The big, old trees in Punjab’s villages have long served as mute witnesses to all that the inhabitants have been through. From the agony of partition in 1947 to the dark militancy days of the 1980s, the elderly trees, raised by rural families as children, have seen, heard, and buried many bitter realities within them.

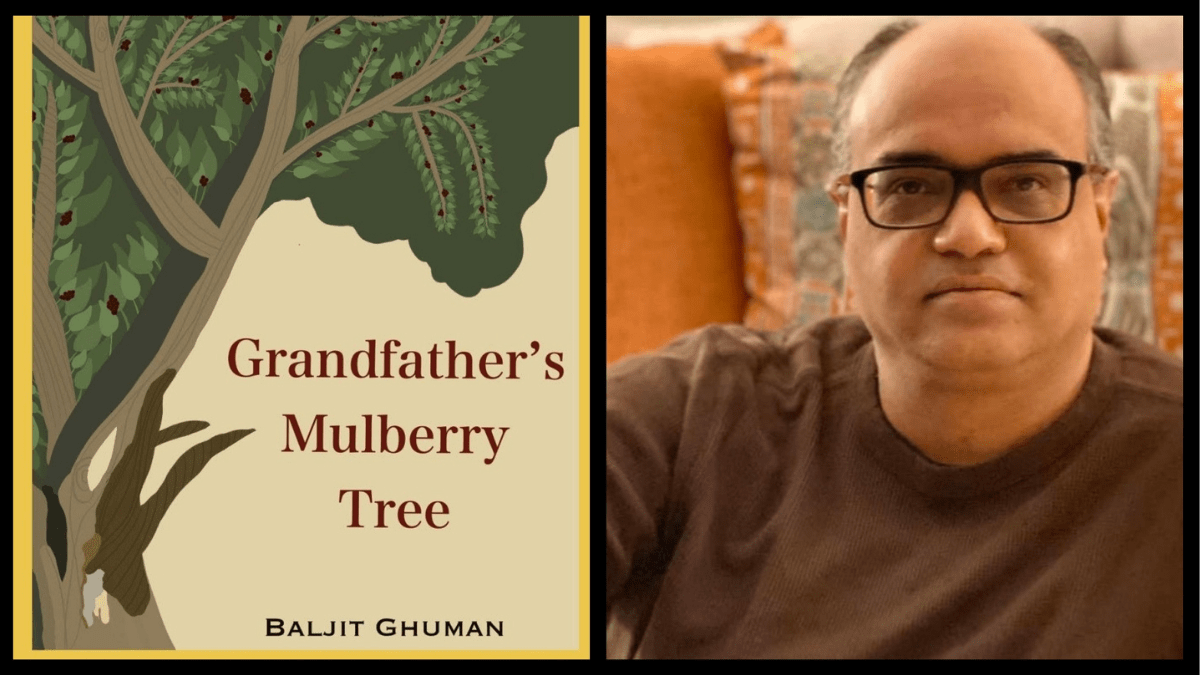

Baljit Ghuman (50), a Canadian Sikh, wrote Grandfather’s Mulberry Tree, which is a dedication to a family’s favourite tree. The author takes readers on a journey as an adolescent Sikh lad through the stormy Punjab of the 1980s, when militancy was at its zenith and trees and sugarcane fields were silent witnesses to the extrajudicial killings of Sikh youngsters by Punjab Police.

The book is inspired by the mulberry tree that bloomed in full bloom in the home of Ghuman’s maternal grandpa, whom he affectionately referred to as “Bhapa ji”.

Ghuman was born in Batala and spent most of his childhood in Jalandhar before moving to Canada as a teenager. Ghuman’s father, Major Baldev Singh, an ex-serviceman and alleged Khalistan militant who had taken voluntary retirement from the Jat regiment, was also shot dead during the militancy period. Ghuman is now an autism and neurodiversity advocate in Toronto and runs an organisation called “Sikhs for Autism” to raise awareness about disabilities.

According to Punjab Police, Major Baldev Singh was working hand in hand with controversial Khalistan militant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and had given refuge to one of his bodyguards, Manbir Singh, at his Jalandhar farmhouse, from whence they were detained. Baldev was held in solitary confinement for two years before being shot dead outside his Jalandhar home in June 1990, allegedly by police informers (CATs). Ghuman, however, adds that his father was a ‘human rights activist’ who would challenge police over missing Sikh teenagers, arrange protests against bogus encounters and battle to bring bodies of slain youths back for last rites.

However, the novel is written from the perspective of a youngster. It demonstrates how a young mind interprets catastrophic experiences, comprehends the life cycle, and interacts with relationships. Ghuman’s constant companion on his voyage through Punjab in the 1980s, when every new day brought word of someone he knew being missing or being shot, was the mulberry tree at his grandfather’s house.

Following an alleged extra-judicial death near the family’s home, an excerpt from the book reads: “Both the mulberry tree and Bhapa Ji watched the horrible event. I can’t image how the sugar cane plants felt when they were utilised as a cover to commit a murder… I was young, but I understood what had happened. In a false police encounter, the officers killed a Sikh guy. I knew the young Sikh man’s family would never learn what had happened to him. I knew the police would never hand over dead bodies like his back to their families, since corpses can talk, and their wounds will convey the story of execution and murder.

The author claims that he had frequent nightmares of his own father being shot dead, and that one day, it became a reality.

The “Bhapa ji” lived and died alongside his mulberry tree. And when the writer’s grandfather left the earth, carrying with him several memories of Punjab’s terrible days, the mulberry tree did not leave him alone.

When asked why he chose to write about this, he explains that due to violence in 1980s Punjab, he was unable to attend school for nearly three years. “I’ve always struggled with the language. So I chose to write about how violence affects childhoods, like it did for me and thousands of others in Punjab,” he explains.