths, geographies, communities, and economics.

A flexible area for assembly is organised behind a glass facade that visually connects the centre to its surroundings and houses an auditorium, seminar rooms, an art gallery, a library, a restaurant, and other amenities. “The BIC’s stewardship is what makes it a successful and well-liked cultural space in the city. The building has been occupied by people who have changed the space to a different location’, says Bijoy Ramachandran, Director and Partner of Hundred Hands. Architectural expression, while playing an important role, is not the sole factor determining the success of a cultural infrastructure project.

Curation and management play a crucial role in contributing genuine value to the space. Cultural institutions become abandoned assets when the public lacks ambition and support. The challenge is to make sure that these venues last for a long time; building cultural infrastructure is the easier part. It is essential to introduce a suitable, inclusive curriculum. Finally, Ramachandran says Even if the government is showing a growing amount of interest in creating interactive cultural infrastructure, public-private partnerships are the ones that have the most success.

.Due to a developing contemporary music and art scene and a higher quality of living, the demand for cultural venues in the nation is increasing, and Indian and foreign architects are creating models that will help promote the nation’s changing image.

The achievements of experienced architect Charles Correa in India’s cultural landscape can serve as a model for architects looking to the future. Through their architecture, his ideas for the Gandhi Memorial Museum and Jawahar Kala Kendra radiate an intrinsic feeling of inclusivity and freedom. In a nation with a populace as diverse as India’s, it is necessary to not just incorporate but also encourage all societal groups to take an active role in and own the whole procedure. India’s modern cultural architecture differs significantly from its historical models. ”

Post-independence projects, like Correa’s National Crafts Museum, reflected a deep awareness of the country’s people, economy, culture, and fine arts. According to Soumitro Ghosh, Principal Architect and Partner of Mathew and Ghosh Architects, “They had a wider vision that was shared by many individuals and came more from a socialist stance. He detects a change in modern cultural projects’ aesthetics towards what he terms an “architecture of entertainment. These initiatives display an aura of unease as they chase after goals of international acclaim, meet stringent deadlines, and make overt political remarks. Spaces that are unsteady and cut off from methods of influencing both culture’s keepers and its consumers are the end result.

Small-scale, locally focused initiatives and larger infrastructure in a city and beyond can be seen as two distinct sorts of cultural projects in India. More chances for the meeting of like-minded individuals exist as India’s population grows and its cities get denser.

India’s cultural architecture is based on shared responsibility and cooperative efforts between the people, businesses, and the government. The success of these initiatives will be determined not by the rise in the number of tourists but rather by the diversity of people who feel at home there.