The Outstanding And Tantalizing Ancient Sculptures Exhibition

While much of India’s ancient history is being rewritten, it is necessary to consider how historic museum collections might be reinvestigated to serve as historical research tools and to redefine India’s cultural legacy.

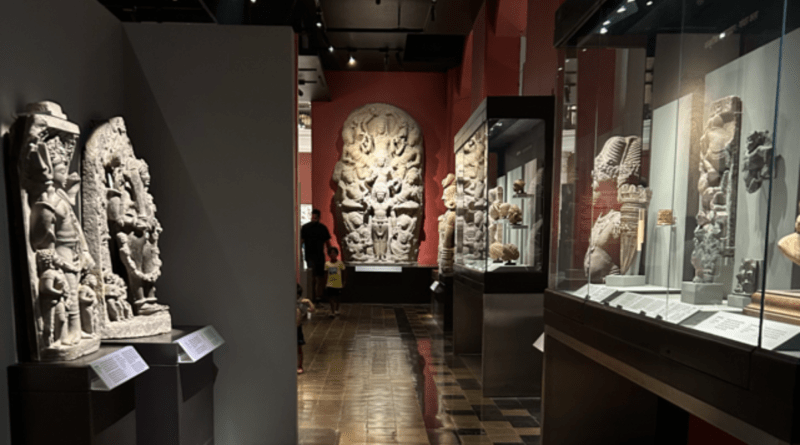

Most museum collections in the country are neglected, continuing to adhere to 19th-century orientalist beliefs, with artefacts from the past locked in time and gathering dust. It was therefore refreshing to observe how the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS) in Mumbai is discovering innovative methods to reinterpret its historical collection.

The museum is now organising an exhibition called ‘Ancient Sculptures: India, Egypt, Assyria, Greece, and Rome’ in collaboration with three other institutions: the British Museum, the Getty Foundation, and the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. The show is part of CSMVS’s wider ‘Ancient World Project’, which was created to mark 75 years of Indian freedom. The purpose is to introduce works of art from other civilizations to Mumbai to broaden understanding.

This is one of the few museums that uses old sculptures as historical evidence to discover cultural ties between different ancient civilizations, and it tells an extraordinary story. The show stresses India’s prominence in the ancient world by highlighting the religious, architectural, and philosophical themes underlying these sculptures, rather than just comparing Indian art to the classical cultures of Greece and Rome, as is sometimes done.

Most significantly, for the first time, we observe a shift in curatorial perspective. The show was designed with Indian museum visitors in mind, many of whom may never have the opportunity to travel. The idea is to provide children with the opportunity to explore art and culture from other corners of the world.

Encouraging Indian audiences to interact with these ancient sculptures, ask relevant questions, and analyse the pieces using their own cultural understanding could reveal a plethora of meanings within these museum artefacts. A second goal of the exhibition is to engage with local schools and institutions, encouraging students and educators to broaden their learning beyond the classroom and to see material culture and museum collections as important sources for historical methodology.

The study of ancient history remains framed from a European/Mediterranean perspective. This kind of audience interaction will ideally create a new sort of knowledge tradition while also nudging historians to write more global histories of the ancient world.

Artwork in exhibitions

Academic interest in India’s ancient sculptures began in the late 18th century, when European travellers and officers of the English East India Company began to visit various parts of the subcontinent, surveying its topography and people, learning about its history, and documenting its architectural and archaeological remains.

Religious sculptures were originally gathered for their great craftsmanship, but they eventually became objects of intellectual interest. Because of their several heads, multiple limbs, and sensuous bodies, they were frequently described as monstrous, barbarian, vulgar, and irrational. Sculptures were initially sent to Britain as imperial keepsakes, where they were scientifically investigated and critically evaluated, particularly in contrast to those from classical Greece and Rome.

While the intellectual focus at the time was on collecting Indic manuscripts and inscriptions and translating, deciphering, and interpreting them, sculptures were viewed solely as archaeological artefacts, studied for their aesthetic qualities, and evaluated for how accurately they represented related ancient texts.

The colonial British administration established museums in India to conserve the country’s rich archaeological and ethnological treasures. Calcutta’s first museum, the Imperial Museum, opened in 1814 and was later renamed the Indian Museum.

Sculptures in Discussion

The ‘Ancient Sculptures’ exhibition is one of those rare occurrences that addresses several of these gaps. Ancient sculptures are designed to trace networks of relationships and the exchange of knowledge traditions between India and the rest of the globe through artistic themes, ideologies, and religious beliefs, rather than making civilizational comparisons.

