Marriages and Cohabitation: The World of Ancient India Revisited

Exploring the intriguing dynamics of marriage and live-in relationships in ancient India reveals a fascinating tapestry of cultural practices and societal norms. This journey into the past uncovers how these unions were not only a reflection of personal choices but also deeply intertwined with the social fabric of the time. From arranged marriages to cohabitation, the historical context provides a rich backdrop for understanding the evolution of relationships in this ancient civilisation.

Live-in relationships are capturing attention as Uttarakhand unveils its proposed laws aimed at the registration of live-in couples. This piece refrains from assessing the merits or drawbacks of these laws. In this exploration, I examine the insights our literary texts provide regarding the treatment of various unions within ancient Indian society.

In the ancient Sanskrit epic Mahabharata, a compelling dialogue unfolds as Pandu shares with Kunti a striking revelation about the past. He reflects on a time not so long ago, when women roamed freely, unbound by the confines of their homes. These women pursued their own desires and aspirations, living independently without the need for a husband or the support of relatives. During that time, open marriages were considered the standard practice. This tradition enjoyed social approval, allowing married women to engage with partners beyond their husbands without facing negative judgement (Adi Parva, chapter 122).

It was expected that husbands would maintain a composed demeanour, free from any signs of jealousy, even in such situations. It was not uncommon for wives to embark on brief escapades with other partners, yet more often than not, they would return home. The narrative took a turn, as recounted by Pandu, with the emergence of a boy named Shvetaketu. Disturbed by the sight of his mother departing with an unfamiliar man, the boy voiced his concerns to his father. In response, his father reassured him, clarifying that such behaviour was simply part of their cultural norms.

Shvetaketu, unyielding in his convictions, embarked on a quest for social reform as he matured. His vision, however, leaned toward an imbalance, advocating for married women to adhere to monogamy while placing no such constraints on their male counterparts. Pandu elaborates that during their era, it was quite common for marriages to embrace openness in specific regions, such as Uttar Kuru. Some scholars, including Harvard professor Michael Witzel, intriguingly associate Uttar Kuru with the contemporary region of Uttarakhand. Whether open marriages have been the standard practice in various geographical regions remains a topic of debate. An exploration of the Ramayana, for instance, reveals that Ayodhya approached marriages with distinctly traditional values.

Open marriages were prevalent enough to warrant specific provisions for children who could potentially be born from an extramarital affair. Initially, the mother faced the crucial task of determining the identity of the child’s father—was it her husband, or perhaps another partner? In this scenario, the purported father would take on the crucial role of nurturing and raising the child. In a captivating turn of events, Tara, the wife of Brihaspati, the revered guru of the devas, was drawn to Chandra and embarked on a temporary journey of companionship with him. Upon her return, she discovered she was pregnant. Upon identifying Chandra as the father of her child, the responsibility of raising it fell upon him. Conversely, should the mother assert that the child belonged to her husband, he would be obligated to assume responsibility for the child. The Mahabharata, specifically in the Adi Parva, chapter 5, unfolds a captivating tale featuring Bhrigu, one of the most revered sages, alongside his wife, Puloma. Puloma, one of the wives of Bhrigu, made her way back home after a romantic escapade with a former lover, a man to whom she had been engaged prior to her marriage with Bhrigu. In a remarkable turn of events, Bhrigu embraced his role as the carer for the child, stepping into the shoes of a devoted biological father.

The Mahabharata showcases a fascinating array of marriages, each with its own unique story and significance. In a fascinating exploration of unconventional unions, some marriages were established under specific agreements, where one partner relinquished any claims to future offspring. In the tale of Arjuna and Chitrangada, the enchanting princess of Manipur, we find a captivating narrative of love and destiny. In a tale woven with the threads of love and tradition, Arjuna sought the blessing of Chitrangada’s father, the king of Manipur, to unite in marriage. However, the king’s approval came with a significant stipulation: Arjuna would have to relinquish any claims to the rights of their future children. This intriguing condition adds a layer of complexity to their romantic narrative, as detailed in the Adi Parva, chapter 217. As a consequence, their son Babhruvahana ascended to the role of crown prince in his mother’s kingdom of Manipur, exempt from the call to arms in the epic Kurukshetra war. In a striking juxtaposition, the Pandavas summoned all their other sons to join the battle, even those born from brief unions with their mothers.

