Great Romani: The Best of The Indian Migrants

Romani are the first Indians to go to Europe largely from the present day Punjab and nearby areas. Linguistic and genetic evidence suggests that the Roma originated in the northern regions of the Indian subcontinent; in particular, the Rajasthan, Haryana, and Punjab regions of modern-day India. In February 2016, during the International Roma Conference, then Indian Minister of External Affairs, Sushma Swaraj stated that the people of the Roma community were children of India. The conference ended with a recommendation to the government of India to recognize the Roma community spread across 30 countries as a part of the Indian diaspora.

Around 326 BC, the forces of Alexander of Macedon are considered to have transported the first wave of the Roma out of India. This was because they were iron smelters and skilled in making war weapons. The word “Roma” is thought to have originated from the Sanskrit term “doma,” also known as the contemporary “dom” or its variations, which may be found in numerous Indian languages and refers to lower castes involved in a variety of menial tasks and, in some cases, itinerant singing and dancing careers.

According to a 2012 study that analysed around 800,000 genetic variants in 152 Romani people from 13 Romani communities throughout Europe, it concluded that the Roma people fled northern India around 1,500 years ago, and the Roma who currently live in Europe went across the Balkans around 900 years ago.

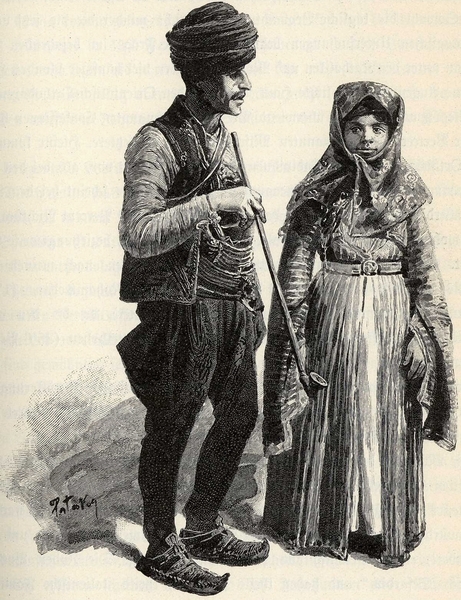

The Roma, also known as the Romani, are a nomadic people that mostly inhabit Europe and America. Anthropologists, historians, and geneticists generally agree that the Roma’s ancestral homeland is northern India. Zigeuner in Germany, Tsiganes or Manus in France, Tatara in Sweden, Gitano in Spain, Tshingan in Turkey and Greece, Gypsy in the UK, etc. are some of the several names used to refer to the Roma. Some of these names carry blatantly racist overtones and are seen as such by the Romani people.

The Roma (Gypsies) originated in the Punjab region of northern India as a nomadic people and entered Europe between the eighth and tenth centuries C.E. They were called “Gypsies” because Europeans mistakenly believed they came from Egypt. This minority is made up of distinct groups called “tribes” or “nations.”

The Roma are an ethnic people who have migrated across Europe for a thousand years. The Roma culture has a rich oral tradition, with an emphasis on family. Often portrayed as exotic and strange, the Roma have faced discrimination and persecution for centuries. Some of the famous personalities of Roma descent are, painter Pablo Picasso, actor-filmmaker Charlie Chaplin, performer Elvis Presley, Hollywood legend Michael Caine, tennis player Ilie Nastase, and actor Yul Brynner.

Since many Roma are hesitant to declare their ethnicity in official national censuses for fear of being harassed or persecuted, the exact number is unknown. The global population of the Roma minority was believed to be around 20 million as of 2016. About 30 nations in West Asia, Europe, America, and Australia are home to the Roma people. With 2.75 million members, Turkey has the largest Roma population. There are thought to be 800,000 people in Brazil and perhaps 1 million in the US. There are significant Roma populations in Romania, Bulgaria, Russia, Slovakia, Hungary, Serbia, Spain, and France.

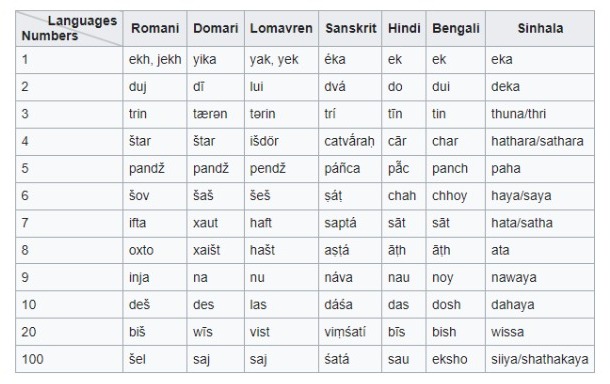

The Romani language is clearly related to those spoken in northern India, and many of the most popular Romani words—including the numerals—are virtually identical to the names they have in contemporary Hindi. Examples include the Romani word for “ek,” which is the same as the Hindi word for “ek,” dui (do), trin (teen), shtaar (chaar), panchi (paanch), sho (chhe), desh (dus), bish (bees), manush (manushya, or man), baal, kaan, and naak, which are the same as the Hindi words for “hair,” “ear,” and “nose”

The Roma and Indian groups share a number of cultural practices, such as the connection of white with mourning, the tradition of mehndi application by Indian brides, the observance of ritual purity rules, and taboos about birth and death. Because a woman giving birth is seen as impure, she must deliver the baby outside of her caravan or tent to prevent contamination. Their close ties to Hindu culture are suggested by the high rate of child marriages and the worship of deities like Shiva, Kali, and Agni.

In popular literature and film, the Roma are portrayed as having unpredictable temperaments and magical or occult abilities, including fortune telling. In addition to the basic misconceptions about them, they are frequently portrayed as robbers or lawbreakers.

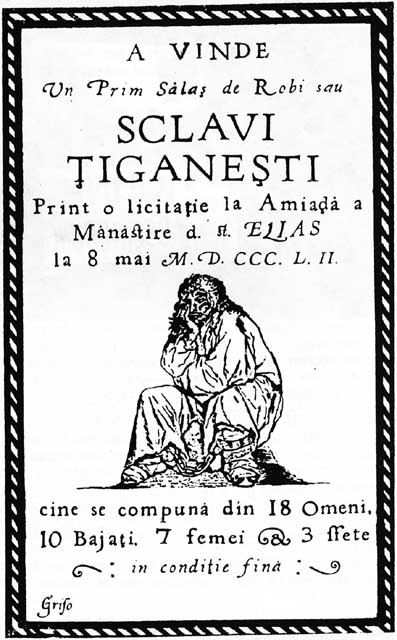

Since the commencement of their immigration to Europe, racism has translated into government persecution. In Germany, Italy, and Portugal, they were sold into slavery or slaughtered; they endured prejudice due to the colour of their skin; and they were blamed for bringing the terrible plague to Europe.

Roma people were sent to concentration camps by the Nazis. A statute enabling the denial of citizenship to Roma was adopted in Turkey in 1934. Roma women were compelled to get sterilization in Czechoslovakia in the 1980s. Even now, there are cases of Roma women having their ears cut off and children being taken away from their parents. The removal of 51 illegal Roma camps by the French government in 2010, caused a stir and warnings of retaliation from the EU.

According to a 2011 survey conducted in 11 European nations, only one out of every two Roma children attended school on an average, and only one out of every three Roma adults held a paid job. Nearly half of the Roma populations in these nations experienced prejudice as a result of their ethnicity, and nearly 90% of them lived below the poverty level.

The majority of Roma belonged to the Sinti and Roma family groupings. Both groups spoke dialects of a common language called Romani, based on Sanskrit (the classical language of India). The term “Roma” has come to include both the Sinti and Roma groupings, though some Roma prefer to be known as “Gypsies.” Some Roma are Christian and some are Muslim, having converted during the course of their migrations through Persia, Asia Minor, and the Balkans.

For centuries, the Roma were scorned and persecuted across Europe. Zigeuner, the German word for gypsy, derives from a Greek root meaning “untouchable.”

Many Roma traditionally worked as craftsmen and were blacksmiths, cobblers, tinsmiths, horse dealers, and toolmakers. Others were performers, such as musicians, circus animal trainers, and dancers. By the 1920s, there were also a number of Romani shopkeepers. Some Roma, such as those employed in the German postal service, were civil servants. The number of truly nomadic Roma was on the decline in many places by the early 1900s, although many so-called sedentary Roma often moved seasonally, depending on their occupations.

In 1939, about 1 to 1.5 million Roma lived in Europe. Roughly half of all European Roma live in Eastern Europe, particularly in the Soviet Union and Romania. Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria also had large Romani communities. In Prewar Germany, there were at most 35,000 Roma, most of whom held German citizenship. In Austria, there were approximately 11,000 Roma. Relatively few Roma lived in Western Europe.

Romani people

The Romani, colloquially known as the Roma, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic itinerants. Most of the Romani people live in Europe, and diaspora populations also live in the Americas.

Ukraine: 47,587–260,000 (0.6%)

Romania: 619,007–1,850,000 (3.29–8.3%)

Spain: 750,000–1,500,000 (1.9–3.7%)

France: 500,000–1,200,000

Moldova: 12,778–107,100 (3.0%)

Montenegro: 5,251–20,000 (3.7%)

North Macedonia: 53,879–197,000 (9.6%)

DNA

Gypsies traveled, taking the DNA and genetic history that they picked up along the way with them. Consequently, it’s not uncommon for a Gypsy individual to get DNA results that reflect a mix that includes South Asian DNA, Middle Eastern DNA, and one or even several European ethnicities.

