The Green Jewel Of The New Bharat

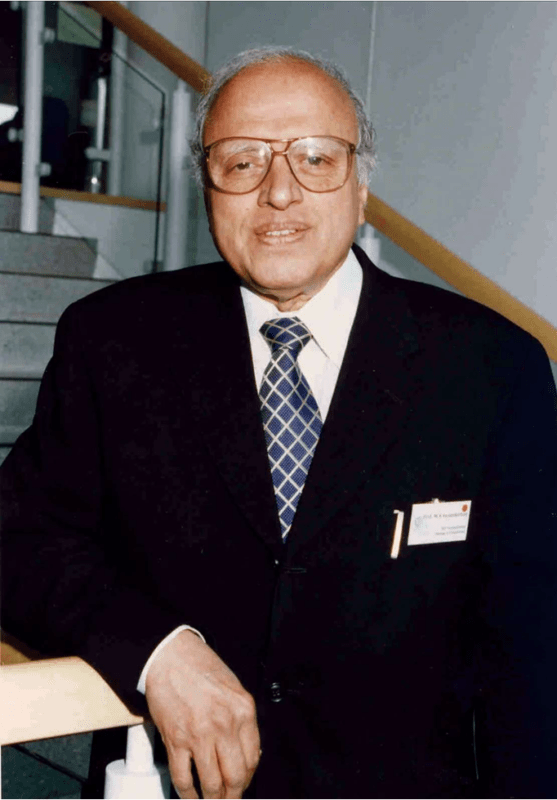

What makes M S Swaminathan so special? Why he is so important as far as India is concerned?

Swaminathan led the global green revolution. He is credited as the primary force behind the green revolution in India, leading the way in introducing high-yielding wheat and rice varieties during the 1960s to combat potential famine.

Regional Rural Bank (RRB). These banks are Indian commercial banks that operate regionally in different states of India. Established by Swaminathan, often referred to as the father of regional rural banks. There are over 10,500 branches nationwide.

Professor M. S. Swaminathan has been recognised by TIME magazine as one of the twenty most influential Asians of the 20th century, alongside Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore from India.

He has been recognised by the United Nations Environment Programme as a key figure in the field of economic ecology due to his role in the ever-green revolution movement in agriculture. Javier Perez de Cuellar, Secretary General of the United Nations, hailed him as a distinguished world scientist and living legend. He chaired the UN Science Advisory Committee established in 1980 to implement the Vienna Plan of Action. He previously held the position of Independent Chairman of the FAO Council from 1981 to 1985 and served as President of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources from 1984 to 1990.

He served as President of the World Wide Fund for Nature (India) from 1989–96. He held positions such as President of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs from 2002 to 2007, President of the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences from 1991 to 1996 and again from 2005 to 2007, and Chairman of the National Commission on Farmers from 2004 to 2006. He served as a trustee for Bibliotheca Alexandrina during its early stages.

He is truly a jewel in the crown of India, and so aptly bestowed the Bharat Ratna award on him.

