Indian Roots Of The Iran’s Supreme Leader Revisited Here

By WFY Bureau Desk

From Kintoor to Khomeyn: Tracing Iran’s Revolutionary Roots Back to India

In the vibrant heartland of Uttar Pradesh, nestled amidst the undisturbed plains of Barabanki district, lies a quiet village named Kintoor, a name that would seem unfamiliar to most Indians and irrelevant to modern geopolitics. Yet, this modest settlement, historically a bastion of Shia Islamic scholarship, has become the unlikely talking point in digital circles and diaspora discourse due to a startling connection: the ancestral link between this Indian village and the founding architect of Iran’s Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

This is not a claim fuelled by casual folklore. It is a narrative grounded in oral histories, cultural memory, and compelling genealogical evidence, pointing towards a time when South Asia and West Asia shared far deeper bonds than the borders of today’s politics reveal. In light of present-day tensions between Iran, Israel, and global powers, this forgotten story re-emerges, asking us to consider the remarkable entanglement of migration, memory, and revolution.

Kintoor: A Forgotten Centre of Shia Legacy

Kintoor village, located approximately 70 kilometres from Lucknow and perched along the Ghaghara river, once stood as a centre of theological learning during the Oudh era. It was home to numerous Shia families who migrated to India from Nishapur, Iran, between the 17th and 18th centuries — part of the broader Persian influence during the Mughal and post-Mughal period. These families, identified as Musavi Sayyids, claimed lineage from the Prophet Muhammad through the seventh Shia Imam, Musa al-Kazim.

During this era, Awadh (modern-day Lucknow and surroundings) had become a major cultural and religious hub, especially for Persian-speaking Shias. Kintoor’s intellectual and religious contributions were significant in the development of Indo-Persian traditions, jurisprudence, and literature. In its heyday, the village reportedly had dozens of madrasas, libraries, and clerics who contributed to the larger Shia discourse in the Indian subcontinent.

Today, only five Shia families remain in the village, a telling sign of the erosion of its former identity. However, their memory, rooted in generations of familial knowledge, still honours the migration story of one of their most distinguished sons: Sayyid Ahmad Musavi Hindi.

The Journey of Sayyid Ahmad Musavi Hindi

According to local residents and corroborated by historical accounts, Sayyid Ahmad Musavi was born in Kintoor around 1790. Belonging to a scholarly family of Twelver Shias, he reportedly left India around 1830, during the colonial reordering of Indian society under British rule, to undertake a religious pilgrimage to Najaf in Iraq. The decision to leave was not solely spiritual; many clerics and scholars of the time sought to escape the oppressive control of colonial administrators, who were increasingly regulating religious institutions.

From Najaf, Ahmad Musavi found his way to Khomeyn, a quiet town in the Markazi province of Iran. It was here that he settled permanently by 1834, married into a local Iranian family, and laid the foundations for a future Iranian lineage. His descendants eventually included Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini, born in 1902.

Ahmad’s identity was proudly transregional. Despite leaving India, he retained “Hindi” as a suffix to his name, Sayyid Ahmad Musavi Hindi, which also found its way into his poetic contributions. The suffix symbolised a deep cultural fondness for India and helped preserve his South Asian roots, even after naturalising into Iranian society. His house and landholdings in Khomeyn, acquired through the help of a local benefactor named Yusuf Kamarchi, would later become central in the early life of Ayatollah Khomeini.

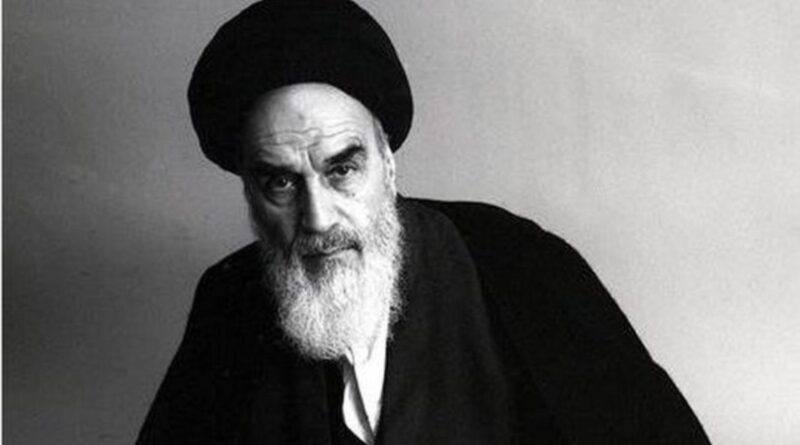

Ruhollah Khomeini: From Cleric to Revolutionary Leader

Ruhollah Khomeini, born two generations later, became one of the most prominent figures in modern Middle Eastern history. The death of his father, Mostafa Musavi, in 1903 left him to be raised by his mother and older brother. From a young age, he was immersed in religious education. He would go on to become a formidable cleric, philosopher, and political activist.

