Why Is Onam So Special To The Malayalees World Over?

By Melwyn Williams | September 2025 Edition | Cover Story

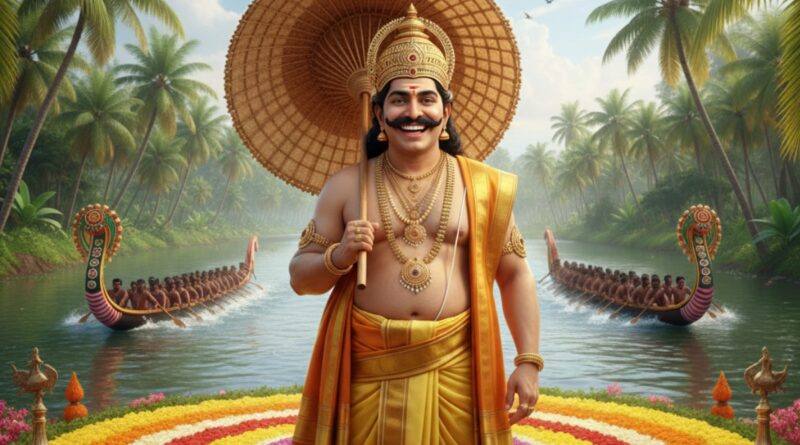

A Festival Larger Than Life

Among the countless festivals of India, few carry the weight of memory, myth, and identity in the way Onam does. To Malayalees across the world, Onam is more than a date in the calendar. It is the echo of a golden age, the joy of harvest, and the reassurance of belonging. Every year, during the Malayalam month of Chingam (August–September), Malayalees welcome their legendary king Mahabali, or Maveli, believed to return from the netherworld to see his people. In their celebration, they make sure he sees no sorrow, only abundance, so that he goes back convinced that Kerala is still as prosperous as during his reign.

This act of joyous pretence is what makes Onam extraordinary. It is not a festival of grief or fear, but one of optimism and harmony. It is celebrated by Hindus, Christians, and Muslims alike in Kerala, and by millions of Malayalees living far away from home. It is both local and global, ancient and modern, deeply religious yet broadly cultural. For Malayalees, Onam is an anchor, the one festival that unites them across caste, creed, geography, and generation.

The Legend of King Mahabali: Ruler Loved Beyond Measure

The story of Mahabali is central to Onam’s magic. Mahabali, grandson of Prahlada, was an Asura king, yet unlike the stereotypical demons of mythology, he ruled with justice, generosity, and humility. Under his reign, Kerala witnessed a golden era where deceit was absent, poverty unknown, and everyone was equal.

But such prosperity stirred envy among the Devas, who sought Lord Vishnu’s help. Vishnu chose to test Mahabali in a unique way. Taking the form of a dwarf Brahmin named Vamana, he appeared before the king during a grand yajna and asked for three paces of land. Against his guru Shukracharya’s warning, Mahabali agreed. Vamana grew into the cosmic form of Trivikrama.

With his first step, he covered the earth. With the second, he spanned the heavens. For the third, Mahabali humbly offered his head.

Vishnu pressed him into the netherworld but, moved by his devotion, granted him the boon of visiting his people once every year. That annual return became the festival of Onam. To this day, Malayalees decorate their homes, wear new clothes, prepare feasts, and design floral carpets so their king will see joy and prosperity all around. They hide their hardships, for they do not want their beloved ruler to be saddened. This exchange of love between ruler and ruled is unlike any other in mythology. It is a reminder of what governance ought to be: just, generous, and bound by affection.

Historical and Cultural Roots of Onam

Beyond mythology, Onam carries a long and layered history. References to harvest festivals resembling Onam are found in Sangam literature as early as the 2nd century CE. In Maduraikkanchi, a Tamil poem from that era, the poet describes decorated streets, bustling markets, joyous dances, and the sharing of food after the paddy harvest. Scholars see this as one of the earliest literary echoes of Onam. Other texts like Perumpanarruppadai also describe seasonal rituals tied to prosperity, suggesting that the celebration of plenty was an integral part of life in southern India even before Kerala took shape as a distinct cultural region.

As centuries passed, Onam became more deeply associated with the land and people of Kerala. Mediaeval temple inscriptions at Trikkakkara and Tiruvalla record celebrations linked to Vamana and Mahabali. Onam was not confined to Kerala alone. Traces of similar celebrations are found in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka, before the Chera dynasty wove it firmly into Kerala’s identity.

Inscriptions from temples such as Trikkakkara near Kochi, Tiruvalla in central Kerala, and Thrissur record donations made specifically during the Onam season. The Trikkakkara Temple, dedicated to Vamana, has over 400 inscriptions dating from the 10th to 13th centuries. These inscriptions not only prove the antiquity of Onam but also reveal how it was tied to temple economies and local governance. Traders, farmers, and artisans all came together during the festival, making it a centre for cultural and commercial exchange.