Let us know more about him

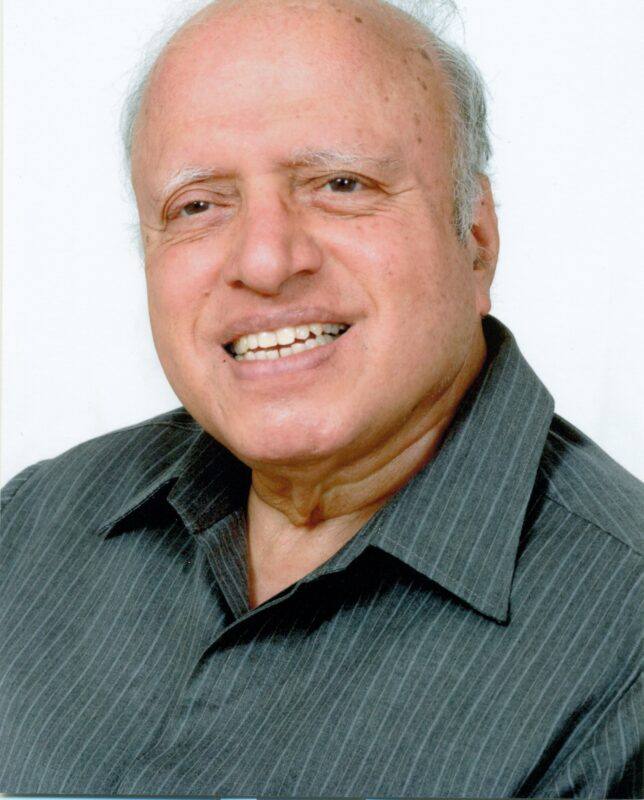

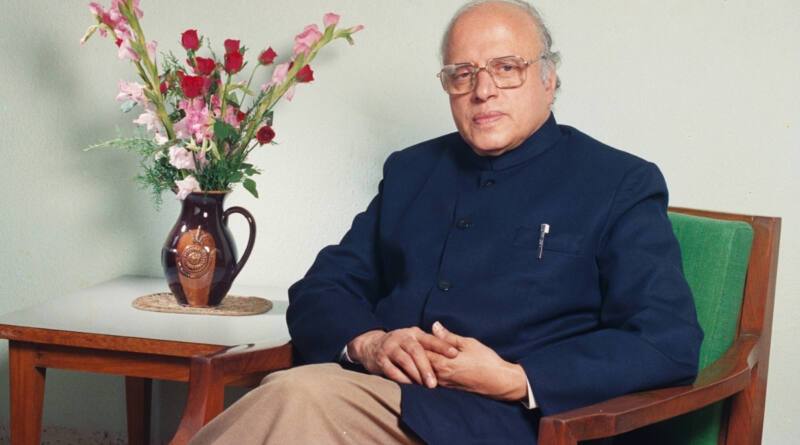

Mankombu Sambasivan Swaminathan (7 August 1925–28 September 2023) was an Indian agronomist, agricultural scientist, geneticist, administrator, and humanitarian. Swaminathan was a global leader in the green movement.

He has been dubbed the “main architect of the green revolution” in India due to his leadership and influence in introducing and creating high-yielding wheat and rice cultivars. Swaminathan and Norman Borlaug’s collaborative scientific efforts, driving a mass movement with farmers and other scientists and supported by governmental policies, spared India and Pakistan from famine-like conditions in the 1960s.

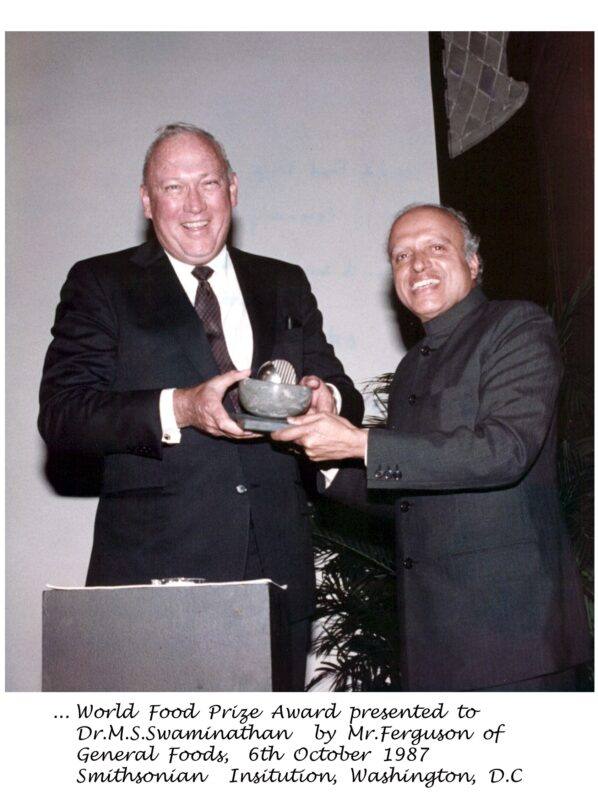

His leadership as director general of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines helped him win the first World Food Prize in 1987, which is regarded as one of agriculture’s highest awards. He is referred to as “the Father of Economic Ecology” by the UN Environment Programme.

He was awarded the Bharat Ratna, the Republic of India’s highest civilian award, for 2024.

Swaminathan contributed basic studies on potato, wheat, and rice in fields such as cytogenetics, ionising radiation, and radiosensitivity. He was the president of both the Pugwash Conferences and the International Union for Conservation of Nature. In 1999, he was one of three Indians named to Time’s list of the 20 most influential Asian personalities of the twentieth century, alongside Gandhi and Tagore. Swaminathan has earned various prizes and accolades, including the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award, the Ramon Magsaysay Award, and the Albert Einstein World Science Award. Swaminathan convened the National Commission on Farmers in 2004, which made far-reaching recommendations to overhaul India’s agricultural system. He founded the eponymous research foundation. In 1990, he coined the term “Evergreen Revolution” to characterise his vision of “productivity in perpetuity without associated ecological harm.”