The Pahlavi monarchy in Iran, under Reza Shah and later his son Mohammad Reza Shah, pursued Westernisation and secularism, marginalising clerics from political life. Khomeini emerged as one of the harshest critics of these policies. His criticism of the Shah’s ‘White Revolution’ and alignment with the West led to his exile in 1964.

Khomeini spent years in Turkey, Iraq, and eventually France, where he developed his political ideology blending Islamic governance with anti-imperialist thought. In 1979, his leadership catalysed the Islamic Revolution in Iran, overthrowing the Pahlavi dynasty and establishing a theocratic republic. He became Iran’s first Supreme Leader, a role that continues to define the country’s political architecture to this day.

Oral Histories and the Living Memory of Kintoor

Back in Kintoor, residents like Dr Rehan Kazmi and Syed Nihal Kazmi believe themselves to be distant relatives of Sayyid Ahmad Musavi. Their family, the Kazmis, claim kinship through Ahmad’s cousin, Mufti Mohammad Quli Musavi. While there is no surviving documentation or state record affirming this lineage officially, oral testimony, passed down over two centuries, persists with striking consistency.

The Kazmi household is locally known as “Sayyid Wada,” said to be linked to the original home of Ahmad Musavi. A portrait of Ayatollah Khomeini still adorns the drawing room wall in one of the houses, a silent reminder of the village’s curious brush with global history.

Despite the scepticism from historians over the lack of archival proof, the story continues to live on in the hearts and memories of the villagers, perhaps embodying the broader Indian tradition of preserving legacy through narrative rather than documentation.

Bridging Continents: From Nishapur to Kintoor and Back

It is essential to recognise the broader arc of history here. The Musavi Sayyids originally hailed from Nishapur, Iran, a once-flourishing centre of Islamic learning. As early as the 1700s, they had migrated to India, finding opportunity and patronage under the Nawabs of Awadh. That a descendant of this very family, generations later, would return to Iran and redefine the trajectory of the Islamic world, forms a full circle, a remarkable story of diasporic return.

In today’s geopolitics, Iran’s actions under Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei are often viewed through the lens of resistance against Western powers, particularly the US and Israel. But beneath the militaristic narratives, there lies a lesser-known cultural and emotional truth: a revolutionary ideology that might have partially taken root in the ghats of Barabanki.

Kintoor’s Legacy in the Broader Context

Kintoor’s influence didn’t end with Khomeini’s lineage. The village also produced Justice Syed Karamat Husain, a progressive jurist in colonial India who championed women’s education. He founded the Karamat Husain Muslim Girls’ PG College in Lucknow — an institution that continues to serve the region. Such examples highlight the deep intellectual currents that once ran through the village, long before its present obscurity.

Today, as the Iran-Israel conflict unfolds and Ayatollah Khamenei, Iran’s second Supreme Leader, takes global centre stage, stories like Kintoor’s remind us of the shared pasts that unite nations divided by politics. While Khamenei and Khomeini are not blood relatives, their roles in Iranian history share ideological roots, and in Khomeini’s case, possibly ancestral roots, tied to India.

A Village Remembered, A Legacy Reclaimed

In a world often driven by data, news cycles, and rapidly shifting narratives, the story of Kintoor offers a pause, an invitation to reflect on identity, legacy, and the migration of both people and ideas. The modern Iranian state, for all its complexities, may unknowingly carry a piece of Barabanki in its bloodline.

Though there is yet no scholarly consensus or archaeological confirmation about the exact residence or possessions of Sayyid Ahmad Musavi in Kintoor, the villagers’ passionate belief in their connection to the architect of the Iranian Revolution speaks volumes about cultural continuity. For now, the tale lives on, not in museum archives, but in courtyards, memory, and reverence.

Disclaimer: This article has been prepared by the WFY Bureau Academic Desk for educational and informational purposes. While every effort has been made to present factual, accurate, and balanced content, the article draws from oral traditions, community histories, and secondary references. No direct quotes or unauthorised third-party statements have been included. This article is not intended to support any political or ideological standpoint, nor does it claim legal or genealogical authority. Readers are advised to approach this content as an exploration of socio-cultural intersections between India and Iran.