Onam is deeply agrarian at heart. Chingam follows Karkidakam, a month of scarcity when heavy monsoons make farming difficult. With Chingam comes the first harvest of rice, celebrated as Niraputhari. The saying Onathinu Puthariyunnuka, “let there be new grain for Onam”, underlines its agricultural essence.

The Parasurama legend adds another dimension. According to this myth, Kerala was reclaimed from the sea by Parasurama, the sixth incarnation of Vishnu, who threw his axe into the ocean and commanded the waters to retreat. The fertile land thus created became home to a people who honoured their new beginnings through annual thanksgiving rituals. Many historians suggest that Onam absorbed this thanksgiving element, linking fertility of the land to divine blessing and human effort.

Onam also evolved under dynastic influence. During the reign of the Cheras, the festival gained prominence as a unifying cultural marker. In later centuries, the Travancore kings patronised Onam, using it as a moment to showcase royal generosity. Public feasts, temple fairs, and performances funded by the state became traditions, reinforcing the sense that Onam was not only about myth but also about governance and social order. In 1961, Kerala officially declared Onam the “National Festival of Kerala”, recognising its inclusive and unifying nature.

At its heart, Onam has always been more than a religious observance. It is a cultural statement that blends myth, literature, history, agriculture, and politics into one. This layering explains why Onam is so deeply cherished — it belongs equally to history and imagination, to the soil and to the spirit.

Even today, Onam is Kerala’s economic engine. According to recent figures, retail sales in Kerala during Onam cross ₹15,000 crore annually, with textiles and food industries contributing the bulk. Markets witness record footfall, and even NRIs send remittances to families to celebrate Onam. The festival is thus both spiritual memory and economic lifeline.

A Festival Beyond Caste and Creed

Onam’s uniqueness lies in its inclusivity. Christians and Muslims participate with equal enthusiasm. Churches organise Onam feasts, mosques join community pookkalam competitions, and schools across the state host events that bring all students together.

For Malayalees, Onam is cultural rather than narrowly religious. It embodies the spirit of Mahabali’s reign, where justice and equality prevailed. The folk song Maveli Naadu Vaneedum Kalam recalls a time of perfect harmony, and each Onam celebration is a conscious recreation of that ideal.

This inclusivity also explains why Onam resonates so strongly with the diaspora. In foreign lands where religious festivals are often celebrated within communities, Onam becomes a cultural bridge that Malayalees proudly share with friends of every background.

The Ten Days of Onam: Rituals, Joy, and Symbolism

Onam is not a single day but a ten-day journey, each with its distinct flavour and meaning:

- Atham – Atham marks the beginning. In Thripunithura, near Kochi, the Athachamayam procession still echoes the grandeur of royal times. Once led by the king of Kochi, it now features caparisoned elephants, folk dancers, musicians, floats, and cultural pageants. It is a celebration of inclusivity, where art forms from across Kerala are displayed. In households, the first pookkalam is laid with a simple design of yellow thumba flowers, symbolising purity and humility. Clay figures of Mahabali and Vamana are installed in courtyards.

- Chithira – Chithira focuses on cleaning. Families sweep, scrub, and sometimes repaint their homes. Fresh flowers are added to the pookkalam, which begins to grow in size. In rural Kerala, this day is also when fields are inspected after the monsoons, as farmers prepare for the harvest.

- Chodhi – Chodhi is the day of shopping. Families purchase Onakkodi, the new clothes that every Malayalee wears during Onam. In earlier times, even the poorest families ensured they had at least a simple new garment. Today, the textile industry reports sales exceeding ₹1,000 crore during Onam, with kasavu sarees and mundus dominating purchases.

- Visakam – Visakam is considered highly auspicious. Markets bustle with produce, and pookkalam competitions begin in schools and neighbourhoods. For homemakers, it is the time to start grinding coconut and spices in preparation for the Sadya. For children, it is a day of playful contests in traditional games.

- Anizham – Anizham is dominated by Vallamkali, the snake boat races of central Kerala. The boats, manned by over a hundred oarsmen, cut through rivers in perfect rhythm to the chanting of vanchippattu. The Nehru Trophy Boat Race in Alappuzha and the Aranmula Uthrattadi Boat Race are highlights, drawing thousands of spectators, including international tourists. The races are not merely sport but symbols of teamwork, discipline, and communal harmony.

- Thriketta – Thriketta is the day of family reunions. People travel to their ancestral homes, and gifts are exchanged. In some regions, this day is marked by cultural gatherings where children perform folk songs and dances for elders. Gifts are exchanged.

- Moolam – Moolam brings temples to life with smaller Sadyas and public festivities. Pulikali performers begin painting themselves for the tiger dance, and women rehearse for Thiruvathirakali and Kaikottikali. In villages, swings are hung on trees, and children sing Onappaattukal while swaying in the breeze.