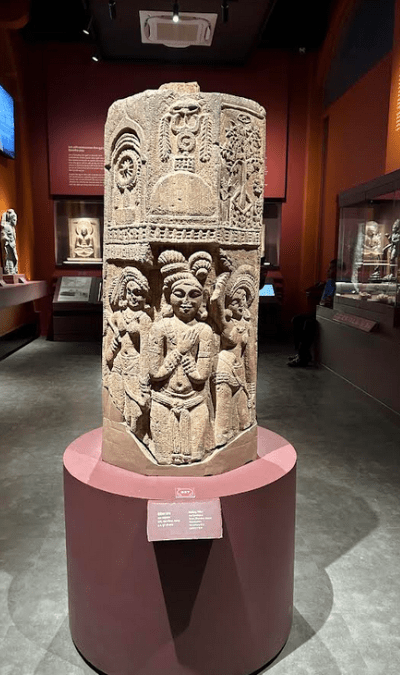

When guests enter the CSMVS’s majestic Indo-Saracenic edifice, they are greeted with a stone lotus medallion, a part of the huge Amravati stupa.

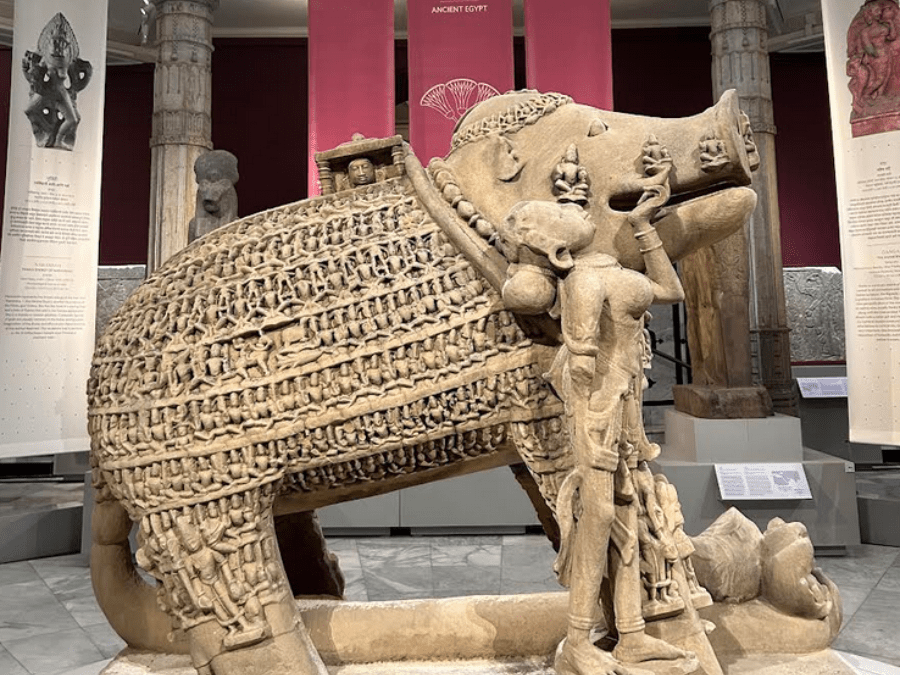

The lotus is regarded as a sign of peace, wealth, purity, and beauty in many civilizations, including India, Egypt, and China. The exhibition’s focus, however, is a magnificent Yajna Varaha sculpture from Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh, which is carefully situated beneath the museum’s huge rotunda. It immediately directs visitors to the exhibition’s centre.

The Varaha avatar of Vishnu portrays all that exists, but it also relates many stories, especially the story of the cosmic yajna (sacrifice) and the myth of the ocean churning. Similarly, the exhibition’s sculptures tell various stories.

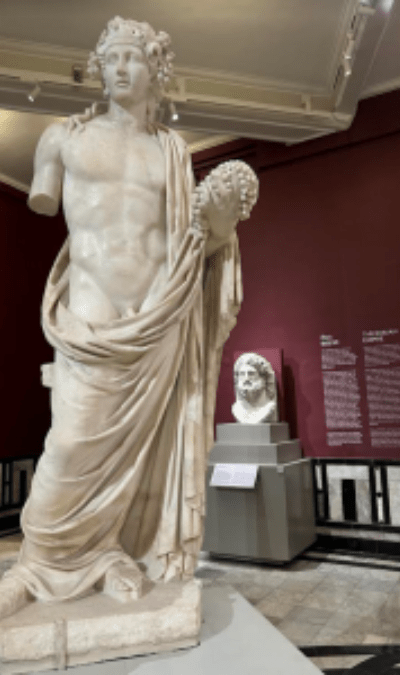

Several symbols from Greek, Roman, and Egyptian mythologies have been cleverly set around the Varaha, forming several strands of interaction between the deities from different cultures. A marble bust of the Greek deity Zeus (Jupiter in Rome) and graceful, naked torsos of Triton, Apollo, and Dionysus demonstrate the beauty of the human body.

A delicate picture of Greek Aphrodite (Roman Venus), the goddess of love and passion, from the Berlin Museum is compared to comparable female forms seen on the Hindu temple’s walls, such as apsaras and yakshinis. The museum has chosen to promote the Didarganj Yakshini as a feminine ideal from ancient India. Even though this renowned icon, dating from the third century BCE and now housed in the Bihar Museum in Patna, is not physically present in the exhibition, its extensive description and photographs convey the concept.

In the following phase, the museum intends to open an ancient world gallery. This entails acquiring objects on long-term loan from partner museums in order to show crucial periods in Indian history in a broader global context and to investigate ancient relationships between India and the rest of the globe.