How To Develop An Academic Argument? Know It All Here

By Kavya Patel | The WFY Magazine | Academics Feature, October 2025 Edition

The Art of Reasoning: How to Develop an Academic Argument

Introduction: Beyond Opinions – The Craft of Thought

Every day, students across the world are asked to “make an argument”. In essays, research papers, debates, and dissertations, the phrase recurs like a drumbeat. Yet, for many, the word ‘argument’ still conjures images of quarrels or confrontations. In academic life, however, an argument is neither a fight nor a slogan; it is the disciplined art of reasoning, grounded in evidence and expressed with clarity.

In an age when information floods every screen and artificial intelligence tools churn out instant summaries, the ability to build an argument, a coherent, reasoned case supported by credible evidence, has become a defining skill of the educated mind. It separates thinkers from followers, learners from repeaters.

From the university classrooms of London and Toronto to the study desks of Delhi and Dubai, academic writing today demands more than the presentation of facts. It requires persuasion. But persuasion in the academic world is not about rhetoric or emotion; it is about logic, structure, and proof.

The DNA of an Argument

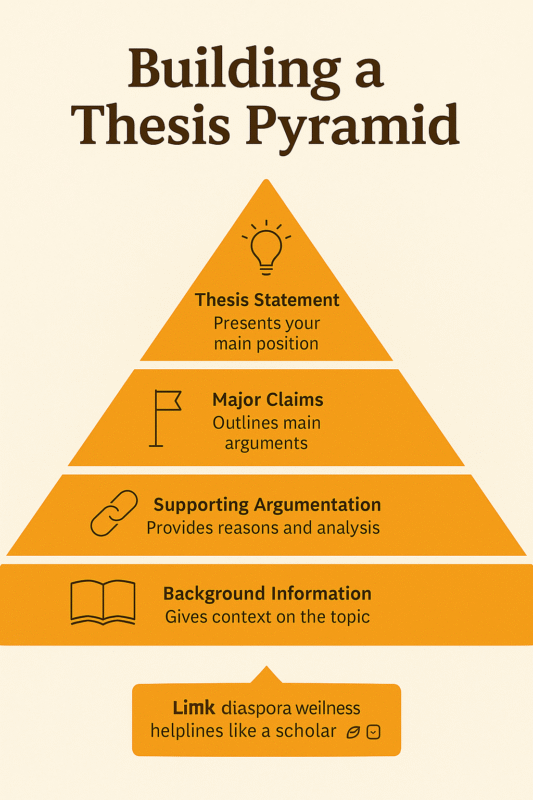

At its simplest, an argument has three essential components:

- A claim – the central idea or assertion one wishes to prove.

- Evidence – the facts, examples, or data that support the claim.

- Reasoning – the explanation that connects evidence to the claim.

These three elements together form what philosopher Stephen Toulmin called the Toulmin Model of argumentation, a structure widely used in academic reasoning and debate. The model adds two more dimensions: warrants (the logical connection between claim and evidence) and counterarguments (the opposing views one must address).

A student may claim, for instance, that “renewable energy is the most sustainable solution to climate change.” The evidence could include data on carbon emissions, cost efficiency, and long-term viability. The reasoning would explain how renewable systems reduce dependence on fossil fuels and lower ecological impact. The argument gains strength when it anticipates objections, for example, the cost of infrastructure or the limitations of technology, and responds logically.

Why Academic Argument Matters in 2025?

In the global academic landscape, where artificial intelligence, deepfakes, and algorithmic misinformation blur the line between truth and noise, the ability to reason critically is no longer just a scholarly virtue; it is a civic necessity.

A 2024 survey by the Times Higher Education World University Rankings revealed that over 70 per cent of employers in Europe and North America now value “critical reasoning and argumentation” more than technical skills in graduates.

In India, the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 emphasised “critical and analytical thinking” as a foundational skill from secondary school onwards.