- Pooradam – Pooradam introduces clay figures called Onathappan, representing Mahabali and Vamana. Children mould these idols, decorate them with rice paste, and place them in courtyards. The pookkalam grows in complexity, often with eight concentric layers by this stage.

- Uthradom – Known as the “first Onam” or Onnam Onam. It is believed that Mahabali arrives on this day. Markets swell with crowds, and provisions for the grand feast are stocked. In Thrissur, Onakkazhcha markets see farmers bringing produce as offerings to temples, creating a carnival atmosphere.

- Thiruvonam – Thiruvonam is the climax. Families wake early, bathe, and wear their Onakkodi. Pookkalams are completed in full splendour. Onasadya, the grand vegetarian feast, is prepared and served on banana leaves. In some households, food is first offered to the poor before the family eats, a gesture symbolising Mahabali’s generosity. Gifts are exchanged, elders bless children, and the day concludes with cultural programmes.

Some communities also observe Avittom, the day after Thiruvonam, as the farewell to Mahabali. Clay idols are immersed in water or stored away, and pookkalams are dismantled. It is a symbolic reminder that joy is fleeting, yet will return the following year.

Today, the ten days of Onam have adapted to modern lifestyles. In cities, apartments host communal pookkalam competitions and Sadyas in common halls. Schools dedicate entire weeks to cultural activities, blending traditional games with modern events. IT parks and corporate offices hold Onam celebrations, where employees in kasavu attire share Sadhya and perform dances. This adaptation ensures that Onam continues to thrive, whether in a village courtyard or a glass-and-steel office tower.

Cultural Expressions: The Heartbeat of Onam in Kerala

Onam is experienced not just through legend or ritual but through the vivid cultural fabric it weaves across Kerala. Each town and village brings its own flavour, but several traditions have come to symbolise the festival universally. From Pulikali in Thrissur to elephant processions in temples, Onam turns Kerala into a living stage. Kaikottikali, Thiruvathirakali, Kathakali, Onathallu, and Kummattikali — each adds richness to the festival. Children on swings, decorated elephants, and drums fill the atmosphere.

Onam is not only about legend and ritual but also about the sights, sounds, and flavours that fill Kerala during the season. It is during this time that art, sport, and community expression come together in their most vibrant forms.

Pookkalam: Floral Carpets of Devotion

One of the most recognisable images of Onam is the pookkalam, elaborate floral carpets laid at the entrance of homes. Starting with a small circle of yellow thumba flowers on Atham, the design grows larger and more intricate each day until Thiruvonam. Traditionally, flowers from Kerala’s own fields were used, including the sacred dashapushpam (ten medicinal flowers). Today, however, with urbanisation, households often rely on markets, where the flower trade peaks during Onam. According to market reports, the state consumes over 900 tonnes of flowers during Onam, valued at more than ₹100 crore. Pookkalam competitions are held in schools, colleges, and offices, turning courtyards into canvases of colour and creativity.

Vallamkali: The Snake Boat Race

Perhaps no event embodies the energy of Onam more than Vallamkali, the majestic snake boat races of Kerala’s backwaters. These chundan vallams, sleek and narrow, measure over 100 feet in length and hold up to 150 oarsmen. Rowing in perfect rhythm, guided by the chants of vanchippattu and the beat of drums, the crews cut through the water at breathtaking speed. The Aranmula Uthrattadi race, linked to the Parthasarathy Temple, is considered sacred, while the Nehru Trophy Boat Race at Alappuzha is the most famous, attracting international tourists and media. Vallamkali is more than a sport — it is a symbol of discipline, coordination, and collective spirit, values that mirror Mahabali’s ideal kingdom.

Today, they are symbols of community spirit, teamwork, and sporting glory, attracting thousands of tourists each year.

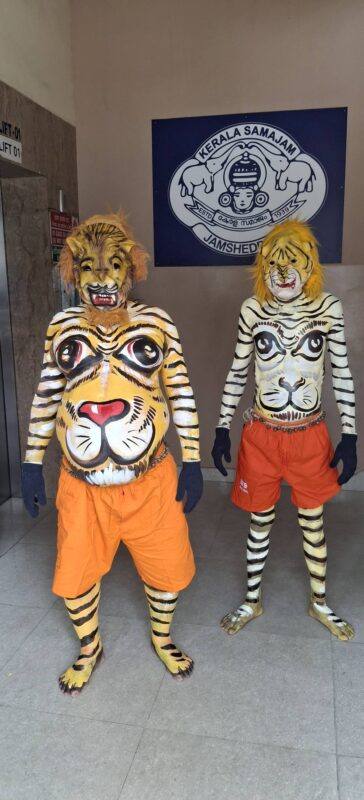

Pulikali: The Dance of the Tigers

In Thrissur, men painted as tigers and hunters prowl the streets in Pulikali, literally “play of the tigers”. Introduced by Maharaja Rama Varma Sakthan Thampuran over 200 years ago, Pulikali reflects both the wildness and humour of Kerala’s cultural imagination. With bodies painted in bright yellow, black, and red, and accompanied by the beats of udukku and thakil, the performers re-enact the eternal dance between hunter and prey. The crowds cheer, laugh, and join in, making Pulikali one of the most democratic folk arts, where no professional training is required, only enthusiasm and stamina. Its popularity has grown so much that it is now featured in tourism campaigns, symbolising Kerala’s festive spirit.