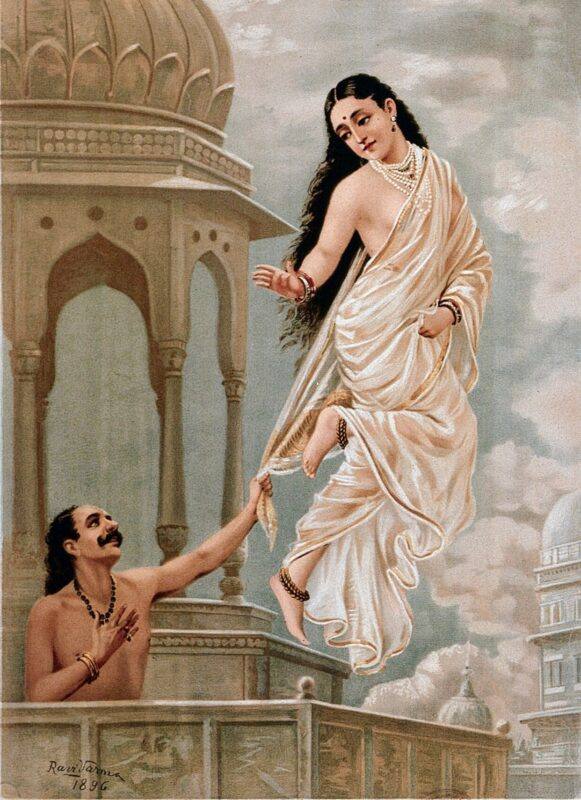

A captivating painting by Raja Ravi Varma featuring the iconic figures of Arjun and Subadhra. In the realm of ancient unions, certain types of gandharva relationships emerged quietly, shrouded in secrecy. However, as noted by Manu in the Manusmriti, there existed alternative forms where the woman took the initiative, often seeking to elope with her chosen partner. This bold move was typically driven by the looming pressure from her family to enter into a marriage with someone else. Within the pages of the Mahabharata, one can discover numerous instances that stand out remarkably. Among the notable events in this epic narrative is the union of Arjuna and Subhadra, who famously eloped from Dwaraka. This daring act was fuelled by the fact that Subhadra’s brother, Balaram, had intentions for her to wed Duryodhan.

One compelling narrative that illustrates a mother’s relinquishment of rights to her future children is found in the tale of Madhavi, as detailed in Udyog Parva, chapters 114-117. In a tale steeped in ancient tradition, the story unfolds around Madhavi, a princess of the impoverished Chandravanshi dynasty. With a heart full of compassion, she aids a determined student named Galav in his quest to gather eight hundred white horses adorned with striking black ears. This remarkable endeavour serves as guru dakshina for his esteemed teacher, Vishwamitra, highlighting the intertwining of duty, sacrifice, and the pursuit of knowledge. Throughout her journey, she engages in a series of temporary unions with three kings, each one a unique chapter in her story. The terms of the contract remained consistent with each iteration. Madhavi remained by the king’s side, her presence unwavering as she awaited the arrival of a son. In a surprising turn of events, she chose to leave without asserting any rights over the child. In a fascinating tradition, the king would present a bride price of two hundred exquisite white horses adorned with striking black ears as a symbol of his commitment to this unique form of marriage. In a poignant conclusion to the narrative, Madhavi’s sons—each having blossomed into remarkably virtuous individuals—united as adults in a heartfelt quest to locate their mother. She was found, and in that moment, she was treated with the utmost honour and love.

The Mahabharata presents a fascinating exploration of polyandry, an intriguing and less common form of marriage that captures the complexities of relationships in ancient narratives. Undoubtedly, the most renowned union among the central figures is that of the Pandavas and Draupadi, characterised by its polyandrous nature. Furthermore, during a conversation with Draupadi’s family in Adi Parva, chapter 168, Yudhishthir highlights instances of polyandry from even earlier periods. He references the notable marriage of Jatila, hailing from the esteemed Gotama lineage of sages, who was wed to seven brothers, among other significant examples.