He was nominated to the Indian Parliament for a single term, from 2007 to 2013. During his term, he proposed a measure to recognise women farmers in India.

Early life and education

Swaminathan was born in Kumbakonam, Madras Presidency, on August 7, 1925. He was the second son of M. K. Sambasivan, a general surgeon, and Parvati Thangammal Sambasivan. His father passed away when he was only 11 years old, and his father’s brother raised him.

Swaminathan attended a local high school before matriculating at Kumbakonam’s Catholic Little Flower High School at the age of 15. From boyhood, he was exposed to farming and farmers; his extended family cultivated rice, mangoes, and coconut, and eventually expanded into other areas such as coffee. He witnessed how crop price changes affected his family, especially the havoc that weather and pests might do to harvests and incomes.

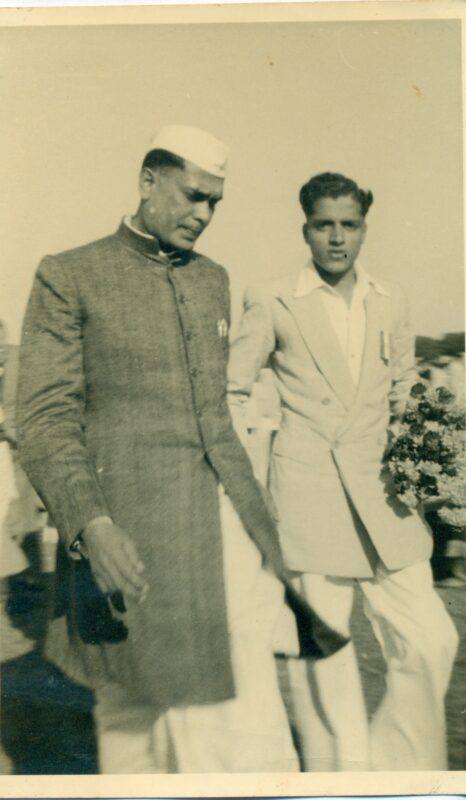

His parents urged him to study medicine. With that in mind, he began his advanced studies in zoology. However, after witnessing the effects of the Bengal famine of 1943 during World War II and rice shortages across the subcontinent, he resolved to devote his life to ensuring India had enough food. Despite his family status and being from an era when medicine and engineering were considered far more respectable, he chose agriculture.

He went on to complete his undergraduate studies in zoology at Maharaja’s College in Trivandrum, Kerala (now University College, Thiruvananthapuram at the University of Kerala). He then attended the University of Madras (Madras Agricultural College, now the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University) from 1940 to 1944, where he received a Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Sciences. During this time, he was also instructed by an agronomy professor, Cotah Ramaswami.

In 1947, he joined the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) in New Delhi to research genetics and plant breeding. In 1949, he received a postgraduate degree with good distinction in cytogenetics. His research concentrated on the genus Solanum, namely the potato. Due to social pressures, he competed in civil service tests and was selected for the Indian Police Service. At the same time, he was presented with an agricultural opportunity in the form of a UNESCO genetics fellowship in the Netherlands. He selected genetics.

The Netherlands and Europe

Swaminathan spent eight months as a UNESCO fellow at Wageningen Agricultural University’s Institute of Genetics in the Netherlands. The need for potatoes during WWII caused variations in age-old crop rotations. This resulted in golden nematode infestations in specific regions, such as reclaimed agricultural land. Swaminathan researched genetic adaptations to provide resistance to such parasites and freezing temperatures. In this regard, the research was successful. Ideologically, the university impacted his later scientific studies in India, particularly in food production. During this period, he also paid a visit to the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research in war-torn Germany; this had a profound impact on him because, a decade later, he observed how the Germans had transformed Germany, both infrastructurally and energetically.

United Kingdom

In 1950, he enrolled in the Plant Breeding Institute of the University of Cambridge School of Agriculture. In 1952, he received a Doctor of Philosophy degree for his thesis, “Species Differentiation and the Nature of Polyploidy in Certain Species of the Genus Solanum – Section Tuberarium.” The next December, he spent a week with F.L. Brayne, a former Indian Civil Service officer whose experiences in rural India impacted Swaminathan in later life.

United States of America

Swaminathan then spent fifteen months in the United States. He took a post-doctoral research associateship at the University of Wisconsin’s Laboratory of Genetics to help establish a USDA potato research station. At the time, the laboratory’s faculty included Nobel laureate Joshua Lederberg. Swaminathan’s associateship expired in December 1953, and he declined a professor position to continue making an impact back in India.