For the Indian diaspora, whose students dominate global universities, from Oxford and Cambridge to Stanford and NUS, mastering academic argumentation is a gateway to both intellectual credibility and global employability.

Yet many struggle. The challenge lies not in intelligence but in training. Students often know what to think but not how to think. Academic argumentation demands the latter.

From Assertion to Analysis – The Journey of an Argument

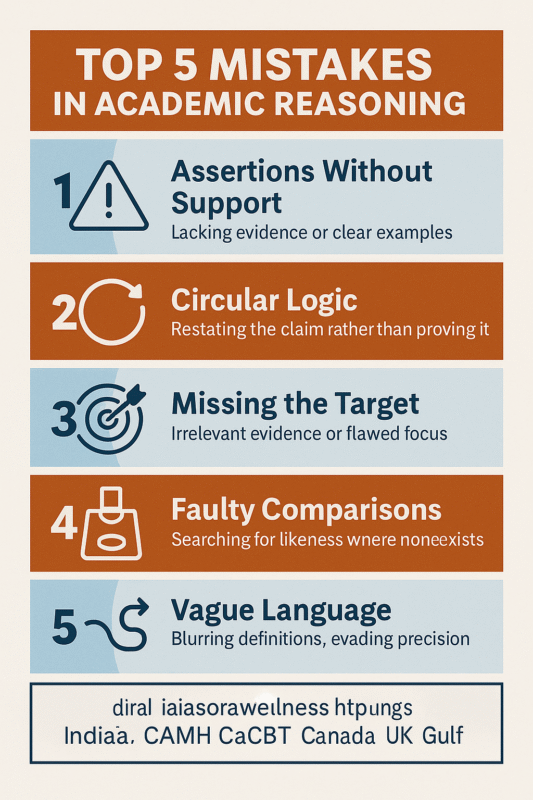

Most early academic writing falters because it confuses assertion with argument.

An assertion states; an argument proves.

Saying “social media harms mental health” is an assertion.

Explaining how and why it harms mental health, and to what extent, with evidence and interpretation, transforms it into an argument.

Good arguments move from claim to complexity. They are never satisfied with a simple yes or no. Instead, they explore how much, how far, under what conditions, and for whom.

For instance, a sociology student may argue that “social media affects adolescent self-esteem.” A deeper academic version would say:

“While social media platforms can enhance social belonging, excessive exposure to curated online identities correlates with lower self-esteem in adolescents, particularly among girls aged 13–17 in urban areas.”

Notice how the revised statement introduces nuance, the hallmark of good argumentation. It balances generalisation with specificity, showing awareness of conditions and context.

Building from the Ground Up – Research and Question

Every argument begins not with an answer, but with a question.

A strong academic argument is born from curiosity. “Why?” “How?” “What if?”

This stage, the research question, shapes everything that follows.

A vague question produces a vague argument. A focused question leads to insight.

Consider these examples:

- Vague: “Is technology good or bad for education?”

- Focused: “How has the introduction of AI-driven tutoring platforms affected learning outcomes among first-generation university students in India?”

The latter directs research, identifies measurable factors, and invites critical evaluation.

Once the question is set, credible sources must be gathered: peer-reviewed journals, government reports, data repositories, and scholarly books. In 2025, with widespread access to digital libraries such as JSTOR, PubMed, and Project MUSE, sourcing credible material is easier than ever.

But discernment is key. The most frequent error among young writers is to fill essays with information instead of evidence. Data without analysis is decoration. Academic argument demands integration, connecting facts to ideas and ideas to interpretation.

The Architecture of Logic

An academic argument is not a collection of points; it is an architecture of reasoning.

Every paragraph should function like a building block:

- The topic sentence introduces a mini-claim.

- The evidence substantiates it.

- The analysis interprets and connects it to the central thesis.

Imagine the structure as a bridge:

- The thesis is the foundation.

- Each paragraph is a plank that carries the reader forward.