Surname

You may have Romani, Traveller or Gypsy ancestry if your family tree includes common Romani or Gypsy surnames such as Boss, Boswell, Buckland, Chilcott, Codona, Cooper, Doe, Lee, Gray (or Grey), Harrison, Hearn, Heron, Hodgkins, Holland, Lee, Lovell, Loveridge, Scamp, Smith, Wood and Young.

Many groups use names apparently derived from the Romani word kalo or calo, meaning “black” or “absorbing all light”. This closely resembles words for “black” or “dark” in Indo-Aryan languages (e.g. Sanskrit काल kāla: “black”, “of a dark colour“). Likewise, the name of the Dom or Domba people of North India – to whom the Roma have genetic, cultural and linguistic links – has come to imply “dark-skinned“, in some Indian languages. Hence names such as kale and calé may have originated as an exonym or a euphemism for Roma.

Flag of the Romani people

The Romani flag or flag of the Roma (Romani: O styago le romengo, or O romanko flako) is the international flag of the Romani people. It was approved by the representatives of various Romani communities at the first and second World Romani Congresses (WRC), in 1971 and 1978. The flag consists of a background of blue and green, representing the heavens and earth, respectively; it also contains a 16-spoke red dharmachakra, or cartwheel, in the center. The latter element stands for the itinerant tradition of the Romani people and is also an homage to the flag of India, added to the flag by scholar Weer Rajendra Rishi.

Modern history

Romani began emigrating to North America in colonial times, with small groups recorded in Virginia and French Louisiana. Larger-scale Roma emigration to the United States began in the 1860s, with Romanichal groups from Great Britain. The most significant number immigrated in the early 20th century, mainly from the Vlax group of Kalderash. Many Romani also settled in South America.

During World War II, the Nazis embarked on a systematic genocide of the Romani, a process known in Romani as the Porajmos. Romanies were marked for extermination and sentenced to forced labour and imprisonment in concentration camps. They were often killed on sight, especially by the Einsatzgruppen (paramilitary death squads) on the Eastern Front. The total number of victims has been variously estimated at between 220,000 and 1,500,000.

The Romani people were also persecuted in Nazi puppet states. In the Independent State of Croatia, the Ustaša killed almost the entire Roma population of 25,000. The concentration camp system of Jasenovac, run by the Ustaša militia and the Croat political police, were responsible for the deaths of between 15,000 and 20,000 Roma.

Post-1945

In Czechoslovakia, they were labelled a “socially degraded stratum“, and Romani women were sterilized as part of a state policy to reduce their population. This policy was implemented with large financial incentives, threats of denying future welfare payments, with misinformation, or after administering drugs.

An official inquiry from the Czech Republic, resulting in a report (December 2005), concluded that the Communist authorities had practised an assimilation policy towards Romanis, which “included efforts by social services to control the birth rate in the Romani community. The problem of sexual sterilisation carried out in the Czech Republic, either with improper motivation or illegally, exists,” said the Czech Public Defender of Rights, recommending state compensation for women affected between 1973 and 1991. New cases were revealed up until 2004, in both the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Germany, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland “all have histories of coercive sterilization of minorities and other groups”.

Society, tradition and culture.

Romani society and culture

For centuries, stereotypes and prejudices have had a negative impact on the understanding of Roma culture. Also, because the Roma people live scattered among other populations in many different regions, their ethnic culture has been influenced by interaction with the culture of their surrounding population. Nevertheless, there are some unique and special aspects to Romani culture.

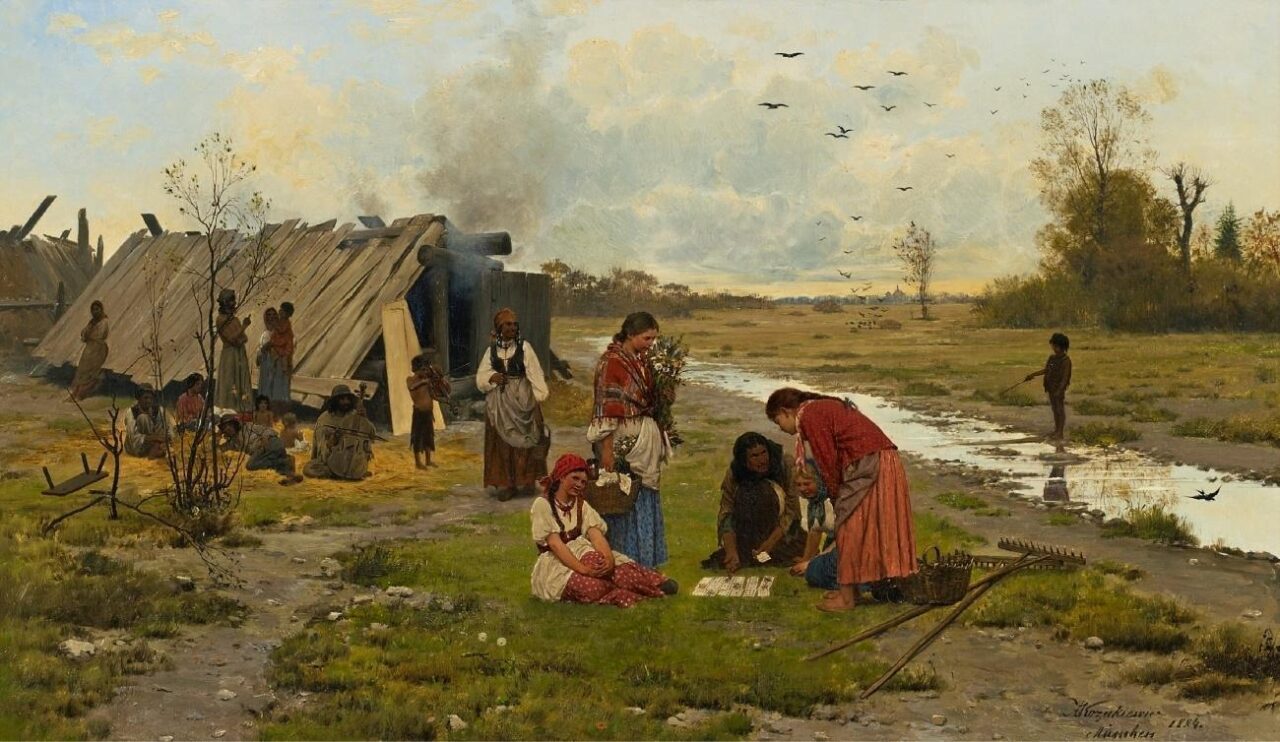

Traditionally, as can be seen on paintings and photos, some Roma men wear shoulder-length hair and a mustache, as well as an earring. Roma women generally have long hair, and Xoraxane Roma women often dye it blonde with henna.

Spiritual beliefs

The Roma do not follow a single faith; rather, they often adopt the predominant religion of the country where they are living, according to Open Society, and describe themselves as “many stars scattered in the sight of God.” Some Roma groups are Catholic, Muslim, Pentecostal, Protestant, Anglican or Baptist.

The Roma live by a complex set of rules that govern things such as cleanliness, purity, respect, honor and justice. These rules are referred to as what is “Rromano.” Rromano means to behave with dignity and respect as a Roma person, according to Open Society. “Rromanipé” is what the Roma refer to as their worldview.

Romani social behaviour is strictly regulated by Indian social customs (“marime” or “marhime”), still respected by most Roma (and by older generations of Sinti). This regulation affects many aspects of life and is applied to actions, people and things: parts of the human body are considered impure: the genital organs (because they produce emissions) and the rest of the lower body. Clothes for the lower body, as well as the clothes of menstruating women, are washed separately. Items used for eating are also washed in a different place. Childbirth is considered impure and must occur outside the dwelling place. The mother is deemed to be impure for forty days after giving birth.

Death is considered impure, and affects the whole family of the dead, who remain impure for a period of time. In contrast to the practice of cremating the dead, Romani dead must be buried. Cremation and burial are both known from the time of the Rigveda, and both are widely practiced in Hinduism today (the general tendency is for Hindus to practice cremation, though some communities in modern-day South India tend to bury their dead). Animals that are considered to be having unclean habits are not eaten by the community.

Language

Though the groups of Roma are varied, they all do speak one language, called Rromanës. Rromanës has roots in Sanskritic languages, and is related to Hindi, Punjabi, Urdu and Bengali, according to RSG. Some Romani words have been borrowed by English speakers, including “pal” (brother) and “lollipop” (from lolo-phabai-cosh, red apple on a stick).

Hierarchy

Traditionally, anywhere from 10 to several hundred extended families form bands, or kumpanias, which travel together in caravans. Smaller alliances, called vitsas, are formed within the bands and are made up of families who are brought together through common ancestry.

Each band is led by a voivode, who is elected for life. This person is their chieftain. A senior woman in the band, called a phuri dai, looks after the welfare of the group’s women and children. In some groups, the elders resolve conflicts and administer punishment, which is based upon the concept of honor. Punishment can mean a loss of reputation and at worst expulsion from the community, according to the RSG.