India

Swaminathan returned to India in early 1954. There was no employment available in his field, and it was only three months later that he was approached by a former professor about a temporary position as an assistant botanist at the Central Rice Research Institute in Cuttack. At Cuttack, he was part of Krishnaswami Ramiah’s indica-japonica rice hybridization programme. This experience would affect his future work with wheat. Half a year later, in October 1954, he began working as an assistant cytogeneticist at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) in New Delhi. Swaminathan criticised India’s importation of food grains, despite the fact that agriculture employed 70% of the population. More drought and famine-like conditions were developing in the country.

Swaminathan and Norman Borlaug worked together, with Borlaug touring India and delivering supplies for a variety of Mexican dwarf wheat types that were to be crossed with Japanese kinds. Initial testing on an experimental plot yielded favourable results. The crop was high-yielding, of good quality, and disease-free. Farmers were hesitant to adopt the new variety, which produced alarmingly high yields. Swaminathan was given cash in 1964 to plant tiny demonstration plots after repeatedly requesting that the new variety be demonstrated. A total of 150 demonstration plots covering one hectare were planted. The results were promising, and the farmers’ fears were alleviated. The grain was further modified in the laboratory to better suit Indian conditions. The new wheat types were grown, and in 1968 production reached 17 million metric tonnes, 5 million metric tonnes greater than the previous harvest.

In a letter to Swaminathan before collecting his Nobel Prize in 1970, Norman Borlaug credited Indian politicians, organisations, scientists, and farmers for the Green Revolution’s success. However, you, Dr. Swaminathan, deserve a lot of credit for first recognising the potential worth of the Mexican dwarfs. If this had not happened, Asia’s Green Revolution might not have occurred.

Gurdev Khush and Dilbagh Singh Athwal, two prominent Indian agronomists and geneticists, made significant contributions. In 1971, the Indian government declared that the country was self-sufficient in food production. India and Swaminathan could now address more important challenges such as food security, hunger, and nutrition. He was with IARI from 1954 to 1972.

Administrator and educator.

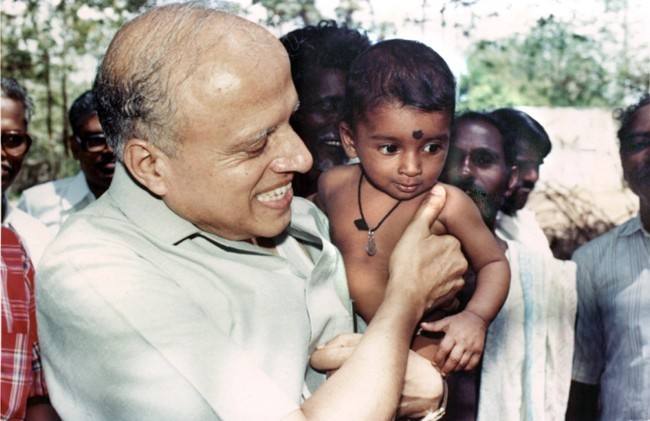

Swaminathan was appointed secretary to the Government of India and director-general of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) in 1972. In 1979, in an unusual move for a scientist, he was appointed principal secretary, a prominent position in the Indian government. The next year, he was moved to the Planning Commission. As director-general of ICAR, he promoted technical literacy by establishing institutions across India. Droughts during this time prompted him to form committees to monitor weather and crop patterns, with the ultimate goal of saving the poor from malnutrition. For the first time, women and the environment were included in India’s five-year plans following his two-year tenure at the Planning Commission.

In 1982, he was appointed the first Asian director general of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines. He remained there till 1988. During his time here, he organised an international symposium titled “Women in Rice Farming Systems.”

Swaminathan received the inaugural award for “outstanding contributions to the integration of women in development” from the Association for Women in Development in the United States. As director general, he raised awareness among rice-growing households about the importance of every element of rice production.

His leadership at IRRI helped him win the first World Food Prize. In 1984, he was elected president and vice-president of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the World Wildlife Fund, respectively.

In 1987, he received the first World Food Prize. The prize money was used to establish the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation. Swaminathan accepted the award and spoke of growing hunger despite an increased food supply. He spoke of the anxiety of sharing “power and resources” and how the aim of a world without hunger is yet unfulfilled. Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, Frank Press, President Ronald Reagan, and others praised his efforts in letters of recognition.

Swaminathan would succeed Borlaug as chair of the World Food Prize Selection Committee. He taught cytogenetics, radiation genetics, and mutant breeding at the ICAR beginning in the late 1950s. Swaminathan coached several Borlaug-Ruan interns through the Borlaug-Ruan International Internship.