Kaikottikali and Thiruvathirakali

Women’s dances play an equally important role in Onam celebrations. Kaikottikali, the clap dance, features women dressed in kasavu sarees performing in circles, clapping rhythmically to folk songs. Thiruvathirakali, more graceful and slower, is often performed around a lit nilavilakku (traditional lamp). These dances are both artistic expressions and acts of devotion, bringing together women of all ages in communal harmony.

Kathakali and Classical Arts

Onam also brings out Kerala’s classical heritage. Kathakali, the grand dance-drama, is staged in temples and cultural venues. Performances narrate episodes from the Mahabharata and Ramayana, combining elaborate costumes, painted faces, and intricate gestures. Koodiyattam and Chakyar Koothu, ancient Sanskrit theatre forms, also find a stage during Onam festivals. These classical arts remind the audience that Onam is not only about revelry but also about storytelling and cultural continuity.

Onathallu and Martial Traditions

In some parts of Palakkad and Thrissur, Onathallu, a mock fight or martial art performance, is still staged. Men gather in temple courtyards and simulate combat, recalling Kerala’s martial traditions and its historic defence of justice. It is seen as a symbolic act of strength and discipline, qualities admired during Mahabali’s reign.

Elephant Processions and Village Fairs

Elephants adorned with nettipattam (gold-plated forehead ornaments) parade through temple towns, while swings tied to tall trees remind one of Onam’s rustic pleasures. Elephants adorned with gold-plated ornaments, silk umbrellas, and bells form part of temple processions during Onam. They walk majestically through towns while crowds cheer. Village fairs, selling toys, sweets, and household goods, add to the festive atmosphere. For children, swings tied to tall trees, decorated with flowers and leaves, remain one of the simplest yet most cherished joys of Onam. Children singing Onappaattukal while swinging is still a nostalgic sight in many villages.

All these expressions — whether the roar of Pulikali, the grace of Thiruvathirakali, the discipline of Vallamkali, or the fragrance of pookkalams — weave together the sensory richness of Onam. They transform Kerala into a theatre of colour and sound, ensuring that the spirit of Mahabali’s golden reign continues to live not only in stories but also in lived experiences.

Onasadya: The Feast of Abundance

If there is one tradition that epitomises Onam, it is the Onasadya. The grand vegetarian banquet served on banana leaves is a culinary marvel and a cultural declaration.

A Sadhya typically consists of 26 to 64 dishes, though some records mention even larger spreads. The dishes represent the diversity of Kerala cuisine: avial, olan, sambar, erissery, pulissery, pachadi, thoran, and more. Pickles, chips, pappadam, and payasam complete the experience.

Each item has its specific place on the banana leaf, and each is meant to balance flavour — spicy, sweet, tangy, and bitter — in a harmony that reflects life itself. The famous proverb Kaanam Vittum Onam Unnanam, “One must have the Onam feast even if one must sell one’s property,” captures the festival’s cultural emphasis on generosity and sharing.

Economically, the Sadhya is a powerhouse. Restaurants across Kerala serve Sadhya during the season, and prices can range from ₹600 to ₹2,500 per plate depending on the spread. The demand is such that hotels, caterers, and even IT company canteens compete to provide the most authentic experience. Outside Kerala, especially in the Gulf and Western countries, Sadya has become a cultural brand, offered in Indian restaurants to packed houses of Malayalees and curious locals.

