Breakthrough Now: Nandu’s Passing Marks the End of An Era in Good Local Indian Music

Between 1838 and 1917, Indians were brought in as indentured labourers, bringing with them their languages and ways of life. In a nutshell, they were carriers of multiple cultures, with 16% from South India (“Madrasis”) and 12% Muslims among the majority Hindus. However, as rural peasants, their perspectives, practices, and “products”—the “3 Ps of culture”—shared strands of commonality that quickly coalesced around the majority North-Indian Bhojpuri variant.

On the plantations, the first era of “Indian music” was represented by the folk songs they brought from India, which provided a respite from the never-ending toil demanded of them, just as “back home.” These songs were of several genres, including “work songs” such as “jatsar” (while grinding grain) or “ropani” (while planting rice); life cycle songs like weddings songs of the “matikor” or “dig dutty”; childbirth (sohars); funeral songs; songs of the seasons like saavan, kajri, etc.; songs of parting (bidesia); and the call-and-response biraha. Religiously, there were Hindu Bhajans and Dhoons; happy Phagwah songs; Muslim Qaseedas and Qawalis; and South Indians singing to their village deity, Mariamman.

There is a distinction between the aforementioned “little tradition” and the “great tradition” of the upper classes, which in Indian music includes the raag-based genres that predate the Moghul court. While the latter was not replicated in Guyana, after indentureship ended, an acknowledgement was made for the introduction of an indigenous “classical music” known as “taan singing.” The style is similar to classical styles such as dhrupad, tillna, ghazal, and thumri, but it is quite different. It has been suggested that the name is derived from “Tan Sen,” one of the greatest classical musicians of the Mughal Court. This era of folk and taan singing continued into the 1940s, and Mohan Nandu’s father was a well-known taan singer.

The Biraha tradition lends itself to witty topical compositions in a blend of Bhojpuri and English, resulting in a vibrant art form. In 1962, ethnologist Ved Vartik gathered and recorded thousands of songs from across the country.

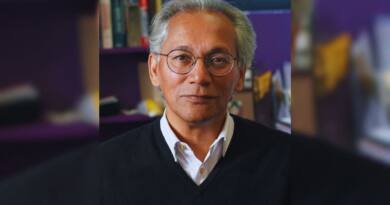

The introduction of Indian “talkies” with playback singing in Guyana at the end of the 1930s signalled the end of the first era of local Indian music, and the second era began in the 1950s, represented by Mohan Nandu and his great contemporary Gobin Ram. This new era coincided with the Great Exodus from the logies to new villages, which was prompted by the Sugar Industry Labour Welfare Fund in 1947. TMohan Nandu’s parents would have relocated from Cornelia Ida’s logies to Anna Catherina’s housing development.