Historical writings delve into the complexities surrounding divorce. Among the notable works is one authored by Chanakya, often referred to as Kautilya, who served as the esteemed mentor to Emperor Chandragupta Maurya. The Arthashastra, a renowned manual on political science and law, was penned by him. In the pages of the Arthashastra, specifically in Book 3, chapter 3, the concept of divorce is explored through the lens of mutual enmity. It articulates that when both spouses experience a sense of paraspara dveshat-moksha, or a desire for liberation from their shared animosity, divorce becomes a permissible option. The stance taken was notably more traditional when it came to matters of unilateral separation or remarriage. Traditionally, unilateral divorce was not permitted for either gender. Nevertheless, it asserted that women had the right to leave their husbands under certain circumstances. These included instances where the husbands displayed poor character, were absent for extended periods without explanation, or experienced a loss of virility, among various other justifications. In a fascinating exploration of marital customs, it is noted that men had the opportunity to remarry under specific circumstances. If their wives were childless, they could indeed seek new partnerships, albeit after a considerable waiting period. This intriguing practice highlights the complexities of relationships and societal expectations in historical contexts. In the event of remarriage prior to a 12-year period, individuals were required to provide financial compensation to their former spouses, in addition to facing a state-imposed fine, as outlined in Book 3, chapter 2. In certain circumstances, women had the opportunity to remarry, particularly if their husbands had been absent for an extended period—specifically, around ten months without any communication. This provision also extended to widows, allowing them the chance to find companionship once more (Book 3, chapters 2 to 4). Interestingly, the Rig Veda touches upon the topic of widow remarriage in its renowned “burial hymn” (RV 10.18).

The Kamasutra, an ancient text, delves into the topic of widow remarriage with notable depth in Book 4, chapter 2. The author expresses a progressive view, asserting that a widow should have the freedom to choose her partner based on her preferences and what she believes will be a suitable match.

Despite the significant focus on marriage found in our ancient texts, it was not deemed essential to enter into matrimony. Indeed, numerous women—and men—garnered immense respect, even without ever entering into marriage. In Harita’s Dharmasutra, the text reveals that women are categorised as either sadya vadhus or brahmavadinis. In a fascinating contrast, the first category embraced the traditional householder lifestyle, while the brahmavadinis embarked on intellectual journeys as scholars, often choosing not to marry, though exceptions did exist. In the ancient text of the Grihya-sutra by Ashwalayana, a fascinating tradition unfolds. It presents a curated list of esteemed teachers whose blessings are essential before embarking on the journey of self-study. This practice highlights the deep respect for knowledge and the revered figures who guide seekers on their intellectual paths. The list featured a number of remarkable female educators, among them Gargi, Sulabha, and Vadava Pratitheyi. Gargi, a prominent figure in the Upanishads, and Sulabha, noted in the Mahabharata, are both recognised for their single status. In a fascinating turn of events, Lilavati, the daughter of the renowned mathematician Bhaskara II, chose to remain single, utilising her exceptional mathematical skills to forge her own path and support herself. Historical writings reveal intriguing accounts of single fathers from ancient times. Among the most renowned figures in ancient literature stands Ved Vyas, celebrated as the author of the epic Mahabharata. Numerous Puranas narrate the remarkable story of Ved Vyas, who single-handedly raised his son Suka, choosing the path of solitude over marriage. Drona, hailing from the esteemed Bharadwaj clan, had a father who remained unmarried.

A stunning chromolithograph by the renowned artist Raja Ravi Varma captures the enchanting tale of Pururavas and Urvashi, showcasing the intricate details and vibrant colours that bring this mythological narrative to life. This artwork, available on Wikimedia Commons, exemplifies Varma’s mastery in blending traditional themes with a modern artistic approach.

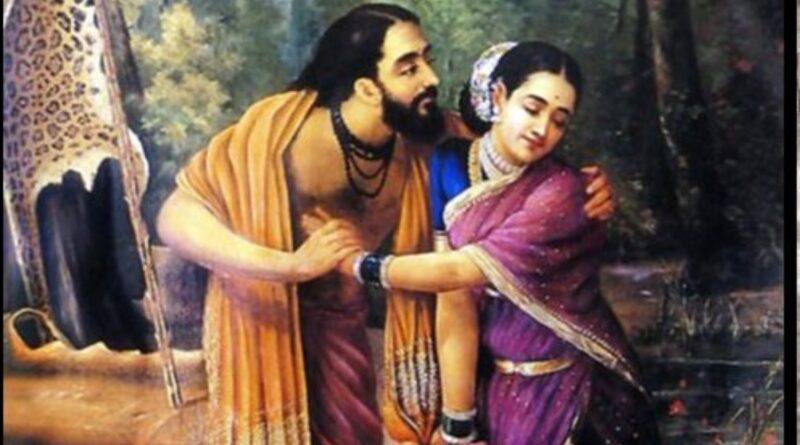

The time has arrived to explore the fascinating concept of gandharva vivaha. Among the pages of ancient law texts, including various Dharmasutras and Grihyasutras, one can find references to this as one of the eight widely recognised forms of marriage. In contrast to various forms of marriage that often involve elaborate rituals or ceremonies, the Gandharva union stands out for its simplicity. This unique union requires no ceremonies, witnesses, or even parental consent, highlighting a more personal and direct approach to commitment. The union was formed purely on the foundation of shared emotions.