Family structure

The Roma place great value on close family ties, according to the Rroma Foundation: “Rroma never had a country — neither a kingdom nor a republic — that is, never had an administration enforcing laws or edicts. For Rroma, the basic ‘unit’ is constituted by the family and the lineage.”

Communities typically involve members of the extended family living together. A typical household unit may include the head of the family and his wife, their married sons and daughters-in-law with their children, and unmarried young and adult children.

The traditional Romanies place a high value on the extended family. Virginity is essential in unmarried women. Both men and women often marry young; there has been controversy in several countries over the Romani practice of child marriage. Romani law establishes that the man’s family must pay a bride price to the bride’s parents, but only traditional families still follow it.

Romani typically marry young — often in their teens — and many marriages are arranged. Weddings are typically very elaborate, involving very large and colourful dress for the bride and her many attendants. Though during the courtship phase, girls are encouraged to dress provocatively, sex is something that is not had until after marriage, according to The Learning Channel. Some groups have declared that no girl under 16 and no boy under 17 will be married, according to the BBC.

Once married, the woman joins the husband’s family, where her main job is to tend to her husband’s and her children’s needs and take care of her in-laws. The power structure in the traditional Romani household has at its top the oldest man or grandfather, and men, in general, have more authority than women. Women gain respect and power as they get older. Young wives begin gaining authority once they have children.

Hospitality

Typically, the Roma love opulence. Romani culture emphasizes the display of wealth and prosperity, according to the Romani Project. Roma women tend to wear gold jewellery and headdresses decorated with coins. Homes will often have displays of religious icons, with fresh flowers and gold and silver ornaments. These displays are considered honourable and a token of good fortune.

Sharing one’s success is also considered honourable, and hosts will make a display of hospitality by offering food and gifts. Generosity is seen as an investment in the network of social relations that a family may need to rely on in troubled times.

The Roma today

While there are still traveling bands, most use cars and RVs to move from place to place rather than the horses and wagons of the past.

Today, most Roma have settled into houses and apartments and are not readily distinguishable. Because of continued discrimination, many do not publicly acknowledge their roots and only reveal themselves to other Roma.

While there is not a physical country affiliated with the Romani people, the International Romani Union was officially established in 1977. In 2000, The 5th World Romany Congress in 2000 officially declared Romani a non-territorial nation.

During the Decade of Roma Inclusion (2005-2015), 12 European countries made a commitment to eliminate discrimination against the Roma. The effort focused on education, employment, health and housing, as well as core issues of poverty, discrimination, and gender mainstreaming. However, according to the RSG, despite the initiative, Roma continue to face widespread discrimination.

According to a report by the Council of Europe’s commissioner for human rights, “there is a shameful lack of implementation concerning the human rights of Roma … In many countries hate speech, harassment and violence against Roma are commonplace.”

April 8 is International Day of the Roma, a day to raise awareness of the issues facing the Roma community and celebrate the Romani culture.

I hope the world gives Roma, its much required due and acknowledge them appropriately. Check out the famous Roma below, Cheers!

FAMOUS CELEBRITIES OF ROMANI ORIGIN

- Michael Caine (1933)

- Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977)

- Yul Brynner (1920-1985)

- Elvis Prisley (1935-1977)

- Bob Hoskins (1942-2014)

- Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

- Rita Hayworth (1918-1987)

Politicians and Activists:

Juscelino Kubitschek – Brazilian president. His mother was of Czech Roma descent.

Damian Draghici – (born 1970) Humanitarian, Civil Society Supporter, Ambassador for European Year of Equal Opportunities for All, musician, Romania

Rajko Djuric – (born 1947) Serbian writer and academic, leader of Roma Union of Serbia

Alfonso Mejia-Arias – musician, writer and politician, Mexico

Ian Hancock – Romani scholar and activist, born in UK, living in USA, Professor at the University of Texas, (I highly recommend his book about the Romani ”WE ARE THE ‘ROMANI PEOPLE” first published 2002, my words Laurie.)

Lívia Járóka – Hungarian Member of the European Parliament

Mădălin Voicu – (born 1952) Romanian politician. His father, Ion Voicu, is Romani

Ştefan Răzvan – (? – 1595) Prince of Moldavia, Ruled Moldavia for four months. (Romani father)

Nicolae Păun – Romanian politician

Ágnes Osztolykán – Hungarian politician

Juan de Dios Ramírez Heredia – Ex-member of the European Parliament, founder of the Romani Union, Spain

Viktória Mohácsi – (born 1975) Hungarian Member of the European Parliament

Ronald Lee – (born 1934, in Montreal), Canadian Romani novelist, activist and U.N. delegate

Romani Rose – German Sinto activist

Dávid Daróczi – (1972–2010) Government Spokesperson of the Republic of Hungary

Rudolf Sarközi – chairman of the Austrian Romani association Kulturverein.

Sani Rifati – Serbian activist

Ali Krasniqi – Albanian writer and activist

Bajram Haliti – Kosovar activist

Carlos Miguel – Portuguese minister and mayor

Idália Serrão – Portuguese secretary of state and MP

Juscelino Kubitschek – 21st President of Brazil

Washington Luís – 13th President of Brazil

Alba Flores – Spanish actress

Ceija Stojka – Austrian artist and writer

Constantin S. Nicolăescu-Plopșor – Romanian historian, archeologist, anthropologist and writer

Delia Grigore – Romanian writer

Katarina Taikon – Swedish actress

Marcel Courthiade – French linguist

Milena Hübschmannová – Czech professor

Paul Polansky – American writer

Saša Barbul – Serbian actor and film director

Football players

Pierre-Yves André – French (Retired)

Aljoša Asanović – Croatian (Retired)

Richard Carpenter – English (Retired)

Freddy Eastwood – Welsh (Free Agent)

Arturo Garcia, Arzu – Spanish (Free Agent)

André-Pierre Gignac – French (Olympique Marseille)

Dani Güiza – Spanish (Getafe)

Raby Howell – English (Retired)

José Mari – Spanish (Xerez CD)

Petre Marin – Romanian (Retired)

Gigi Meroni – Italian (Retired)

Jesús Navas – Spanish (Sevilla FC)

Bănel Nicoliţă – Romanian (AS Saint-Etienne)

Marian Ognyanov – Bulgarian (Botev Plovdiv)

Christos Patsatzoglou – Greek (PAS Giannina F.C.)

Ricardo Quaresma – Portuguese (Beşiktaş)

José Antonio Reyes – Spanish (Sevilla FC)

Tommaso Vailatti – Italian (Retired)

David Vairelles – French (FC Gueugnon)

Tony Vairelles – French (FC Gueugnon)

Rafael van der Vaart – Dutch (Hamburger SV)

Authors and Writers

Veijo Baltzar – Finnish writer

Rajko Djuric – (born 1947) Serbian writer & activist

Caren Gussoff – American writer. Claims “Romani and mixed heritages”.

Delia Grigore – (born 1972) Romanian writer, academic and activist

Ronald Lee – Canadian writer, Romani activist and lecturer at the University of Toronto.[2]

Matéo Maximoff – French writer

Louise Doughty – British writer

John Bunyan – Christian author

Lafcadio Hearn – Irish writer

Charlie Smith – poet.

Baja Saitovic Lukin – poet

Ceija Stojka – (born 1933) Austrian author and painter

Katarina Taikon – (born 1932) Swedish children’s writer

Bronisława Wajs – (1908–1987) AKA “Papusza”, Polish poet and singer.

David Morley – English

Elena Lacková – Slovak

Hillary Monahan – American

Mariella Mehr – Swiss

Menyhért Lakatos – Hungarian

Muharem Serbezovski – Macedonian

Nina Dudarova – Russian

Rajko Đurić – Serbian

Hedina Tahirović-Sijerčić – Bosnian

Various

Kerope Patkanov – scientist

Rodney “Gipsy” Smith – (1860–1947), British evangelist

August Krogh – scientist, Nobel prize winner

Sofia Kovalevskaya – Major Russian female mathematician of 1/4 Romani descent[9]

Jimmy Marks – litigant in a lawsuit against the city of Spokane, Washington

Settela Steinbach – Holocaust victim

Ceferino Giménez Malla – a Spanish beatified Catholic catechist

Juana Martín Manzano – Spanish fashion designer

Didem – Turkish belly dancer

Timofey Prokofiev – Soviet marine infantryman, Hero of the Soviet Union

Athletes

Florin Lambagiu – Romanian

Nieky Holzken – Dutch

Professional Wrestlers

Gigi Dolin – American

Footballers

André-Pierre Gignac – French

Andrea Pirlo – Italian

Artur Quaresma – Portuguese

Bănel Nicoliță – Romanian[

Carlos Martins – Portuguese

Carlos Muñoz Cobo – Spanish

Christos Patsatzoglou – Greek

Dejan Savićević – Montenegrin

Diego Rodríguez – Spanish

Dragoslav Šekularac – Serbian

Eric Cantona – French

Freddy Eastwood – Welsh

Georgi Ivanov – Gonzo – Bulgarian

Gigi Meroni – Italian

István Pisont – Hungarian

János Farkas – Hungarian

José Mari – Spanish

Marius Lăcătuș – Romanian

Milan Baroš – Czech

Quique Sánchez Flores – Spanish

Rab Howell – English

Ricardo Quaresma – Portuguese

Telmo Zarra – Spanish

Zlatan Ibrahimović – Swedish

Zvonimir Boban – Croatian

Cinema and Theatre

Alba Flores – Spanish actress

Bob Hoskins – English actor

Charlie Chaplin – English comic actor[25]

Jesús Castro– Spanish actor

Joaquín Cortés – Spanish ballet and flamenco dancer

Leonor Teles – Portuguese film director

Manoush – French actress

Sandro de América – Argentine actor

Ștefan Bănică Sr. – Romanian actor

Tony Gatlif – French film maker of Algerian Kabyle and Spanish Roma origin.