Onam in the Malayalee Diaspora

JAMSHEDPUR

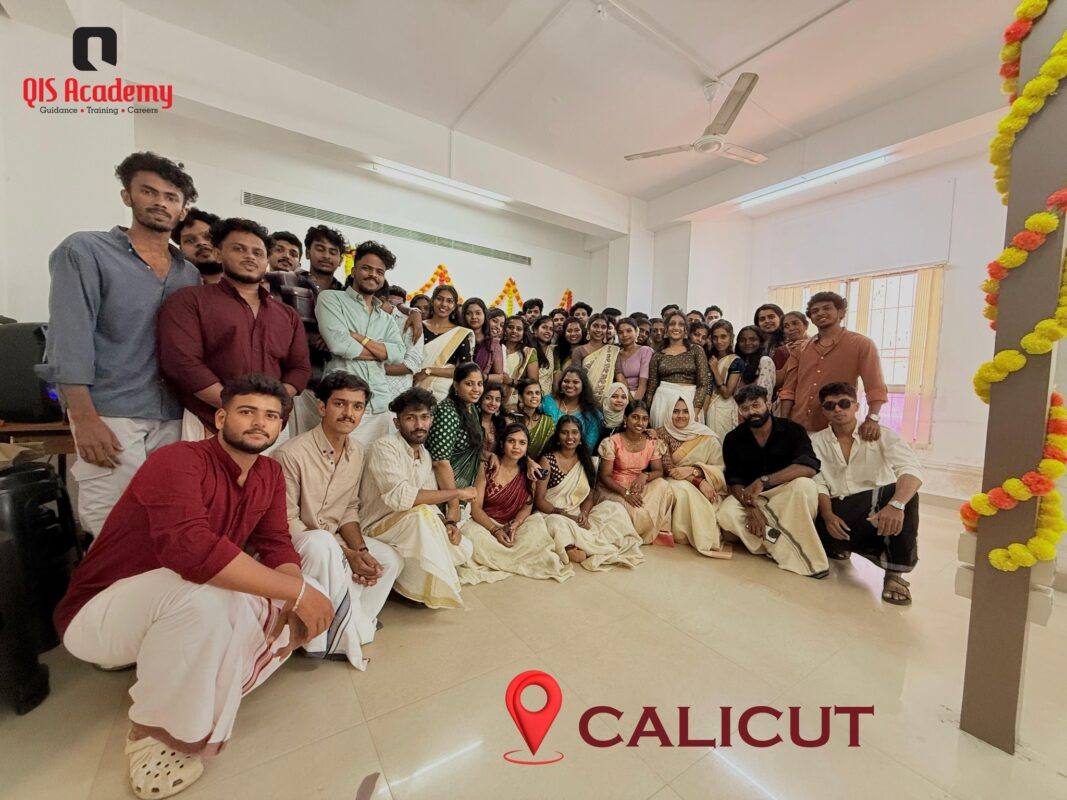

For the Malayalee diaspora, Onam is not merely nostalgia but a bridge to home. With more than 3.5 million Malayalees spread across the globe, the festival has crossed borders and gained a global identity. Whether in the Gulf, Europe, North America, Africa, or Australia, Onam becomes an opportunity not just to gather but to showcase Kerala’s heritage to the wider world.

United Arab Emirates and the Gulf

Bahrain

Muscat

KUWAIT

DUBAI

QATAR

The United Arab Emirates, home to nearly one million Malayalees, witnesses some of the most extravagant Onam celebrations outside India. Stadiums in Dubai and Abu Dhabi are booked for cultural nights where artists fly in from Kerala to perform. Retail chains like Lulu Group import tonnes of vegetables, banana leaves, and even flowers to meet the demand. Lulu alone reports selling more than 350 tonnes of produce during the season. Restaurants serve Sadya buffets for thousands, often selling out weeks in advance.

For labour camps, community organisations sponsor free Onam feasts, ensuring that even those far from home feel included. In Qatar, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, similar celebrations are organised, reflecting how the Gulf has become an extension of Kerala’s cultural geography.

United Kingdom

SUSSEX

COLCHESTER, ESSEX

In the United Kingdom, Onam has taken on innovative forms. The Kerala Cultural Forum and Malayalee associations organise boat races using dragon boats on reservoirs, such as the famous event at Rugby’s Draycote Water, which drew over 5,000 people in 2022. Pookkalams are created with roses, lilies, and other British flowers, giving the tradition a unique adaptation. Community centres in London, Birmingham, and Manchester host Thiruvathirakali, Kathakali, and music shows.

British politicians are often invited as guests of honour, highlighting Onam’s role as a cultural ambassador.