- The conclusion is the arrival point, not a repetition but a revelation.

Clarity of organisation enhances persuasiveness. The best arguments follow what scholars call the “hourglass model”: beginning with broad context, narrowing to detailed analysis, and widening again to broader implications.

An academic essay must never feel like a shopping list of quotations. The writer’s voice should guide the narrative, informed, critical, and original.

Evidence – The Heartbeat of Argument

Without evidence, an argument collapses into opinion. The strength of any claim rests on the quality and interpretation of its evidence.

Evidence can take many forms:

- Quantitative data (statistics, surveys, charts)

- Qualitative data (interviews, case studies, observations)

- Theoretical references (concepts, models, frameworks)

- Historical or literary examples (texts, events, analogies)

But evidence alone does not persuade. It must be analysed and explained in the writer’s own reasoning.

A psychology student citing the statistic “40 per cent of adolescents experience online anxiety” must interpret what that number signifies, why it matters, how it relates to their thesis, and what it implies.

The art lies in balance: too little evidence weakens; too much evidence overwhelms. Academic writing is about proportion, not accumulation.

The Role of Counterarguments

An argument without opposition is incomplete.

The strength of academic reasoning lies not in ignoring criticism but in addressing it.

Anticipating counterarguments shows maturity, fairness, and intellectual honesty.

For instance, an economics essay arguing for universal basic income might include objections about inflation or fiscal burden and then respond logically with data or theory.

This process, known as dialectical reasoning, mirrors the Socratic method: truth emerges through dialogue, not monologue.

According to a 2023 Cambridge Writing Study, essays that incorporated balanced counterpoints scored 30 per cent higher on critical analysis than those presenting only one-sided views.

The rule is simple: acknowledge other perspectives before refuting them. It shows that your conclusion was earned, not imposed.

Language and Tone – The Academic Voice

The academic voice is not about complex vocabulary but precise expression.

Avoiding emotional or subjective terms (“I feel”, “obviously”, “everyone knows”) creates distance and objectivity.

However, academic writing today, especially in humanities and social sciences, no longer demands robotic neutrality. A confident “I argue” or “this paper contends” is perfectly acceptable when used judiciously.

British academic conventions favour clarity, concision, and subtlety. Sentences should flow naturally but remain economical.

Transition words such as ‘however’, ‘therefore’, ‘consequently’, ‘nevertheless’, and ‘whereas’ guide the reader logically.

Good argumentation also respects ethos (credibility), pathos (human relevance), and logos (logic), the classical triad of persuasion identified by Aristotle.

A successful academic essay harmonises all three.

Common Fallacies – The Enemies of Reason

Every writer must guard against logical fallacies, the traps that undermine reasoning.

Some of the most common include:

- Hasty Generalisation: drawing a conclusion from insufficient evidence.

- Ad Hominem: attacking the person rather than the idea.

- False Cause: assuming correlation implies causation.

- Appeal to Popularity: assuming something is true because many believe it.

- Straw Man: misrepresenting an opposing argument to refute it easily.

Recognising these fallacies sharpens one’s analytical precision.

In an age of viral misinformation, mastering logical integrity is as vital as writing style.

Data and Digital Literacy – The Modern Academic Toolkit

In 2025, research has moved beyond the library to the digital sphere. Yet with abundance comes danger; not all sources are equal.

A Pew Research Centre report in 2024 found that 62 per cent of university students had unknowingly cited non-academic or commercially biased websites in coursework.

Digital literacy now demands critical verification, evaluating credibility, currency, authorship, and bias before accepting data.

Tools such as Google Scholar, Crossref, and ResearchGate aid citation tracking. Plagiarism detection systems like Turnitin ensure originality.

However, overreliance on AI writing assistants or paraphrasing software can dilute genuine reasoning. The line between aid and automation must be guarded carefully.

True argumentation involves thinking, not just wording. Machines can produce sentences, but they cannot wrestle with ideas.