Swaminathan founded the Nuclear Research Laboratory at the IARI. He contributed to and promoted the establishment of the International Crop Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics in India, the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (now Bioversity International) in Italy, and the International Council for Research in Agro-Forestry in Kenya. He contributed to the establishment and development of several institutions, as well as research support in China, Vietnam, Myanmar, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Iran, and Cambodia.

In his later years, Swaminathan co-chaired the United Nations Millennium Project on Hunger from 2002–2005 and led the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs from 2002 to 2007.[67] In 2005, Bruce Alberts, President of the United States National Academy of Sciences, said of Swaminathan: “At 80, M.S. retains all the energy and idealism of his youth, and he continues to inspire good behaviour and more idealism from millions of his fellow human beings on this Earth.” For that, we may all be grateful. Swaminathan aimed to eliminate hunger in India by 2007.

Swaminathan was the chairman of the National Commission on Farmers, which was formed in 2004. President APJ Abdul Kalam nominated Swaminathan to the Rajya Sabha in 2007. Swaminathan introduced only one law during his term, the Women Farmers’ Entitlements Law 2011, which expired. One of the goals it recommended was to recognise female farmers.

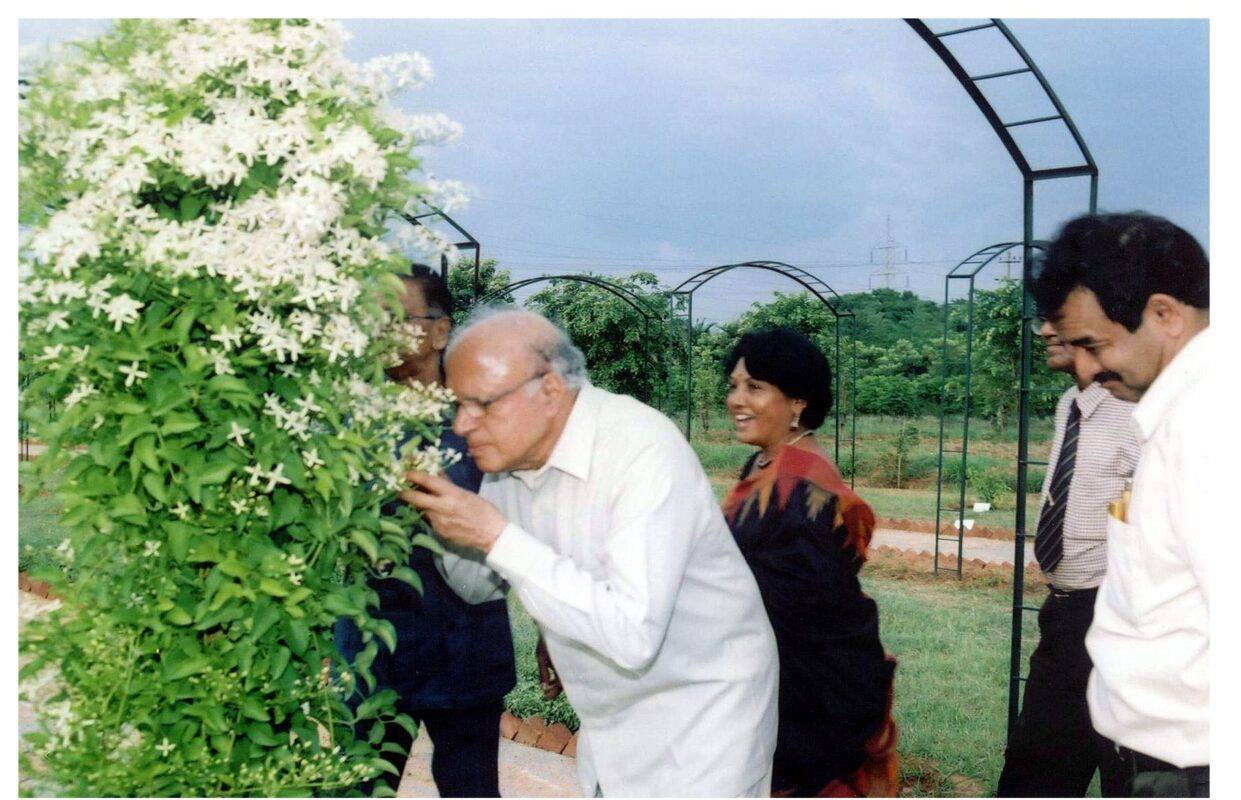

Swaminathan coined the term ‘Evergreen Revolution’, which is based on the lingering influence of the green revolution and seeks to address the continual rise in sustainable productivity that humanity requires. He refers to it as “productivity with perpetuity.”

