Whether defending one’s own territory or battling for justice, the human mind has a predisposition to pit oneself against another, or us against them. right against wrong. Kabir challenges us to see beyond simple dichotomies .

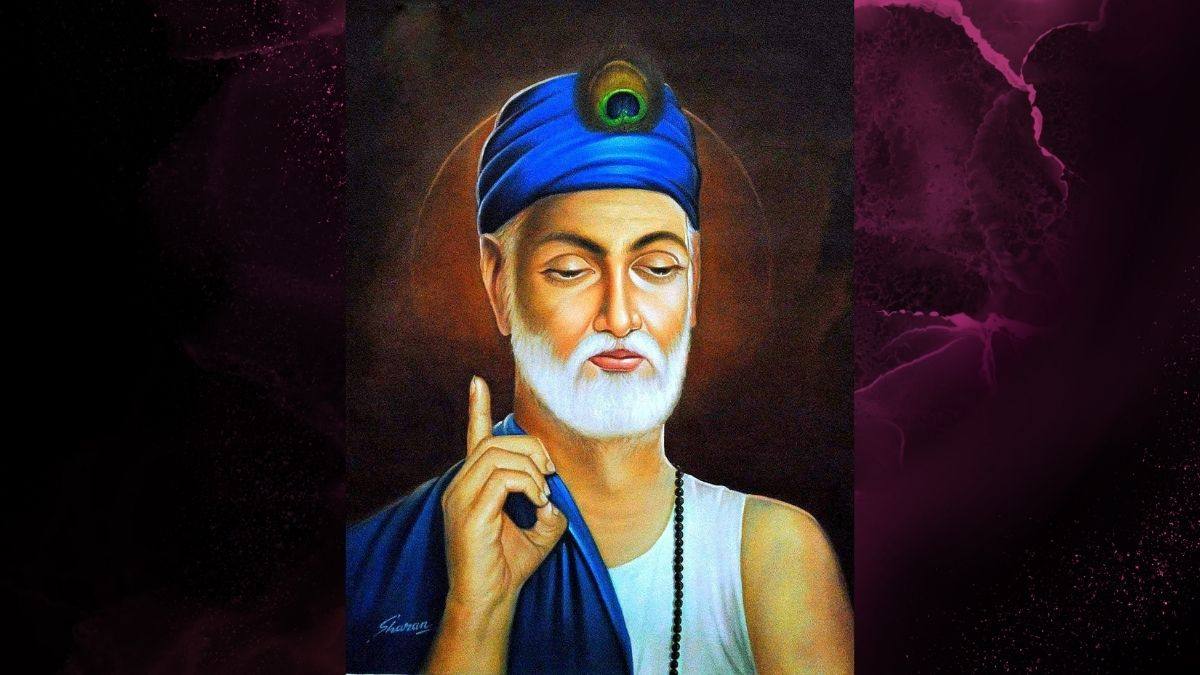

Kabir is a vague historical character who lived in Varanasi by the Ganga in the fifteenth century. Very little about his life is known for sure. Conversely, a multitude of legends have emerged surrounding him. From his own statements, we do know that he was a weaver from the “low caste” who was illiterate. Nonetheless, his poems and melodies have endured and flourished for more than five centuries because Americans have never ceased singing or repeating them. It is likely that he was born into a Muslim family and had a wife and kids, although different people have different opinions on how likely these facts are.

However, Kabir is not only a historical person. He stands for a current of ideas and emotions that the common Indian people have shaped to suit their own requirements. He stands for a voice that people must hear, use for speech, and use for singing! Being able to transform into a voice that can sing, breathe fire, and provide comfort simultaneously, hundreds of years after one’s death, is already an amazing accomplishment. The fact that Kabir still speaks to us with the same fervour and relevancy as he did in his own day is another wonder.

- Kabira khada bazaar mein, liye lukaathi haath.

Jo ghar jaare aapna, chalo hamaare saath.

Kabir was standing in the market. He’s still out in the marketplace. He doesn’t converse with us from the far solace of a forest retreat or a mountain summit. He’s here now, thank you very much. However, he also sees beyond what our typical battle-ready modes show us. He extends an invitation for us to move out of our comfortable, secure emotional, intellectual, and psychological cocoons. He’s asking us to get in touch with a higher truth. We may believe that we are facing difficulties never seen before in history, that oppression, bloodshed, and conflict are unchecked overseas, and that things have reached a breaking point from which nothing can possibly escape.

- Sab aaya ek hi ghaat se, aur utra ek hi baat.

Beech mein taati bharam ki, to ho gaye baarah baat

Raam Rahima ek hai, aur Kaaba Kashi ek

Maida ek pakvaan bahu, baith Kabira dekh

Kaaba phir Kashi bhaya, aur Raam hi bhaya Rahim

Mot choon maida bhaya, aur baith Kabira jeem

As we can see, Kabir does discuss unity. However, Kabir is pointing out a unity that transcends conventional religion and all other forms of human division. And unless this truth is understood as a lived experience (Kabir doesn’t rely on religion, authority, theory, or ideology; he “eats” and “watches” it himself), all efforts to create a flimsy façade of social harmony will ultimately fail. This dish needs to be tasted in person. A true sense of harmony, both inside and outside, is brought about by this exquisite, jheena (subtle) flavour that must be experienced for oneself. For example, diversity cannot be forced upon someone. It is necessary to cultivate respect for and acceptance of diversity of all kinds.

- Kabir kuaan ek hai, panihaari hain anek, Bartan sabke nyaare hain, par paani sab mein ek.

Humans naturally create enemies, whether they are defending their own area, pursuing justice, or striving for a “better world.” We are each other and ourselves. Angels and devils, good versus evil. When we make adversaries, particularly those who are truly “evil,” we lose our sense of reality. It can seem illogical to do this. “But there are really evil people in the world; that is the actual reality,” is the typical response to such an objection. There are undoubtedly some people who embody evil and some who embody goodness. Who, though, is to judge? Every side believes the other to be more wicked than they are. Every side often believes that it is fighting for justice, progress, or the truth.

- Jab lag meri, meri kare, tab lag kaaj ekai na sare.

Jab meri, meri mati jaaye, tab Hari kaaj savaare aaye.

The fixation on “I” and “mine” is not limited to individuals who are power-hungry or cruel. It is a trait shared by all members of the human race, not just the nice ones. This has a significant impact on our behaviours and attitudes. Being humble, listening, perceiving without the ego’s agitations, and acting from a position of higher knowledge and wisdom are all necessary to overcome this divisive tendency in oneself. It entails understanding when and how to take action as well as when and how to refrain from taking action. It ties one’s deeds to the power of the truth. We cease to regard our deeds as superior to those of others. We also cease worrying about reaching specific objectives.

- Kabira ishq ka maata, dui ko door kar dil se

Jo chalna raah naazuk hai, haman sir bojh bhaari kya?

Love is not a frivolous, sentimental topic that should be avoided in all “serious” discussions. Our essence is love. Love gives our acts a great deal of power. In addition, it keeps us light and unburdened by our high expectations—of the world, of ourselves, and of others. It encourages happiness and optimism as well as the pursuit of individual and societal freedom, both of which are vitally important in any circumstance. Everything changes, including, most significantly, the person who acts, when our actions originate from this source.

- Haan kahun to hai nahin, na bhi kahyo nahin jaaye.

Haan aur na ke beech mein, mera satguru raha samaaye.

There is no separation between “the divine” and “this world,” and action and thought are not mutually exclusive. Kabir’s poetry is infused with a sense of the holy. Kabir is critical and involved in society at the same time. However, he bases his harsh societal criticisms on his belief that there is something more than what is simply human—that is, something sacred and elevated. In this sense, Kabir is not a “humanistic” poet. His answers do not stem from a noble and well-intentioned mindset. The poet of the sacred is Kabir. Love is another term he uses to describe this. His courage to communicate the harsh truth, even if it puts his own safety in jeopardy, comes from his feeling of the holy, or love.