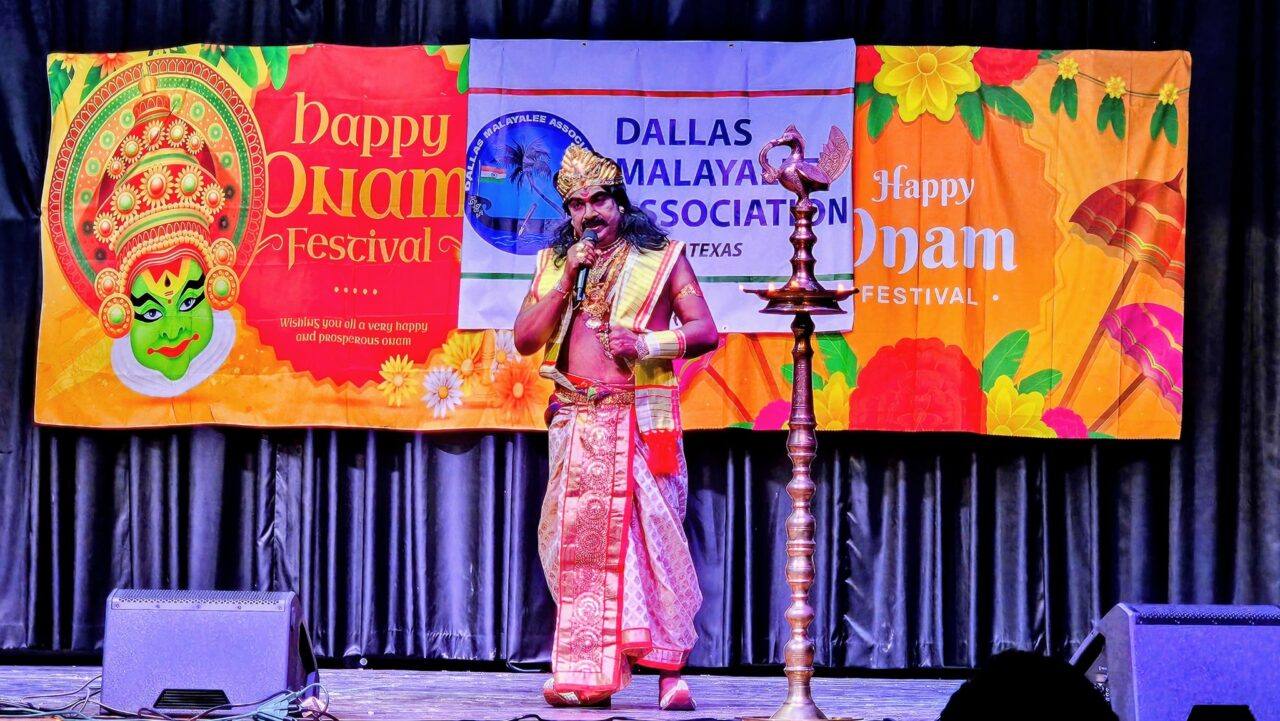

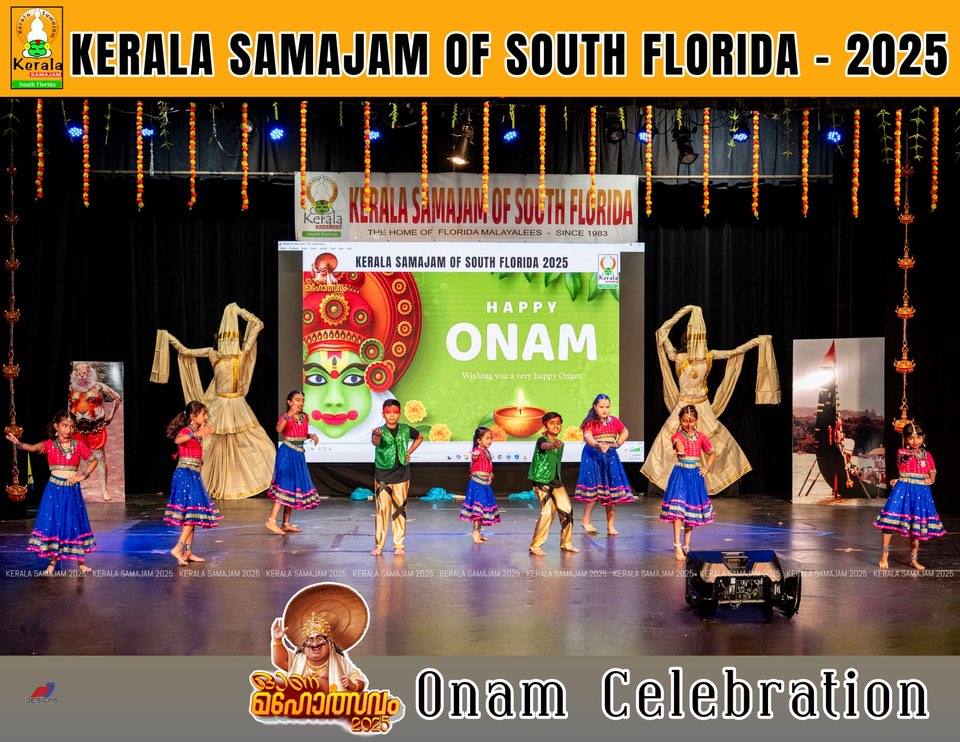

United States and Canada

SACREMENTO CALIFORNIA

DALLAS

SOUTH FLORIDA

In North America, Onam is celebrated on a grand scale. In New Jersey, “Onam Fest USA” serves Sadya to more than 3,000 people, with food prepared by volunteers over several days. In Toronto and Vancouver, convention centres are booked for Onam celebrations featuring cultural competitions and concerts. For second-generation children, these events become vital lessons in their heritage.

Parents dress them in kasavu attire, teach them Onappaattukal, and involve them in pookkalam-making, ensuring that the festival remains rooted even far from Kerala’s soil.

St. ALBERT

CHINA

Africa and Sri Lanka

In Africa, particularly in Tanzania and Kenya, Malayalees organise Pulikali performances, with local African friends joining in as tigers and hunters, creating a unique cross-cultural experience. In Sri Lanka, Tamil communities observe a simplified version of Onam with small pookkalams and Sadyas, reflecting centuries of shared cultural ties across the waters.

