Know How Ameen Sayani Healed The Strong Soul Of India

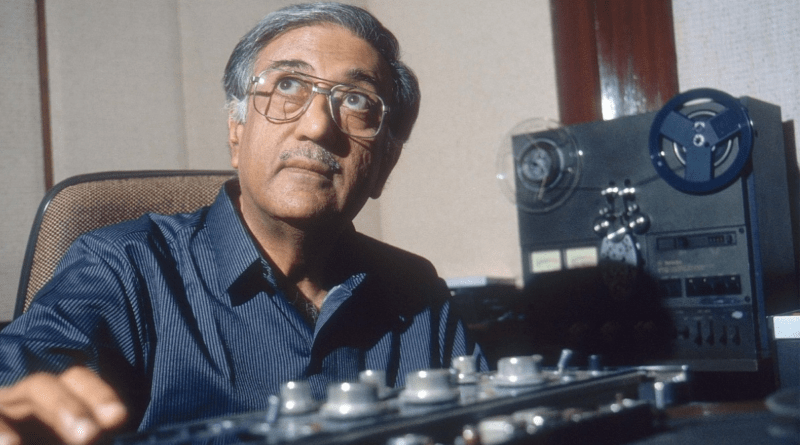

A picture was discovered of the one and only Ameen Sayani taken by his son at the National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA), Mumbai, just a few days after his untimely demise. In the photo, August 2019 is written.

We have developed a close admiration for him.

Sayani, in addition to being an intriguing performer and India’s first radio DJ, had made a significant but little-known contribution to the country’s cultural unification.

He contributed to the creation of a universally liked and understood mass medium by making Hindi film music more widely known on radio across the diverse and frequently at odds subcontinent. The 1500-person hall abruptly broke into spontaneous applause in honour of Ameen ahab. He got up from his chair as well to accept the gesture and offer a bow.

It was one of his best hours. Even at 85 years old, Ameen Ji was in such good shape. For those who are unaware of the entire tale, it started in August 1952 with his presentation on Radio Ceylon, where he introduced music from Hindi films. Just five years before, India had consisted of 565 kingdoms, or separate princely states, 14 British Indian provinces, and one nation.

Despite partition riots and interregional conflicts, the nation was united physically, but it lacked both genuine emotional unity and a single language. Since English was exclusively spoken by the educated, people spoke hundreds of other languages. However, many Indian regions opposed the rigid adoption of Sanskritic Hindi as the official national language.

During this period, the Indian government also mandated that citizens limit their music consumption to ghazals and sophisticated classical music. B.V. Keskar, the first minister of information and broadcasting, labelled Hindi film music as inferior “laralappa” and outlawed it entirely from playing on All India Radio, the monopoly radio network.

Ironically, it was also Bollywood’s heyday, a time when everyone was mesmerised by the music’s eerie quality and beautiful lyrics and melodies. Because of this, even though such popular music was prohibited on national radio, the masses were clamorous for it. A very small fraction could afford to visit movie theatres, and even fewer had access to pricey gramophones.

A Hindi film music series on Radio Ceylon was sponsored by CIBA (Chemische Industrie Basel), a Swiss business that sold Binaca toothpaste in 1952. Binaca Geetmala was the name of the game, and Sayani was the “jockey.” It quickly became an incredible hit parade of well-known songs, thanks to his amazing introductions and interventions.

Every Wednesday, from 8 to 9 p.m., it was televised. Because of the strength of Ceylon’s British Second World War transmitters, which were intended to reach war-torn Southeast Asia, most of India could hear Binaca Geetmala. People stopped everything on Wednesday nights to listen to it because it was so legendary; in the process, they picked up the easy Hindustani language, which was laced with romantic Urdu phrases and endearing colloquialism.

However, even as Sayani’s popularity reached unimaginable heights, Keskar and the powerful Akashvani refused to recognise the voice of the people. All India Radio was forced to give in after facing opposition and criticism from the public for five years, and in 1957 it launched Vividh Bharati, a famous film music channel modelled after Ameen ji’s programme.