Cultural and Contextual Awareness

For the global Indian diaspora, academic argumentation carries additional dimensions: cultural context, linguistic nuance, and cross-disciplinary sensitivity.

Indian students, particularly those educated in rote-learning systems, often struggle to express disagreement with authority. Yet in Western academia, challenging ideas is seen as intellectual engagement, not disrespect.

This shift in attitude is critical. Argumentation thrives on questioning, not conformity.

A healthy seminar room is one where disagreement is polite, informed, and evidence-driven.

Moreover, writers must be aware of cultural frames that shape reasoning. What counts as “proof” or “authority” in one culture may differ in another. Integrating both Western analytical rigour and Eastern philosophical depth can enrich global academic discourse.

Diaspora academics today are uniquely positioned to bring this balance.

Academic Integrity – The Moral Foundation

No argument can stand without integrity.

Plagiarism, deliberate or accidental, remains one of the gravest offences in academia. Copying, close paraphrasing, or uncredited use of another’s ideas destroys credibility.

A 2023 study by the Quality Assurance Agency (UK) reported that academic misconduct cases rose by 23 per cent among international students post-pandemic, largely due to unawareness of citation conventions.

To avoid this, every claim must trace its intellectual ancestry. Using citation styles such as APA, MLA, or Harvard is not bureaucracy; it is a gesture of respect to prior thinkers.

Academic honesty builds trust, the invisible currency of scholarship.

From Argument to Contribution

The ultimate purpose of argumentation is not to win but to contribute.

A strong argument expands understanding, reframes questions, or opens new paths of inquiry.

Whether analysing Shakespeare or climate policy, every well-crafted argument adds a drop to the ocean of human knowledge.

This is what distinguishes academic reasoning from casual debate; it aims not to defeat but to deepen.

At postgraduate and doctoral levels, this principle becomes vital. A thesis is essentially a sustained argument supported by evidence across hundreds of pages.

The question “What is your argument?” is the academic equivalent of “Who are you?”

Teaching Argumentation – A New Educational Priority

Recognising its importance, universities are reforming pedagogy to prioritise argumentation.

In India, the University Grants Commission (UGC) introduced Academic Writing and Reasoning modules in 2024 for undergraduate curricula.

In the UK, the Critical Thinking in Context initiative is now part of A-Level reforms.

Data show measurable impact. At the University of British Columbia, students who underwent structured argumentation workshops improved their analytical essay scores by 18 per cent on average.

In Delhi University’s pilot project, the inclusion of debate-based tutorials in humanities courses reduced plagiarism cases by 22 per cent, as students learnt to think independently rather than copy.

The evidence is clear: teaching reasoning is teaching responsibility.

The Emotional Intelligence of Argument

While academic argument appears purely rational, emotional intelligence also plays a role.

Good arguments are not cold; they are humane. They respect diversity, acknowledge uncertainty, and treat readers as partners in inquiry.

Psychologists studying learning behaviour note that students who connect emotionally with their topic produce more coherent arguments. Motivation fuels precision.

A well-crafted argument is therefore both intellectual and moral, guided by empathy as much as logic.

As one Oxford lecturer put it recently, “Argument is not about shouting louder; it is about listening deeper.”

The Future of Thought

In the coming decade, as artificial intelligence accelerates content production, the world will hunger for authenticity.

What will distinguish a true scholar from a machine will not be grammar, but judgement, the ability to weigh, reason, and argue.

Developing an academic argument, then, is not merely a writing skill. It is a life skill. It teaches patience, humility, and intellectual courage.

It teaches us to question, to listen, and to build ideas on the foundation of fairness.

For the Indian diaspora, scattered across continents but bound by curiosity and ambition, mastering this art is a way of shaping not just careers but conversations – conversations that can move classrooms, influence policy, and shape the moral compass of knowledge itself.

So, the next time you are asked to “make an argument”, remember: it is not about winning the debate but about understanding the world, one reason at a time.