In his later years, he was also involved in efforts aimed at closing the digital divide and bringing hunger and nutrition studies to policymakers.

Personal life and death

He married Mina Swaminathan, whom he met in 1951 while both were students at Cambridge. They lived in Chennai, Tamil Nadu. Their three daughters are Soumya Swaminathan (paediatrics), Madhura Swaminathan (economics), and Nitya Swaminathan (gender and rural development).

Gandhi and Ramana Maharshi inspired his life. Their family dedicated one-third of their 2000 acres to Vinoba Bhave’s mission. In an interview from 2011, he stated that when he was younger, he followed Swami Vivekananda.

Swaminathan died at home in Chennai on September 28, 2023, at the age of 98.

Scientific Career

Potato

Swaminathan made a significant contribution in the 1950s by explaining and analysing the origin and evolutionary processes of potatoes. He discovered its beginning as an autotetraploid and its cell division behaviour. His findings on polyploids were equally notable. Swaminathan’s 1952 thesis was based on his fundamental research on “species differentiation and the nature of polyploidy in certain species of the genus Solanum, section Tuberarium.” The result was an increased ability to transmit genes from a wild species to farmed potatoes.

His research on potatoes was valuable because of its practical use in the production of new potato cultivars. During his postdoctoral studies at Wisconsin University, he contributed to the development of a frost-resistant potato. His genetic research on potatoes, which included genetic features that regulate production and growth, was critical to enhancing productivity. His multidisciplinary systems approach perspective combined many distinct genetic elements.

Wheat

Swaminathan conducted basic studies on the cytogenetics of hexaploid wheat during the 1950s and 1960s. Swaminathan and Borlaug’s wheat and rice varieties served as the foundation for the green revolution.

Rice

Swaminathan led efforts at IRRI to develop rice with C4 carbon fixation capability, which would allow for greater photosynthesis and water usage. Swaminathan was also involved in the development of the world’s first high-yielding basmati.

Radiation Botany

Swaminathan led the IARI’s Genetics Division, which was internationally known for its mutagen research. He established a ‘Cobalt-60 Gamma Garden’ to investigate radiation mutations. Swaminathan’s connections with Homi J. Bhabha, Vikram Sarabhai, Raja Ramana, M. R. Srinivasan, and other Indian nuclear scientists enabled agricultural scientists to gain access to facilities at the Atomic Energy Establishment in Trombay (which eventually became the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre). Swaminathan’s first PhD student, A. T. Natarajan, would eventually write his thesis in this direction. One of the goals of this research was to improve plant responsiveness to fertilisers and demonstrate the practical application of crop mutations. Swaminathan’s early basic studies on the impact of radiation on cells and organisms helped lay the groundwork for future redox biology.

Rudy Rabbinge referred to Swaminathan’s 1966 report on neutron radiation in agriculture as “epoch-making” at an International Atomic Energy Agency meeting in the United States. Swaminathan and his colleagues’ findings were important to food irradiation.