In the Dharmasutra, Baudhayana delves into the various forms of marriage, highlighting the gandharva marriage in Book 1, chapter 11.20.16. He notes, “gandharvamapyeke prashansanti sarvesham snehanugatvat,” which translates to the idea that this form of marriage is esteemed by all due to its foundation in mutual affection. Similarly, Vatsyayana, in the Kamasutra, extols the virtues of gandharva marriages, asserting that their roots in prior love enhance the likelihood of happiness. Sanskrit literature brims with captivating tales of unions that intertwine romance with an intriguing blend of uncertainty and danger. In the renowned play Abhigyana Shakuntalam by Kalidasa, the character Shakuntala engages in a gandharva union with Dushyanta, showcasing a captivating moment in the narrative. As the story unfolds, Dushyanta finds himself at a crossroads, compelled to depart in haste. Later, when a visibly pregnant Shakuntala seeks him out, the unexpected occurs: he publicly disavows any knowledge of her. Gandharva unions take centre stage in the Brihatkatha, an expansive anthology of narratives woven within narratives. They also make notable appearances in the works of the playwright Bhasa, particularly in the play Avimaraka, as well as in Dandin’s celebrated novel, Dashakumaracarita, which chronicles the adventures of ten young men. In many of these narratives, a captivating union unfolds between a princess and her chosen partner, a figure of lesser status whom her family would have disapproved of. This enchanting tale explores the complexities of love that transcends societal boundaries. In a discreet arrangement, she concealed him within her lavish apartments, all while her attendants were fully aware and supportive of the secretive endeavour. Challenges arise when the girl’s parents unexpectedly discover the truth. Their acceptance of the marriage would likely be hesitant. In certain tales, such as that of Avimaraka, the search for a suitable partner often led to unexpected choices, like a shepherd who captured the heart of a princess. In these narratives, conflicts often reached a satisfying conclusion, typically through the male partner’s actions that demonstrated his value in the eyes of the woman’s family. One fascinating example of this phenomenon can be found in the life of Bilhana, a poet from Kashmir who flourished in the eleventh century. In a tale woven with romance and intrigue, Bilhana, the esteemed court poet, found himself entwined in a clandestine affair with the king’s daughter, culminating in a sacred gandharva union. In a dramatic turn of events, the king found himself consumed by rage over the clandestine affair, contemplating the harshest of punishments for Bilhana. In a captivating turn of events, Bilhana crafted and performed an exquisite collection of verses known as the Caurapancasika (Fifty Verses of a Love Thief), celebrating his enchanting romance with the princess. Moved by the exquisite quality of the poetry, the king extended his forgiveness and formally united him in marriage with the princess.

Initially, these forms of Gandharva unions were shrouded in secrecy. However, Manu’s writings in the Manusmriti reveal another scenario where a woman would take the initiative to elope with a man, often driven by the pressure from her family to marry someone else. Within the pages of the Mahabharata, one can find numerous instances that exemplify its rich narrative tapestry. Among the notable tales of love and elopement, the union of Krishna and Rukmini stands out. In a bold move, Rukmini reaches out to Krishna, seeking his help to escape the pressures of her family, who are intent on marrying her off to Shishupal. Similarly, the romance between Arjuna and Subhadra captures the imagination, as the couple flees from Dwaraka, defying the wishes of Subhadra’s brother Balaram, who favours a match with Duryodhan. One of the most renowned historical unions is that of King Prithviraj Chauhan and the enchanting princess Samyukta. In a strategic move, Prithviraj found himself intentionally left out of Samyukta’s swayamvar, effectively removing any possibility for her to choose him as her husband. Yet, he remained concealed, and together they made their daring escape.

It is fascinating to note that all the lawgivers, the architects of the Dharmasutras, acknowledged the existence of gandharva unions, even when they occurred without the approval of parents. In a surprising twist, even Manu, often viewed as the epitome of ultra-conservatism, acknowledged in the Manusmriti (9.90-91) that when girls reach a certain age, they possess the right to select their own husbands. Remarkably, he stated that neither the girls nor the husbands they choose would bear any blame for this decision. The Rigvedic hymns reveal intriguing insights into the romantic dynamics of Vedic society, highlighting the existence of relationships between unmarried girls and young men.