Yul Brynner – Russian actor and president honour of the Unión Romaní

Leonard Whiting – British actor of English and Irish ancestry who claims to “also have some Gypsy blood”.

Marcia Nicole Lakatos known as Manoush – Dutch-German actress. Her mother is of Manouche origin.

Soledad Miranda – Andalusian Flamenco Dancer and later Horror Film Actress from Seville, mother was Gitana

Nikolai Slichenko – Russian actor

Angel Dark – Slovak pornstar

Moira Orfei – Italian actress

Artists

Antonio Solario – Italian artist

Helios Gómez – Spanish artist, writer and poet

Serge Poliakoff (1906–1969) – painter

Otto Mueller – painter and printmaker, Sinti mother

Micaela Flores Amaya, La Chunga, Flamenco dancer and painter

Joe Machine, (1973) British Stuckist painter

Damian Le Bas, English artist

Delaine Le Bas, English artist

La Chunga, Spanish painter

Boxers

Dawid Kostecki – Polish light heavyweight boxer of Romani decent

Ivailo Marinov – also known as Ismail Mustafov, Ismail Huseinov or Ivailo Khristov) is a Rom Bulgarian boxer, who won the bronze medal at the 1980 Summer Olympics in light flyweight, and the gold medal in the same category at the 1988 Summer Olympics

Serafim Todorov – was a Bulgarian/Georgian boxer at the 1996 Summer Olympics who won a silver medal. He is the last boxer to ever defeat the highly regarded Floyd Mayweather Jr.

Boris Georgiev – is an amateur boxer from Bulgaria who won a bronze medal at the 2004 Summer Olympics in the Light Welterweight class

Jem Mace – Bareknuckle Boxing Champion, Father of Modern Boxing; called “The Gypsy,” but denies Romani ancestry in his autobiography

Johann Wilhelm Trollmann – German light-heavyweight boxer killed during the Porajmos

Silvio Branco – Italian light heavyweight Boxing Champion

Michele di Rocco – Italian Light Welterweight Boxing Champion

Faustino Reyes – Spanish Boxing he won the silver medal in the featherweight division (– 57 kg), 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona

Billy Joe Saunders – British Boxing, represented Great Britain in the 2008 Olympics

Norbert Kalucza – Hungarian Boxing

Jakob Bamberger – German amateur boxer, twice the German Vice-flyweight champion, Olympic selection in 1936, in the years 1970/80 activist in Sinti civil rights movement

Luke Tyson Fury – British professional boxer who fights in the heavyweight division

Dorel Simion – Romanian

Marian Simion – Romanian

Samuel Carmona Heredia – Spanish

Zoltan Lunka – Hungarian

Kickboxers

Albert Kraus – Dutch

References

- ^Lewis, M. Paul, ed. (2009). “Ethnologue: Languages of the World” (online) (16th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL. Retrieved 15 September 2010. Ian Hancock‘s 1987 estimate for ‘all Gypsies in the world’ was 6 to 11 million.

- ^ “EU demands action to tackle Roma poverty”. BBC News. 5 April 2011.

- ^ “The Roma”. Nationalia. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ “Rom”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 September 2010. … estimates of the total world Roma population range from two million to five million.

- ^ Smith, J. (2008). The marginalization of shadow minorities (Roma) and its impact on opportunities (Doctoral dissertation, Purdue University).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kayla Webley (13 October 2010). “Hounded in Europe, Roma in the U.S. Keep a Low Profile”. Time. Retrieved 3 October 2015. Today, estimates put the number of Roma in the U.S. at about one million.

- ^ “Falta de políticas públicas para ciganos é desafio para o governo” [Lack of public policy for Romani is a challenge for the administration] (in Portuguese). R7. 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012. The Special Secretariat for the Promotion of Racial Equality estimates the number of “ciganos” (Romanis) in Brazil at 800,000 (2011). The 2010 IBGE Brazilian National Census encountered Romani camps in 291 of Brazil’s 5,565 municipalities.

- ^ “Roma integration in Spain”. European Commission. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s “Roma and Travellers Team. Tools and Texts of Reference. Estimates on Roma population in European countries (excel spreadsheet)”. rm.coe.int Council of Europe Roma and Travellers Division.

- ^ “Estimated by the Society for Threatened Peoples”. Society for Threatened Peoples. 17 May 2007. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021.

- ^ “The Situation of Roma in Spain” (PDF). Open Society Institute. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2010. The Spanish government estimates the number of Gitanos to be a maximum of 650,000.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Diagnóstico social de la comunidad gitana en España : Un análisis contrastado de la Encuesta del CIS a Hogares de Población Gitana 2007” (PDF). mscbs.gob.es. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019. Tabla 1. La comunidad gitana de España en el contexto de la población romaní de la Unión Europea. Población Romaní: 750.000 […] Por 100 habitantes: 1.87% […] se podrían llegar a barajar cifras […] de 1.100.000 personas

- ^ “Roma integration in Romania”. European Commission. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ 2011 census data, based on table 7 Population by ethnicity, gives a total of 621,573 Roma in Romania. This figure is disputed by other sources, because at the local level, many Roma declare a different ethnicity (mostly Romanian, but also Hungarian in Transylvania and Turkish in Dobruja). Many are not recorded at all, since they do not have ID cards [1]. International sources give higher figures than the official census(UNDP’s Regional Bureau for Europe Archived 7 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine, World Bank, International Association for Official Statistics Archived 26 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ “Rezultatele finale ale Recensământului din 2011 – Tab8. Populația stabilă după etnie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune” (in Romanian). National Institute of Statistics (Romania). 5 July 2013. Archived from the original (XLS) on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2013. However, some organizations claim that there are many more Romanis in Romania.

- ^ Schleifer, Yigal (22 July 2005). “Roma rights organizations work to ease prejudice in Turkey”. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ “Türkiye’deki Kürtlerin sayısı!” [The number of Kurds in Turkey!] (in Turkish). 6 June 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ “Türkiye’deki Çingene nüfusu tam bilinmiyor. 2, hatta 5 milyon gibi rakamlar dolaşıyor Çingenelerin arasında”. Hurriyet (in Turkish). TR. 8 May 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ “Situation of Roma in France at crisis proportions”. EurActiv Network. 7 December 2005. Retrieved 21 October 2015. According to the report, the settled Gypsy population in France is officially estimated at around 500,000, although other estimates say that the actual figure is much closer to 1.2 million.

- ^ Gorce, Bernard (22 July 2010). “Roms, gens du voyage, deux réalités différentes”. La Croix. Retrieved 21 October 2016. [Manual Trans.] The ban prevents statistics on ethnicity to give a precise figure of French Roma, but we often quote the number 350,000. For travellers, the administration counted 160,000 circulation titles in 2006 issued to people aged 16 to 80 years. Among the travellers, some have chosen to buy a family plot where they dock their caravans around a local section (authorized since the Besson Act of 1990).

- ^ Население по местоживеене, възраст и етническа група [Population by place of residence, age and ethnic group]. Bulgarian National Statistical Institute (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2015. Self declared

- ^ “Roma Integration – 2014 Commission Assessment: Questions and Answers” (Press release). Brussels: European Commission. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2016. EU and Council of Europe estimates

- ^ Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 – 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus – 12. Ethnic data] (PDF). Hungarian Central Statistical Office (in Hungarian). Budapest. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ János, Pénzes; Patrik, Tátrai; Zoltán, Pásztor István (2018). “A roma népesség területi megoszlásának változása Magyarországon az elmúlt évtizedekben” [Changes in the Spatial Distribution of the Roma Population in Hungary During the Last Decades] (PDF). Területi Statisztika (in Hungarian). 58 (1): 3–26. doi:10.15196/TS580101 (inactive 28 February 2022).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Marsh, Hazel. “The Roma Gypsies of Colombia”. latinolife.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ “Emerging Romani Voices from Latin America”. European Roma Rights Centre. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ “The History and Origin of the Roma”. Romove.radio.cz. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Green, Peter S. (5 August 2001). “British Immigration Aides Accused of Bias by Gypsies”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ “Roma integration in the United Kingdom”. European Commission – European Commission.

- ^ “RME”, Ethnologue

- ^ Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова 2011. у Републици Србији: Национална припадност [Census of population. Households and apartments in 2011 in the Republic of Serbia: Ethnicity] (PDF) (in Serbian). State Statistical Service of the Republic of Serbia. 29 November 2012. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ “Serbia: Country Profile 2011–2012” (PDF). European Roma Rights Centre. p. 7. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ “Giornata Internazionale dei rom e sinti: presentato il Rapporto Annuale 2014 (PDF)” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ “Premier Tsipras Hosts Roma Delegation for International Romani Day”. greekreporter – place. Nick Kampouris. 9 April 2019.

- ^ “Greece NGO”. Greek Helsinki Monitor. LV: Minelres.