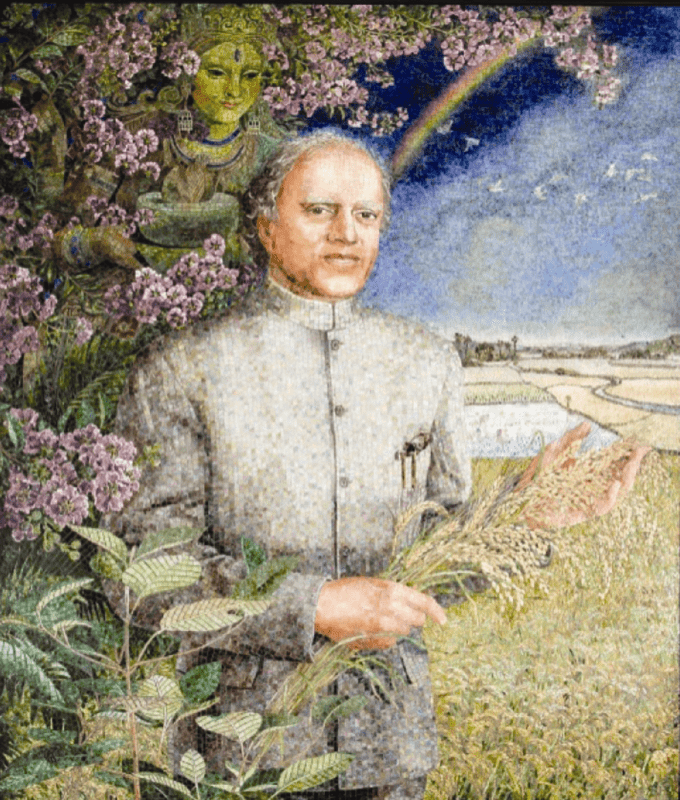

The Green Revolution

The Green Revolution is a watershed moment in agricultural history, representing great transformation and achievement. Dr. M.S. Swaminathan, known as the “father of the Green Revolution” in India, was a key figure in this transformative period. His efforts were not restricted to the development of high-yielding wheat and rice varieties but also included a holistic approach that transformed India’s agricultural landscape and food security paradigms.

Let us take a closer look at the Green Revolution:

- Dr. Swaminathan’s work helped develop and spread high-yielding crop types, including wheat and rice. These Indian-adapted cultivars considerably increased food grain yields. The introduction of these HYVs was complemented by modern agricultural practices, such as the use of fertilisers and irrigation techniques, all of which contributed to increased yields and turned India from a food-importing country to one striving for food grain self-sufficiency.

- Punjab led the way in implementing Green Revolution innovations due to its favourable climate, irrigation infrastructure, and innovative farmers. This successful model highlighted the potential of scientific agriculture and paved the way for its replication in other parts of India.

- The Green Revolution improved India’s food security and agricultural landscape by increasing grain production and lowering reliance on imports. It made a substantial contribution to maintaining food security for a fast-expanding population and stabilising food grain prices.

- Furthermore, it boosted economic growth in rural regions, but it also widened income disparities among farmers, particularly between those who could afford the new technologies and those who could not.

Expansion Beyond Wheat and Rice

While the initial emphasis was on wheat and rice, Dr. Swaminathan’s vision included a broader range of agricultural growth. Efforts were undertaken to extend the Green Revolution’s benefits to other crops and locations, with the goal of creating a more equitable and sustainable agricultural growth model.

Contributions to Agricultural R&D

Dr. Swaminathan’s contributions to agricultural research go well beyond the Green Revolution. His contributions to plant genetics and breeding resulted in more durable and productive crop varieties.

As a leader at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute and the International Rice Research Institute, he led programmes that influenced agricultural methods. Additionally, the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation reflects his dedication to sustainable agriculture and biodiversity protection.

Public recognition

In 1961, he got one of the first national prizes, the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award. Following this, he received the Padma Shri, Padma Bhushan, and Padma Vibhushan awards, as well as the H K Firodia Award, the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Award, and the Indira Gandhi Prize. As of 2016, he had won 33 national and 32 foreign honours.

On February 9, 2024, he received the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian award.

Awards and honours

- 1961: Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award

- 1965: Mendel Memorial Medal from the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences

- 1967: Padma Shri

- 1971: Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership

- 1972: Padma Bhushan

- 1986: Albert Einstein World Award for Science

- 1987: The first World Food Prize

- 1989: Padma Vibhushan

- 1991: Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement

- 1999: Indira Gandhi Prize Award

- 2000: UNESCO Gandhi Prize

- 2000: Four Freedoms Award

- 2000: Planet and Humanity Medal of the International Geographical Union

He was conferred with,

- the Order of the Golden Heart of the Philippines,

- the Order of Agricultural Merit of France,

- the Order of the Golden Ark of the Netherlands, and

- the Royal Order of Sahametrei of Cambodia.

He received the “Award for International Co-operation on Environment and Development” from China.

He received the Bharat Ratna, the Republic of India’s highest civilian award, on February 9, 2024.

Honorary Doctorates and Fellowships

Swaminathan received 84 honorary doctorates and guided several Ph.D. students. In 1970, Sardar Patel University awarded him an honorary degree; Delhi University, Banaras Hindu University, and others followed suit. He received honorary degrees from the Technical University of Berlin (1981) and the Asian Institute of Technology (1985). Swaminathan received an honorary doctorate from the University of Wisconsin in 1983. When the University of Massachusetts, Boston, awarded him a science degree, they praised his “magnificent inclusiveness of [Swaminathan’s] concerns, by nation, socioeconomic group, gender, inter-generational, and including both human and natural environments.” Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, where he earned his PhD in botany, appointed him an honorary fellow in 2014.

Swaminathan had been elected as a fellow of several Indian science academies. He had been named a fellow by 30 academies of science and society around the world, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia, Sweden, Italy, China, Bangladesh, and the European Academy of Arts, Science, and Humanities. He was a founding fellow of the World Academy of Sciences. Peru’s National Agrarian University awarded him an honorary professorship.