Europe and Australia

In Germany, Malayalee students host Onam in universities, introducing international classmates to Kerala’s cuisine and art. In Finland, Onam has a Santa Claus-like twist: Maveli appears with gifts for children, blending local culture with tradition. In Australia, cities like Melbourne and Sydney see thousands of Malayalees gathering in auditoriums and parks, staging Vallamkali replicas, Sadya, and traditional games. These celebrations often make it to local news, showcasing Kerala’s heritage to the mainstream.

The Essence Abroad

Wherever it is held, diaspora Onam has two constants: Sadya and pookkalam. Even when ash gourd is replaced with pumpkin in avial, or thumba flowers are substituted with daisies and carnations, the festival retains its essence. What changes is the audience: Onam abroad is often open to neighbours, colleagues, and friends from other communities, turning it into a celebration of intercultural exchange.

For Malayalees abroad, Onam is both a reminder of home and a statement of identity. It is the one time in the year when they recreate Kerala in their adopted lands, proving that culture is not bound by geography but carried in the heart.

How Non-Malayalees See Onam

For non-Malayalees, Onam is remarkable because of its openness. Friends, colleagues, and neighbours often join Malayalees in their celebrations, attending Sadya feasts, helping in floral designs, or dressing in kasavu attire. Many see it as a festival of generosity and inclusivity, rather than a narrowly religious ritual.

In multicultural hubs like Dubai, London, and Toronto, Onam acts as Kerala’s cultural ambassador, introducing the world to its cuisine, art, and hospitality. Outsiders often marvel at the idea of a people celebrating their ruler’s memory with such love that they hide their struggles from him. It offers a lesson in leadership, loyalty, and optimism.

Onam in Transition: Tradition Meets Modernity

Modern Transformations of Onam

Onam today is both a festival of tradition and a mirror of modern Kerala. While its roots lie in agrarian rituals and myth, the ways it is celebrated have adapted to fit contemporary lifestyles. What has remained constant is its message of unity, abundance, and joy.

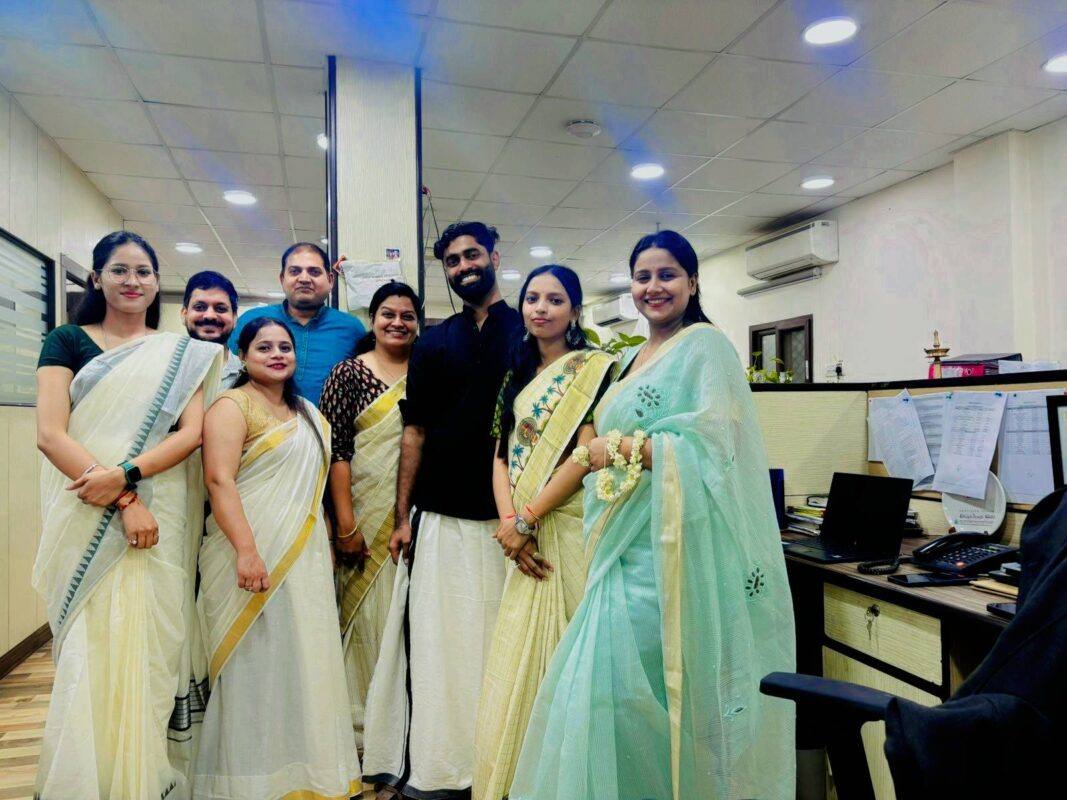

Corporate and Workplace Onams

One of the most striking modern trends is the rise of corporate Onam celebrations. IT hubs like Technopark in Thiruvananthapuram and Infopark in Kochi see employees in kasavu sarees and mundus gathering for Sadya in office canteens. Companies host pookkalam competitions, Pulikali performances, and even virtual Onam contests for employees abroad. This not only keeps culture alive in young professionals but also makes Onam a tool for workplace bonding. Multinational firms with offices in Kerala often join in, turning Onam into a global HR event.