- ^ “Roma in Deutschland”, Regionale Dynamik, Berlin-Institut für Bevölkerung und Entwicklung, archived from the original on 29 April 2017, retrieved 21 February 2013

- ^ “Roma integration in Slovakia”. European Commission – European Commission.

- ^ “Population and Housing Census. Resident population by nationality” (PDF). SK: Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2007.

- ^ “Po deviatich rokoch spočítali Rómov, na Slovensku ich žije viac ako 400-tisíc”. SME (in Slovak). SK: SITA. 25 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ “Gypsy”. www.iranian.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2017.

- ^ “GYPSY i. Gypsies of Persia”. Encyclopædia Iranica. 12 December 2002.

- ^ “The 2002-census reported 53,879 Roma and 3,843 ‘Egyptians'”. Republic of Macedonia, State Statistical Office. Archived from the original on 21 June 2004. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ “Sametingen. Information about minorities in Sweden”, Minoritet (in Swedish), IMCMS, archived from the original on 26 March 2017, retrieved 30 March 2013

- ^ Всеукраїнський перепис населення ‘2001: Розподіл населення за національністю та рідною мовою [Ukrainian Census, 2001: Distribution of population by nationality and mother tongue] (in Ukrainian). UA: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. 2003. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Roma /Gypsies: A European Minority, Minority Rights Group International

- ^ Kenrick, Donald (2007). Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies) (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-8108-6440-5.

- ^ “Poland – Gypsies”. Country studies. US. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ “Population by Ethnicity – Delailed Classification, 2011 Census”. Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ Emilio Godoy (12 October 2010). “Gypsies, or How to Be Invisible in Mexico”. Inter Press Service. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Hazel Marsh. “The Roma Gypsies of Latin America”. www.latinolife.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ 2004 census

- ^ “Suomen romanit – Finitiko romaseele” (PDF). Government of Finland. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ 1991 census

- ^ “presentacion-grupos-etnicos-poblacion-gitana-rrom-2019” (PDF). dane.gov.co.

- ^ “Albanian census 2011”. instat.gov.al. Archived from the original (XLS) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ “Republic of Belarus, 2009 Census: Population by Ethnicity and Native Language” (PDF) (in Russian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ “Roma in Canada fact sheet” (PDF). home.cogeco.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007.

- ^ Statistics Canada (8 May 2013). “2011 National Household Survey: Data tables”. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ “Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011” (PDF). 12 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ “Sčítání lidu, domů a bytů”. czso.cz.

- ^ “Roma integration in the Czech Republic”. European Commission – European Commission.

- ^ Yvonne Slee. “A History of Australian Romanies, now and then”. Now and Then. Australia: Open ABC. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Gall, Timothy L, ed. (1998), Worldmark Encyclopedia of Culture & Daily Life, vol. 4. Europe, Cleveland, OH: Eastword, pp. 316, 318, ‘Religion: An underlay of Hinduism with an overlay of either Christianity or Islam (host country religion)’; Roma religious beliefs are rooted in Hinduism. Roma believe in a universal balance, called kuntari… Despite a 1,000-year separation from India, Roma still practice ‘shaktism’, the worship of a god through his female consort…

- ^ Jump up to:a b Vishvapani (29 November 2011). “Hungary’s Gypsy Buddhists & Religious Discrimination”. www.wiseattention.org. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bhalesain, Pravin (2011). “Gypsies embracing Buddhism:A step forward for Building a Harmonious Society in Europe” (PDF). Undv.org/Vesak2011/Panel2. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Gaster, Moses (1911). “Gipsies” . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–43.

- ^ Randall, Kay. “What’s in a Name? Professor take on roles of Romani activist and spokesperson to improve plight of their ethnic group”. Archived from the original on 5 February 2005. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Pickering (2010). “The Romani” (PDF). Northern Michigan University. p. 1. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Bambauer, Nikki (2 August 2018). “The Plight of the Romani People-Europe’s Most Persecuted Minority”. JFCS Holocaust Center. The Romani people are frequently referred to as “gypsies,” but many of them consider this exonym a derogatory term.

- ^ “‘Spain’s gypsies are more invisible than ever’ – The Local”. www.thelocal.es. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ “Revista USP 117 | Texto: A construção das identidades ciganas no Brasil” (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Hancock 2002, p. xx: ‘While a nine century removal from India has diluted Indian biological connection to the extent that for some Romani groups, it may be hardly representative today, Sarren (1976:72) concluded that we still remain together, genetically, Asian rather than European’

- ^ K. Meira Goldberg; Ninotchka Devorah Bennahum; Michelle Heffner Hayes (2015). Flamenco on the Global Stage: Historical, Critical and Theoretical Perspectives. McFarland. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7864-9470-5. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Rough Guides. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Kenrick, Donald (5 July 2007). Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies) (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. xxxvii. ISBN 978-0-8108-6440-5. The Gypsies, or Romanies, are an ethnic group that arrived in Europe around the 14th century. Scholars argue about when and how they left India, but it is generally accepted that they did emigrate from northern India some time between the sixth and 11th centuries, then crossed the Middle East and came into Europe.

- ^ Corrêa Teixeira, Rodrigo. “A história dos ciganos no Brasil” (PDF). Dhnet.org.br. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ Sutherland 1986.

- ^ Matras 2002, p. 239.

- ^ “Romani” (PDF). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Oxford: Elsevier. p. 1. Retrieved 30 August 2009. In some regions of Europe, especially the western margins (Britain, the Iberian peninsula), Romani-speaking communities have given up their language in favor of the majority language, but have retained Romani-derived vocabulary as an in-group code. Such codes, for instance Angloromani (Britain), Caló (Spain), or Rommani (Scandinavia) are usually referred to as Para-Romani varieties.

- ^ “Roma integration in the EU”. European Commission. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ “Compilation of population estimates”. Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 22 June 2007.

- ^ “Roma ghettos in the heart of the EU”. El País. 6 September 2019.

- ^ “There are Gypsies in America? Where?”, My big, fat American Gypsy wedding, TLC, 17 April 2012

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hübshmanová 2003.

- ^ Horvátová, Jana (2002). Kapitoly z dějin Romů (PDF) (in Czech). Praha: Lidové noviny. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2005. Mnohočetnost romských skupin je patrně pozůstatkem diferenciace Romů do původních indických kast a podkast. [The multitude of Roma groups is apparently a relic of Roma differentiation to Indian castes and subcastes.]

- ^ N. Rai et al., 2012, “The Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup H1a1a-M82 Reveals the Likely Indian Origin of the European Romani Populations” (23 September 2016)

- ^ Isabel Fonseca, Bury Me Standing: The Gypsies and their Journey, Random House, p. 100.

- ^ New Ethnic Identities in the Balkans: The Case of the Egyptians (PDF), RS: NI, 2001

- ^ Ian Hancock (2010). Danger! Educated Gypsy: Selected Essays. Univ of Hertfordshire Press. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-1-907396-30-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Jurová, Anna (2003). Vaščka, Michal; Jurásková, Martina; Nicholson, Tom (eds.). “From Leaving The Homeland to the First Assimilation Measures” (PDF). Čačipen Pal O Roma – A Global Report on Roma in Slovakia. Slovakia: 17. Retrieved 7 September 2013. the Sinti lived in German territory, the Manusha in France, the Romanitsel in England, the Kale in Spain and Portugal, and the Kaale in Finland.

- ^ “RomArchive”. www.romarchive.eu. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ “Romani language and alphabet”. Omniglot. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Crowe, David (1995). A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-349-60671-9.

- ^ Dicționarul etimologic român (in Romanian), quoted in DEX-online (see lemma rudár, rudári, s.m. followed by both definitions: gold-miner & wood crafter)

- ^ Sztaki, HU

- ^ Dex online, RO

- ^ “Vlax Romani: Churari (Speech variety #16036)”. Global recordings. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Research Directorate (2001). “Romania: Traditional Roma name for the various Roma clans and description of their traditional occupations; whether these occupations still exist today; distinguishing characteristics of the clans”. Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Boyle, Paul; Halfacree, Keith H.; Robinson, Vaughan (2014), Exploring Contemporary Migration, ISBN 978-1-317-89086-7

- ^ Jurová, Anna (2003). Vaščka, Michal; Jurásková, Martina; Nicholson, Tom (eds.). “From Leaving The Homeland to the First Assimilation Measures” (PDF). Čačipen Pal O Roma – A Global Report on Roma in Slovakia. Slovak Republic: 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013. The word “manush” is also included in all dialects of Romany. It means man, while “Manusha” equals people. This word has the same form and meaning in Sanskrit as well, and is almost identical in other Indian languages.

- ^Gypsy Studies – Cigány Tanulmányok (PDF), HU: Forraykatalin

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Kalaydjieva, Luba; Gresham, David; Calafell, Francesc (2 April 2001). “Genetic studies of the Roma (Gypsies): A Review”. BMC Medical Genetics. 2 (5): 5. doi:10.1186/1471-2350-2-5. PMC 31389. PMID 11299048.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Mendizabal, Isabel; Lao, Oscar; Marigorta, Urko M.; Wollstein, Andreas; Gusmão, Leonor; Ferak, Vladimir; Ioana, Mihai; Jordanova, Albena; Kaneva, Radka; Kouvatsi, Anastasia; Kučinskas, Vaidutis; Makukh, Halyna; Metspalu, Andres; Netea, Mihai G.; de Pablo, Rosario; Pamjav, Horolma; Radojkovic, Dragica; Rolleston, Sarah J.H.; Sertic, Jadranka; Macek, Milan; Comas, David; Kayser, Manfred (December 2012). “Reconstructing the Population History of European Romani from Genome-wide Data”. Current Biology. 22 (24): 2342–2349. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.039. PMID 23219723.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Sindya N. Bhanoo (11 December 2012). “Genomic Study Traces Roma to Northern India”. The New York Times.