Discussions surrounding divorce can be traced back to ancient texts. Among the notable works is one authored by Chanakya, who is also recognised as Kautilya, serving as the esteemed mentor to Emperor Chandragupta Maurya. The Arthashastra, a renowned manual on political science and law, was penned by him. According to the Arthashastra, specifically in Book 3, chapter 3, divorce is permissible when both partners experience a shared sense of animosity, referred to as paraspara dveshat-moksha, which translates to a desire for liberation from mutual hostility.

In the timeless pages of the Kamasutra, Vatsyayana devotes an entire book—Book 3—to offering guidance to those seeking the path of love marriage, addressing both men and women with insightful counsel. He provides guidance on how to secure parental approval after pursuing Gandharva unions. The couple is encouraged to gather kusha grass, ignite a fire, and circle around it in a meaningful ritual. In a fascinating exploration of marital traditions, it is revealed that even in the absence of a priest or human witnesses, a union can still hold significant validity. This unique scenario suggests that the couple’s parents would find it challenging to dispute the legitimacy of the marriage, as fire, a sacred element in Hindu customs, serves as the principal witness. This underscores the profound importance of fire in the rituals of Hindu marriages, highlighting its role as a divine observer in the sacred bond between two individuals. In the ongoing discourse, one might consider live-in relationships as akin to gandharva unions. The legislation mandating registration could be seen as a significant move towards formal acknowledgement and legitimacy, much like the essential functions of fire and kusha grass.

In the tapestry of ancient society, the intricate web of unions showcased a remarkable complexity. However, amidst this rich landscape, children occasionally found themselves in precarious situations. In the intriguing world of Gandharva unions, a fascinating dynamic unfolds where fathers, much like Dushyanta, had the power to deny paternity. Numerous tales emerged of children born to apsaras, who were sent on missions to divert sages from their intense penances. When biological fathers turned their backs, these children found themselves at the mercy of compassionate strangers, as even the apsaras were reluctant to take on the role of carers. Abandoned by her biological parents, Shakuntala found solace in the loving embrace of Sage Kanva, who adopted her and provided her with a nurturing home. In some heartbreaking circumstances, children have been born from acts of violence, leaving both parents in a position where they may feel unprepared or unwilling to take on the responsibility of raising them. During that era, societal norms often mandated that the perpetrator of a rape be responsible for raising any children resulting from the assault. However, in reality, this expectation was not consistently upheld. In a troubling narrative, Brihaspati committed an act of violence against a female relative and a child, leading to the birth of Bharadwaj. Brihaspati ultimately declined to assume responsibility for the child. Both the rape victim and her husband declined. In a heartwarming turn of events, the baby’s maternal grandparents took on the responsibility of raising him. He blossomed into a renowned sage.

Throughout history, ancient lawgivers displayed a remarkable awareness of societal challenges, as evidenced by the explicit recognition of two distinct forms of marriage rooted in force or fraud within numerous legal texts. In the realm of ancient traditions, there existed rakshasa marriages, characterised by the abduction of a woman, alongside pishacha unions, where intoxicants or drugs were employed by the man, echoing the troubling dynamics of date rape in contemporary society. While the authors of the Dharmasutras did not endorse these practices, their acknowledgement of them as forms of marriage served a significant purpose. It aimed to offer legal protection to children born from such unions, legitimising their status and enhancing the rights of abducted women, ensuring they were afforded certain protections and entitlements. It is clear that the system had its flaws, with certain loopholes remaining evident. In a noteworthy development, certain aspects of the proposed live-in laws today aim to safeguard the rights of women and children. In a notable development, when live-in couples choose to register their relationship, any children they welcome into the world are deemed legitimate. This legal recognition also empowers the woman to seek maintenance from her male partner, ensuring her rights are upheld in this modern family dynamic.

It can be argued that society has indeed come full circle. In the annals of history, one can observe a remarkable fluidity within ancient societies, where individuals made a diverse array of choices concerning their personal lives. A remarkable array of marriages and other unions addressed this situation. In a similar vein, the situation presented a myriad of intricate challenges that required the attention of lawmakers and intellectuals alike. A notable example can be found in the Arthashastra, which strives to protect the inheritance rights of children born to a mother who remarries and may have additional offspring in the future. At a certain juncture, society took on a more rigid, conservative, and homogeneous stance regarding these issues. Once more, we find ourselves at a crossroads where individuals embrace a variety of lifestyles and beliefs. It’s no surprise that our legal framework must evolve to address the intricacies that come with such diversity.

This is the right blog for anyone who wants to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I actually would want…HaHa). You definitely put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Great stuff, just great!

Thank you for helping out, fantastic information.