Media, Cinema, and Entertainment

Onam has also become the biggest cultural season for Malayalam media and cinema. Television channels schedule Onam specials weeks in advance, with films, interviews, music shows, and comedy programmes. New film releases are timed to coincide with Onam, ensuring packed theatres. Blockbusters often earn a significant share of their box office collections during the Onam holidays, making it one of the most lucrative seasons for the industry. Print and digital media, too, bring out colourful supplements, highlighting recipes, stories, and festival guides.

E-Commerce and Modern Retail

Online platforms have embraced Onam in a big way. Amazon, Flipkart, and regional e-commerce portals launch “Onam sales” targeting Malayalee buyers with discounts on electronics, clothing, and jewellery. Supermarkets promote Onam combo packs of vegetables and payasam kits. Urban families, pressed for time, increasingly order Sadya home deliveries, which can range from ₹600 to ₹2,500 per plate depending on variety. This blending of tradition and convenience ensures that even those living in apartments and working long hours do not miss out.

Digital Onams

Technology has reshaped the way Malayalees connect during Onam. Families separated by distance gather on video calls to eat Sadya together virtually. Associations host online pookkalam competitions, with participants uploading photographs of their floral carpets to social media. Diaspora families live-stream Vallamkali races and Pulikali performances from Kerala. WhatsApp and Instagram are flooded with Onam greetings, Sadya pictures, and traditional attire selfies, turning the festival into a digital showcase. While some critics call this superficial, it highlights the adaptability of tradition in the internet age.

Sustainability and Eco-Conscious Onam

Modern Onam has also revived awareness of ecological traditions. Banana leaves, once taken for granted, are now appreciated as eco-friendly alternatives to plastic plates. Campaigns encourage families to use locally grown flowers rather than imported varieties, reducing carbon footprints. Farmers are incentivised to cultivate traditional vegetables for Sadya, linking Onam with sustainable agriculture. Even Pulikali troupes now use natural paints and eco-safe materials, reflecting a growing consciousness of environmental responsibility.

Balancing Past and Present

Despite these changes, Onam retains its emotional heart. The rituals may look different — a Sadya ordered through an app, a pookkalam made of roses in London, a Pulikali live-streamed to Canada — but the essence is unchanged. It is still about welcoming Mahabali, honouring abundance, and celebrating unity. In a world that is often fragmented, Onam’s ability to adapt without losing its spirit makes it both timeless and timely.

Why Does Onam Still Endure?

Onam is important to Malayalees because it is not merely a festival. It is the memory of a golden age, the celebration of harvest, the affirmation of cultural unity, and the renewal of identity. It is the story of a king who gave everything for his people and of a people who never forgot their king.

For Malayalees in Kerala and across the globe, Onam is proof that prosperity is not measured in wealth but in shared joy. It is proof that identity can survive migration and that culture can flourish even far from its soil.

In an increasingly divided world, Onam continues to symbolise harmony, inclusivity, and love between ruler and ruled. That is why, to Malayalees everywhere, Onam is not just special; it is sacred.

The essence of Onam lies in the tender bond between King Mahabali and his people. According to tradition, Mahabali is permitted to return once a year from the netherworld to visit his subjects in Kerala. The Malayalees, in turn, prepare to welcome him with splendour. They clean their homes, adorn courtyards with pookkalams, wear new clothes, and prepare elaborate feasts. Even in times of scarcity, they never allow Mahabali to see their struggles. The people believe that their king, who once gave them a land of plenty, should never feel sadness on his return. Instead, they create the illusion of prosperity, ensuring that their beloved ruler goes back reassured that his land still thrives.

This relationship is unlike any other in world mythology. It is not built on fear or obligation but on mutual affection and respect. The ruler is remembered not for power or conquest, but for justice and compassion. The ruled, in turn, display loyalty not through obedience but through love and gratitude. It is an unprecedented tale of trust, a vision of governance that modern societies can still learn from. The story of Mahabali and his people is a reminder that the ideal government is one that listens, cares, and protects, and the ideal subjects are those who respond with sincerity, unity, and pride.

“For Malayalees everywhere, Onam is not just a festival but a living memory of love, equality, and hope. It reminds us that true prosperity lies not in wealth, but in the joy we share with one another.”

— Melwyn Williams, Editor-in-Chief, The WFY Magazine

© The WFY Magazine | Melwyn Williams |

SPECIAL THANKS:

- INDIAN DIASPORA GLOBAL

- Shri KRISHNAKUMAR T N

- Shri SUDHEER THIRUNILATH