- ^ “Today, estimates put the number of Roma in the U.S. at about one million.”

- ^ “European effort spotlights plight of the Roma”, USA Today, 1 February 2005

- ^ Chiriac, Marian (29 September 2004). “It Now Suits the EU to Help the Roma”. Other-news.info. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Pan, Christoph; Pfeil, Beate Sibylle (2003). National Minorities in Europe: Handbook. Braumüller. p. 27f. ISBN 978-3-7003-1443-1.

- ^ Liégois, Jean-Pierre (2007), Roms en Europe, Éditions du Conseil de l’Europe

- ^ “Roma Travellers Statistics” at the Wayback Machine (archived 6 October 2009), Council of Europe, compilation of population estimates. Archived from the original, 6 October 2009.

- ^ Hancock 2001, p. 2.

- ^ Matras 2002, p. 5.

- ^ Dosoftei, Alin (24 December 2007). “Names of the Romani People”. Desicritics. Archived from the original on 7 May 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ^ Bessonov, N; Demeter, N, Ethnic groups of Gypsies, RU: Zigane, archived from the original on 29 April 2007

- ^ Current Biology.

- ^ Hübschmannová, Milena (2002). “Origin of Roma”. RomBase. Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ Matras 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Digard, Jean-Pierre. “GYPSY i. Gypies of Persia”. Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Šebková, Hana; Žlnayová, Edita (1998), Nástin mluvnice slovenské romštiny (pro pedagogické účely) (PDF), Ústí nad Labem: Pedagogická fakulta Univerzity J. E. Purkyně v Ústí nad Labem, p. 4, ISBN 978-80-7044-205-0, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016

- ^ Matras 2002, p. 48.

- ^ “What is Domari?”. University of Manchester. Romani Linguistics and Romani Language Projects. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ “On romani origins and identity”. Radoc. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Romani” (PDF). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Oxford: Elsevier. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ Hancock, Ian (2007). “On Romani Origins and Identity”. RADOC.net. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011.

- ^ “5 Intriguing Facts About the Roma”. Live Science. 23 October 2013.

- ^ N Rai; G Chaubey; R Tamang; A K Pathak; V K Singh; et al. (2012), “The Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup H1a1a-M82 Reveals the Likely Indian Origin of the European Romani Populations”, PLOS ONE, 7 (11): e48477, Bibcode:2012PLoSO…748477R, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048477, PMC 3509117, PMID 23209554

- ^ Kalaydjieva, Luba; Calafell, Francesc; Jobling, Mark A; Angelicheva, Dora; de Knijff, Peter; Rosser, Zoe H; Hurles, Matthew; Underhill, Peter; Tournev, Ivailo; Marushiakova, Elena; Popov, Vesselin (2011), “Patterns of inter- and intra-group genetic diversity in the Vlax Roma as revealed by Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA lineages” (PDF), European Journal of Human Genetics, 9 (2): 97–104, doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200597, PMID 11313742, S2CID 21432405, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2014

- ^ Bianco, Erica; Laval, Guillaume; Font-Porterias, Neus; García-Fernández, Carla; Dobon, Begoña; Sabido-Vera, Rubén; Sukarova Stefanovska, Emilija; Kučinskas, Vaidutis; Makukh, Halyna; Pamjav, Horolma; Quintana-Murci, Lluis; Netea, Mihai G.; Bertranpetit, Jaume; Calafell, Francesc; Comas, David (2020). “Recent Common Origin, Reduced Population Size, and Marked Admixture Have Shaped European Roma Genomes”. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 37 (11): 3175–3187. doi:10.1093/molbev/msaa156. PMID 32589725.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gresham, D; Morar, B; Underhill, PA; Passarino, G; Lin, AA; Wise, C; Angelicheva, D; Calafell, F; Oefner, PJ; Shen, Peidong; Tournev, Ivailo; De Pablo, Rosario; Kuĉinskas, Vaidutis; Perez-Lezaun, Anna; Marushiakova, Elena; Popov, Vesselin; Kalaydjieva, Luba (2001). “Origins and Divergence of the Roma (Gypsies)”. American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (6): 1314–31. doi:10.1086/324681. PMC 1235543. PMID 11704928.

- ^ Morar, Bharti; Gresham, David; Angelicheva, Dora; Tournev, Ivailo; Gooding, Rebecca; Guergueltcheva, Velina; Schmidt, Carolin; Abicht, Angela; Lochmüller, Hanns; Tordai, Attila; Kalmár, Lajos; Nagy, Melinda; Karcagi, Veronika; Jeanpierre, Marc; Herczegfalvi, Agnes; Beeson, David; Venkataraman, Viswanathan; Warwick Carter, Kim; Reeve, Jeff; de Pablo, Rosario; Kučinskas, Vaidutis; Kalaydjieva, Luba (October 2004). “Mutation History of the Roma/Gypsies”. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (4): 596–609. doi:10.1086/424759. PMC 1182047. PMID 15322984.

- ^ Pericic, M; Lauc, LB; Klari, IM; et al. (October 2005). “High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces major episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic populations”. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22 (10): 1964–75. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185. PMID 15944443.

- ^ Jankova-Ajanovska, R; Zimmermann, B; Huber, G; Röck, AW; Bodner, M; Jakovski, Z; Janeska, B; Duma, A; Parson, W (16 June 2016). “Mitochondrial DNA control region analysis of three ethnic groups in the Republic of Macedonia”. Forensic Science International. Genetics. 13: 1–2. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2014.06.013. PMC 4234079. PMID 25051224.

- ^ Peričić, Marijana; Lauc, Lovorka Barać; Klarić, Irena Martinović; Rootsi, Siiri; Janićijević, Branka; Rudan, Igor; Terzić, Rifet; Čolak, Ivanka; Kvesić, Ante; Popović, Dan; Šijački, Ana; Behluli, Ibrahim; Đorđević, Dobrivoje; Efremovska, Ljudmila; Bajec, Đorđe D.; Stefanović, Branislav D.; Villems, Richard; Rudan, Pavao (1 October 2005). “High-Resolution Phylogenetic Analysis of Southeastern Europe Traces Major Episodes of Paternal Gene Flow Among Slavic Populations”. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (10): 1964–1975. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185. PMID 15944443.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Y chromosonal haplogroup distributionanddiversities in seven populations investigated” (PDF). S009.radikal.ru. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Martínez-Cruz, Begoña; Mendizabal, Isabel; Harmant, Christine; de Pablo, Rosario; Ioana, Mihai; Angelicheva, Dora; Kouvatsi, Anastasia; Makukh, Halyna; Netea, Mihai G; Pamjav, Horolma; Zalán, Andrea; Tournev, Ivailo; Marushiakova, Elena; Popov, Vesselin; Bertranpetit, Jaume; Kalaydjieva, Luba; Quintana-Murci, Lluis; Comas, David (June 2016). “Origins, admixture and founder lineages in European Roma”. European Journal of Human Genetics. 24 (6): 937–943. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.201. PMC 4867443. PMID 26374132.

- ^ Regueiro, Maria; Stanojevic, Aleksandar; Chennakrishnaiah, Shilpa; Rivera, Luis; Varljen, Tatjana; Alempijevic, Djordje; Stojkovic, Oliver; Simms, Tanya; Gayden, Tenzin; Herrera, Rene J. (January 2011). “Divergent patrilineal signals in three Roma populations”. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 144 (1): 80–91. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21372. PMID 20878647.

- ^ Bosch, E.; Calafell, F.; Gonzalez-Neira, A.; Flaiz, C.; Mateu, E.; Scheil, H.-G.; Huckenbeck, W.; Efremovska, L.; Mikerezi, I.; Xirotiris, N.; Grasa, C.; Schmidt, H.; Comas, D. (July 2006). “Paternal and maternal lineages in the Balkans show a homogeneous landscape over linguistic barriers, except for the isolated Aromuns”. Annals of Human Genetics. 70 (4): 459–487. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2005.00251.x. PMID 16759179. S2CID 23156886.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Petrejcíková, Eva; Soták, Miroslav; Bernasovská, Jarmila; Bernasovský, Ivan; Sovicová, Adriana; Bôziková, Alexandra; Boronová, Iveta; Gabriková, Dana; Švícková, Petra; Maceková, Sona; Cverhová, Valéria (2010). “The genetic structure of the Slovak population revealed by Y-chromosome polymorphisms”. Anthropological Science. 118 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1537/ase.090203. S2CID 83899895.

- ^ “Croatian national reference Y-STR haplotype database” (PDF). Draganprimorac.com. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ “Y CHROMOSOME SINGLE NUCLEOTIDE POLYMORPHISMS TYPING BY SNaPshot MINISEQUENCING” (PDF). Bjmg.edu.mk. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Peričić, Marijana; Lauc, Lovorka Barać; Klarić, Irena Martinović; Rootsi, Siiri; Janićijević, Branka; Rudan, Igor; Terzić, Rifet; Čolak, Ivanka; Kvesić, Ante; Popović, Dan; Šijački, Ana; Behluli, Ibrahim; Đorđević, Dobrivoje; Efremovska, Ljudmila; Bajec, Đorđe D.; Stefanović, Branislav D.; Villems, Richard; Rudan, Pavao (1 October 2005). “High-Resolution Phylogenetic Analysis of Southeastern Europe Traces Major Episodes of Paternal Gene Flow Among Slavic Populations”. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (10): 1964–1975. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185. PMID 15944443.

- ^ Karachanak, S; Grugni, V; Fornarino, S; Nesheva, D; Al-Zahery, N; Battaglia, V; Carossa, V; Yordanov, Y; Torroni, A; Galabov, AS; Toncheva, D; Semino, O (2013). “Y-chromosome diversity in modern Bulgarians: new clues about their ancestry”. PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e56779. Bibcode:2013PLoSO…856779K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056779. PMC 3590186. PMID 23483890.

- ^ “Participate to the DNA ancestry project for Germany, Austria and Switzerland”. Eupedia.com. 10 January 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Bánfai, Zsolt; Melegh, Béla I.; Sümegi, Katalin; Hadzsiev, Kinga; Miseta, Attila; Kásler, Miklós; Melegh, Béla (13 June 2019). “Revealing the Genetic Impact of the Ottoman Occupation on Ethnic Groups of East-Central Europe and on the Roma Population of the Area”. Frontiers in Genetics. 10: 558. doi:10.3389/fgene.2019.00558. PMC 6585392. PMID 31263480.

- ^ McDougall, Dan (17 August 2008). “Why do the Italians hate us?”. The Guardian. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Hancock, Ian F; Dowd, Siobhan; Djurić, Rajko (2004). The Roads of the Roma: a PEN anthology of Gypsy Writers. Hatfield, United Kingdom: University of Hertfordshire Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-900458-90-3.

- ^ Taylor, Becky (2014). Another Darkness Another Dawn. London UK: Reaktion Books Ltd. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-78023-257-7.

- ^ “Romas are India’s children: Sushma Swaraj”. India.com. 12 February 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ “Can Romas be part of Indian diaspora?”. khaleejtimes.com. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Cherata, Lucian. “ETIMOLOGIA CUVINTELOR “ȚIGAN” sI “(R)ROM””. Scritube (in Romanian). Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Roma, Sinti, Gypsies, Travellers…The Correct Terminology about Roma”, In Other Words project, Web Observatory & Review for Discrimination alerts & Stereotypes deconstruction, archived from the original on 5 October 2012

- ^ Hancock 2002, p. xix.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hancock 2002, p. xxi.

- ^ OED “Romany” first use 1812 in a slang dictionary; “Rom” and “Roma” as plural, first uses by George Burrow in the Introduction to his The Zincali (1846 edition), also using “Rommany”

- ^ Marushiakova, Elena; Popov, Vesselin (2001), “Historical and ethnographic background; gypsies, Roma, Sinti”, in Guy, Will (ed.), Between Past and Future: The Roma of Central and Eastern Europe [with a Foreword by Dr. Ian Hancock], UK: University of Hertfordshire Press, p. 52

- ^ Klimova-Alexander, Illona (2005), The Romani Voice in World Politics: The United Nations and Non-State Actors, Burlington, VT: Ashgate, p. 13

- ^ Rothéa, Xavier. “Les Roms, une nation sans territoire?”. Theyliewedie.org (in French). Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Garner, Bryan A (2011). Dictionary of Legal Usage. Oxford University Press. pp. 400–. ISBN 978-0-19-538420-8.

- ^ O’Nions, Helen (2007). Minority rights protection in international law: the Roma of Europe. Ashgate. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4094-9092-0.

- ^ Hancock 2002, p. xx.

- ^ “List of ethnic groups”. www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ “Dom: The Gypsy community in Jerusalem”. The Institute for Middle East Understanding. 13 February 2007. Archived from the original on 23 May 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (13 February 2007). “Etymology of Romani”. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ Soulis, G (1961), The Gypsies in the Byzantine Empire and the Balkans in the Late Middle Ages, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Trustees for Harvard University, pp. 15, 141–65

- ^ Jump up to:a b White, Karin (1999). “Metal-workers, agriculturists, acrobats, military-people and fortune-tellers: Roma (Gypsies) in and around the Byzantine empire”. Golden Horn. 7 (2). Archived from the original on 20 March 2001. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ Fraser 1992.

- ^ Hancock, Ian (1995). A Handbook of Vlax Romani. Slavica Publishers. p. 17.

- ^ Pocket guide to English usage. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster. 1998. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-87779-514-8.

- ^ Baskin, [by] H.E. Wedeck with the assistance of Wade (1973). Dictionary of gypsy life and lore. New York: Philosophical Library. ISBN 978-0-8065-2985-1.

- ^ Report in Roma Educational Needs in Ireland (PDF), Pavee point, archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2013

- ^ House of Commons Women & Equalities Committee (5 April 2019). “Tackling inequalities faced by Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities”. UK Parliament. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ “Gypsy”. The Free Dictionary.

- ^ Starr, J (1936), An Eastern Christian Sect: the Athinganoi, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Trustees for Harvard University, pp. 29, 93–106

- ^ Bates, Karina. “A Brief History of the Rom”. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ “Book Reviews” (PDF). Population Studies. 48 (2): 365–72. July 1994. doi:10.1080/0032472031000147856.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bereznay, András (2021). Historical Atlas of the Gypsies: Romani History in Maps. Méry Ratio. p. 18/1. ISBN 978-615-6284-10-5.

- ^ Anfuso, Linda (24 February 1994). “gypsies”. Newsgroup: rec.org.sca. Usenet: PaN9Hc2w165w@tinhat.stonemarche.org. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Keil, Charles; Blau, Dick; Keil, Angeliki; Feld, Steven (9 December 2002). Bright Balkan Morning: Romani Lives and the Power of Music in Greek Macedonia. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-8195-6488-7.

- ^ Dr Ian Law; Dr Sarah Swann (28 January 2013). Ethnicity and Education in England and Europe: Gangstas, Geeks and Gorjas. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4094-9484-3. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Ernst Hĺkon Jahr (1992). Language Contact: Theoretical and Empirical Studies. p. 42. ISBN 978-3-11-012802-4. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Rough Guides. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ (Spiezer Schilling, p. 749)

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kenrick, Donald (5 July 2007). Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanis) (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. pp. xx–xxii. ISBN 978-0-8108-6440-5.

- ^ Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A History. pp. 387–88. ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7.

- ^ Antonio Gómez Alfaro. “The Great “Gypsy” Round-up in Spain” (PDF). p. 4.

- ^ Taylor, Becky (2014). Another Darkness Another Dawn. London UK: Reaktion Books Ltd. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-78023-257-7.

- ^ Hancock 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Radu, Delia (8 July 2009), “‘On the Road’: Centuries of Roma History”, World Service, BBC

- ^ Hancock, Ian. “Romanies and the holocaust: a reevaluation and an overview”. Radoc.net. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ “United States Holocaust Memorial Museum”. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Hancock, Ian (2005). “True Romanies and the Holocaust: A Re-evaluation and an overview”. The Historiography of the Holocaust. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 383–96. ISBN 978-1-4039-9927-6. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ “GENOCIDE OF EUROPEAN ROMA (GYPSIES), 1939–1945”. Holocaust Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Silverman 1995.

- ^ Helsinki Watch 1991.

- ^ Denysenko, Marina (12 March 2007). “Sterilised Roma accuse Czechs”. BBC News.

- ^ Thomas, Jeffrey (16 August 2006). “Coercive Sterilization of Romani Women Examined at Hearing: New report focuses on Czech Republic and Slovakia”. Washington File. Bureau of International Information Programs, U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 13 February 2008.

- ^ Weyrauch, Walter Otto (2001), Gypsy Law: Romani Legal Traditions and Culture, p. 210, ISBN 978-0-520-22186-4, Rom have preserved and modified Indian caste system

- ^ “Romani Customs and Traditions: Death Rituals and Customs”. Patrin Web Journal. Archived from the original on 21 August 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ Knipe, David M. (1991). “The Journey of a Lifebody”. hindugateway.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- ^ Hancock 2001, p. 81.

- ^Saul, Nicholas; Tebbut, Susan (2005). Saul, Nicholas; Tebbutt, Susan (eds.). The Role of the Romanies: Images and Counter-Images of ‘Gypsies’/Romanies in European Cultures. Liverpool University Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 978-0-85323-689-4.

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia (8th ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. 2018 – via Credo Reference.

- ^ G. L. Lewis (1991), “ČINGĀNE”, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 2 (2nd ed.), Brill, pp. 40a–41b, ISBN 978-90-04-07026-4

- ^ “Restless Beings Project: Roma Engage”. Restless Beings. 2008–2012. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ Boretzky, Norbert (1995). Romani in Contact: The History, Structure and Sociology of a Language. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. p. 70.