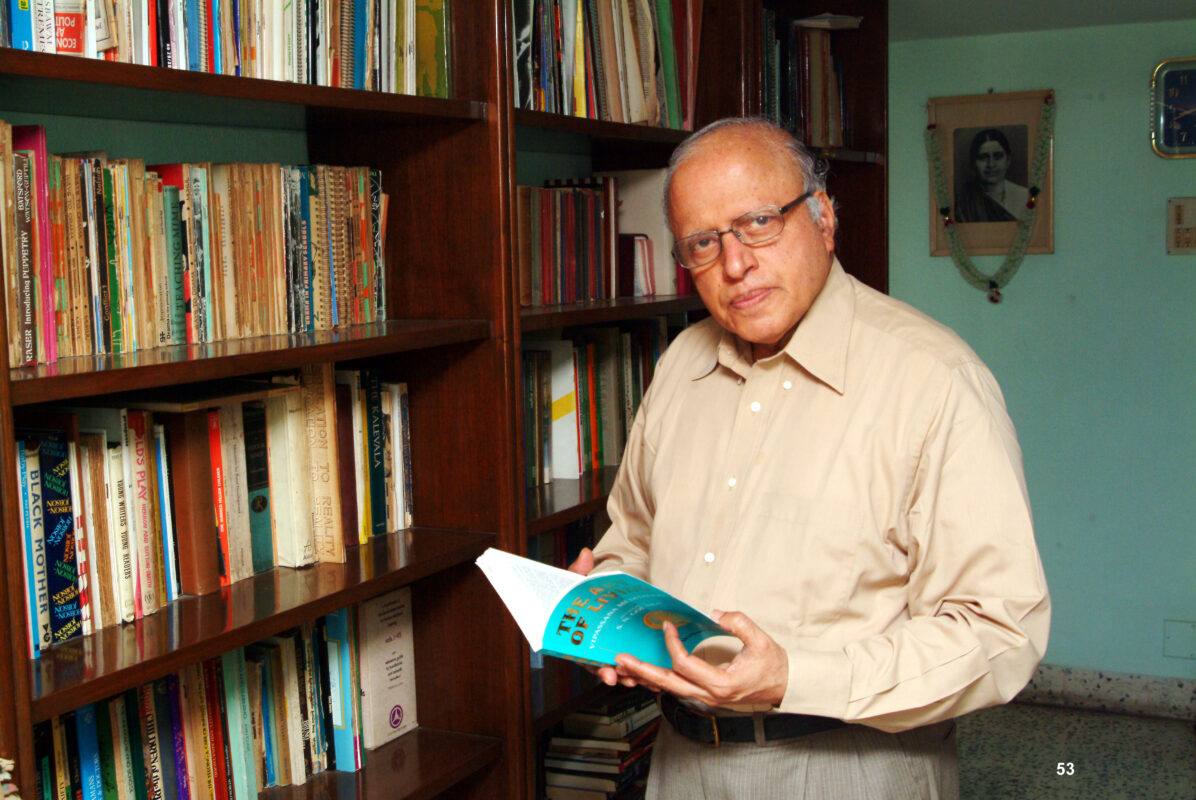

Publications

Swaminathan published 46 single-author papers between 1950 and 1980. He was the sole or first author of 155 of the 254 papers he was credited with. His scholarly works focus on agricultural improvement, cytogenetics and genetics, and phylogenetics. His most frequent publications are the Indian Journal of Genetics, Current Science, Nature, and Radiation Botany.

In addition, he has written a few books on the broad issue of his life’s work: biodiversity and sustainable agriculture for famine relief. Swaminathan’s writings, papers, conversations, and speeches contain:

In the 1970s, a scientific study in which Swaminathan and his team claimed to have generated a mutant breed of wheat by gamma irradiation of a Mexican variety (Sonora 64), resulting in Sharbati Sonora, which claimed to have a very high lysine content, sparked a big debate. The case was attributed to an error made by the laboratory assistant. The event was further complicated by the suicide of an agricultural scientist. It has been investigated as part of a larger issue in Indian agricultural studies.

Swaminathan was mentioned as a co-author in a study published in Current Science on November 25, 2018, titled ‘Modern Technologies for Sustainable Food and Nutrition Security’. A number of scientific experts attacked the essay, including K. VijayRaghavan, the main scientific adviser to the Government of India, who stated that it was “deeply flawed and full of errors.” Swaminathan argued that his contribution to the work was “extremely limited” and that he should not have been included as a co-author.

As we look into Dr. M.S. