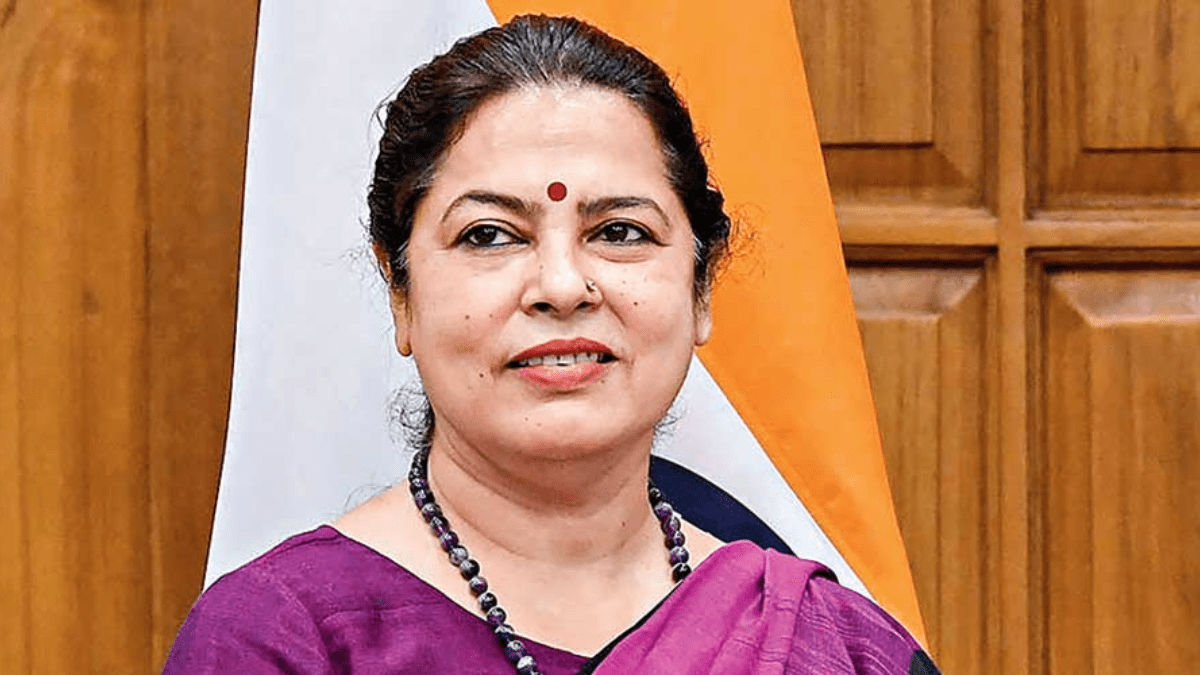

While visiting Kozhikode the other day, Meenakshi Lekhi lost her temper. At the end of her speech, the Minister of State for External Affairs and Culture was furious that the audience had not responded to her scream of “Bharat Mata ki Jai” with enough fervour. It didn’t seem like she knew she was encountering a cultural rather than a political barrier.

Lekhi could hardly have been in the dark regarding the political inclinations of the event’s organisers. Neither the United Democratic Front nor the Left Democratic Front organised it. With the exception of certain national occasions, the two alliances that control Kerala politics are quite reluctant to give BJP politicians a platform. Minister Lekhi’s assessment would be considerably more debatable if she had expected supporters of either Front to recite the Hindutva slogan.

Given the BJP affiliations of the two cultural organisations acting as joint hosts, it ought to have been simple to deduce that the lacklustre reception was unrelated to political preferences. The Delhi politician appeared to be unaware that Malayalis find it difficult to pronounce the phrase. Of course, this hesitation to bring it up has nothing to do with a dislike for Hindi. Without any knowledge of the local language, one might not be able to order takeout, get a haircut, or have house repairs done in Kerala today. Hindi aficionados don’t seem to get that their language is becoming more and more common in the nation without their help. The procedure is slowed down by their constant repetition of the subject.

This presumption—that your culture is superior—follows another, according to which individuals from other cultures must be forced to adopt yours. In this instance, the more fundamental presumption is based on the idea that both cultures are part of a larger whole, in which yours is a superior culture. This whole system of beliefs is ridiculous.

The majority of people involved in the Kozhikode incident were presumably Hindus, if not all of them. Alternatively, the individual who initially proposed the phrase believed that all of them were Hindus and would be open to reciting it. From then on, it appears that she came to believe that the “truer-to-the-creed” northerners had a duty to instruct the Southerners in the appropriate practices of Hinduism. It is full of contempt that can be directed in both directions due to ignorance.

I was horrified to see how little my peers from the Hindi belt knew about Hindu lore when I first entered college in Delhi in the 1970s. They had probably grown up watching Ram Leela performances, so they were familiar with the general idea of the Ramayana. Nevertheless, they appeared to be mostly ignorant of the subtleties, such as the ethical and tactical conundrum raised by Ram’s decision to choose Sugriva against Vali or the inner turmoil Khumbakarna went through in defending a brother he thought had committed a terrible wrong.

It appeared that their knowledge of the Mahabharata was considerably less. That was about it—five versus a hundred, with a dice game in between, and Krishna pronouncing the Gita on the battlefield. Questions about the father of Veda Vyasa or the titles of the generals of the seven Pandava divisions had to be removed from hostel quizzes since they would have given easy scores to Odiya and Madrassi students. We all had a solid foundation in the epics thanks to reading C. Rajagopalachari’s kid-friendly adaptations as children.

Later on, it was discovered that there have always been outstanding scholars of the Shastras and Vedas in every part of the nation. Moreover, the destruction of something valuable is the result of any attempt to destroy Sanatana Dharma. I am not qualified to perform intricate rituals, much less conduct household pujas, due to my caste identification. I am nonetheless in awe of the austere majesty of Vedic traditions, even after nodding acquaintance with a “somayagam” and an “adhirathram.”

However, ardent Sanatanis must also acknowledge the legitimacy of other mores. The idea that all Hindus must be vegetarians, that our ancestors did not hunt and did not consume the wildlife they had killed, came from where or when? While Dasharatha went hunting, wasn’t he cursed? When Arjuna and Siva (as Kirata) shot the boar at the same time, were they competing for gold in archery?

Over the years, one has come to understand that Hinduism embraces all forms of communication with the Almighty One, including private, solitary meditation, big temple prayer, the practice of viewing one’s work as worship, and more. Its lack of force is likely its most distinctive feature. It’s not necessary to push yourself to behave or internalise beliefs. You come to realise that pressuring oneself or others to comply serves no useful purpose. Hinduism does not have a single centre, dogma, or set of ceremonies because of this. It is absurd to transform Hinduism into something it is not. Hinduism permeates you and rises to each person’s unique level.