- ^ “Blessed Ceferino Gimenez Malla 1861–1936”. Visit the Saviour. Voveo. December 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lee, Ronald (2002). “The Romani Goddess Kali Sara”. Romano Kapachi. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ “RADOC”. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Roma”. Countries and their Cultures. Advameg. 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ “Romani, Vlax, Southern in Albania Ethnic People Profile”. Joshua Project. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Marushiakova, Elena; Popov, Veselin (2012). “Roma Muslims in the Balkans”. Education of Roma Children in Europe. Council of Europe. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ “Population dupa etnia si religie, pe medii” [Population by ethnicity and religion (on average)] (PDF) (in Romanian). Romanian National Institute of Statistics. 2002. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ “Wiara po romsku”.

- ^ Liégeois, Jean-Pierre (1 January 1994). Roma, Gypsies, Travellers. ISBN 9789287123497.

- ^ Eliopoulos, Nicholas C (2006), Gypsy Council, p. 460, ISBN 978-1-4653-3036-9

- ^ Martinez, Emma (24 February 2011), Flamenco: All You Wanted to Know (Google books), p. 21, ISBN 978-1-60974-470-0

- ^ Hancock 2002, p. 129.

- ^ Cümbüş means fun, Birger Gesthuisen investigates the short history of a 20th-century folk instrument, Rootsworld

- ^ “Meet Your Neighbors” (PDF). opensourcefoundations.org.

- ^ Brogyanyi, Bela; Lipp, Reiner (6 May 1993). Comparative-Historical Linguistics. ISBN 9789027276988.

- ^ Gordon Jr., Raymond G, ed. (2005). “Caló: A language of Spain”. Ethnologue: Languages of the World (15th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL International. ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Matras, Yaron. “Romani Linguistics and Romani Language Projects”. Humanities. The University of Manchester. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Matras, Yaron (October 2005). “The status of Romani in Europe” (PDF). Report Submitted to the Council of Europe’s Language Policy Division: 4. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Achim 2004, p. [page needed].

- ^ Grigore, Delia; Petcuț, Petre; Sandu, Mariana (2005). Istoria și tradițiile minorității rromani (in Romanian). Bucharest: Sigma. p. 36.

- ^ Ștefănescu, Ștefan (1991), Istoria medie a României (in Romanian), vol. I, Bucharest: Editura Universității din București

- ^ “Gypsy/Roma European migrations from 15th century till nowadays”. academia.edu.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Timeline of Romani History”. Patrin Web Journal. Archived from the original on 11 November 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ “Cap. 2: 2.1 Apuntes sobre la situación de la comunidad gitana en la sociedad Española – Anexo III. ‘Gitanos malos, gitanos buenos'” [Chap. 2: 2.1 Notes on the situation of the gypsy community in Spanish society – Affix III. ‘Bad gypsies, good gypsies’]. The Barañí Project – Roma Women (in Spanish). 29 February 2000. Archived from the original on 12 July 2001. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ Taylor, Becky (2014). Another Darkness Another Dawn. London UK: Reaktion Books Ltd. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-78023-257-7.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Samer, Helmut (December 2001). “Maria Theresia and Joseph II: Policies of Assimilation in the Age of Enlightened Absolutism”. Rombase. Karl-Franzens-Universitaet Graz.

- ^ Fraser, Angus (2005). Los gitanos. Ariel. ISBN 978-84-344-6780-4.

- ^ Texto de la pragmática en la Novísima Recopilación. Ley XI, pg. 367 y ss.

- ^ “Gitanos. History and Cultural Relations”. World Culture Encyclopedia. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ Kenrick, Donald. “Roma in Norway”. Patrin Web Journal. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ “The Church of Norway and the Roma of Norway”. World Council of Churches. 3 September 2002.

- ^ Re. Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation (Swiss Banks) Special Master’s Proposals (PDF), 11 September 2000, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2004

- ^ Stone, D, ed. (2004), “Romanies and the Holocaust: A Reevaluation and an Overview”, The Historiography of the Holocaust (article), Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave, archived from the original on 13 November 2013, retrieved 14 February 2009

- ^ “Council of Europe website”. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2009.. European Roma and Travellers Forum (ERTF). 2007. Archived from the original Archived 21 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine on 6 July 2007.

- ^ “Are the Roma primitive or just poor?”. The New York Times (review).

- ^ “Demolita la ‘bidonville’ di Ponte Mammolo” [The ‘slum’ of Mammolo Bridge demolished]. il Giornale (in Italian). IT. 5 December 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Di Caro, Paola (4 November 2007). “Fini: impossibile integrarsi con chi ruba” [Fini: it’s impossible to integrate those who steal]. Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ “European effort spotlights plight of the Roma”. USA Today. 1 February 2005. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ “Europe must break cycle of discrimination facing Roma” (Press release). Amnesty International. 7 April 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ “Europe Roma”. Amnesty International. February 2002. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ Colin Woodard (13 February 2008). “Hungary’s anti-Roma militia grows”. Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ “Roma”. SI: Human Rights Press Point. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ Polansky, Paul (June 2005). “Results of an Enquiry into the Situation of Roma und Ashkali in Kosovo (Dec.2004 to May 2005) – Roma and Ashkali in Kosovo: Persecuted, driven out, poisoned”. GFBV. Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ “National Roma Integration Strategies: a first step in the implementation of the EU Framework” (PDF). European Commission. 21 May 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ Alexander, Harriet (17 February 2014). “Roma on the rubbish dump”. CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ Relief, UN (2010). “Roma in Serbia (excluding Kosovo) on 1 January 2009” (PDF). UN Relief. 8 (1).

- ^ Ringold, Dena; Orenstein, Mitchell Alexander; Wilkens, Erika (2005). Roma in an Expanding Europe – Breaking the Poverty Cycle. World Bank. ISBN 0-8213-5457-4.

- ^ Cahn, Claude (1 January 2007). “Birth of a Nation: Kosovo and the Persecution of Pariah Minorities”. German Law Journal. 8 (1): 81–94. doi:10.1017/S2071832200005423. S2CID 141025735.

- ^ Denysenko, Marina (12 March 2007). “Sterilised Roma accuse Czechs”. BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Bricker, Mindy Kay (12 June 2006). “For Gypsies, Eugenics is a Modern Problem / Czech Practice Dates to Soviet Era”. Newsdesk.

- ^ “Final Statement of the Public Defender of Rights in the Matter of Sterilisations Performed in Contravention of the Law and Proposed Remedial Measures”. The Office of The Public Defender of Rights, Czech Republic. 23 December 2005. Archived from the original on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ Hooper, John (2 November 2007). “Italian woman’s murder prompts expulsion threat to Romanians”. The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ de Zulueta, Tana (30 March 2009). “Italy’s new ghetto?”. The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Kooijman, Hellen (6 April 2012). “Bleak horizon”. EU: Presseurop. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ “The gypsy in my soul: Sinti and Roma in the Netherlands”. Radio Netherlands Archives. 19 September 1999.

- ^ “Negative opinions about Roma, Muslims in several European nations“. Pew Research Center. 11 July 2016.

- ^ “European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism — 6. Minority groups”. Pew Research Center. 14 October 2019.

- ^ “Sondaj IRES: 7 din 10 români nu au încredere în romi”. Radio Free Europe Romania (in Romanian). 8 February 2020.

- ^ “We need to talk about the rising wave of anti-Roma attacks in Europe”. The Independent. 28 July 2019.

- ^ “Unemployment keeps Kosovo’s Roma on the margins”. Deutsche Welle. 17 February 2018.

- ^ “To Europe’s shame, Roma remain stigmatised outsiders – even when they live in mansions”. The Conversation. 25 April 2019.

- ^ “Discrimination against Roma remains widespread in Slovakia says Amnesty International report”. The Slovak Spectator. 22 February 2018.

- ^ “Anti-Roma protests take place in Bulgarian city of Gabrovo”. The Associated Press. 12 April 2019.

- ^ “‘Everybody hates us’: on Sofia’s streets, Roma face racism every day”. The Guardian. 20 October 2019.

- ^ “Roma ghettos in the heart of the EU”. El País. 6 September 2019.

- ^ “Zpráva o stavu romské menšiny: V Česku bylo loni podle odhadů 830 ghett se 127 tisíci obyvateli”. iROZHLAS (in Czech). Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ “Deadly Attack Escalates Violent Trend Against Ukrainian Roma”. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 25 June 2018.

- ^ “Attacked and abandoned: Ukraine’s forgotten Roma”. Al-Jazeera. 23 November 2018.

- ^ “‘Meet us before you reject us’: Ukraine’s Roma refugees face closed doors in Poland”. The Guardian. 10 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ “Roma refugees from Ukraine face Czech xenophobia”. EU Observer. 17 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ “Undocumented Roma Refugees Facing Discrimination As They Flee Ukraine”. Vice. 23 March 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ “Roma people: 10 ways Europe’s biggest minority faces discrimination”. Reuters. 8 April 2019.

- ^ “France sends Roma Gypsies back to Romania”. BBC News. 20 August 2010. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ “Troops patrol French village of Saint-Aignan after riot”. BBC. 10 July 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ “Q&A: France Roma expulsions”. BBC. 15 September 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ “France Begins Controversial Roma Deportations”. Der Spiegel. 19 August 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ “EU may take legal action against France over Roma”. BBC News. 14 September 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ “The Gypsy Lore Society” (Journal).

- ^ Jacquot, Dominique (2006). Le musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg — Cinq siècles de peinture. Strasbourg: Éditions des Musées de Strasbourg. p. 76. ISBN 978-2-901833-78-9.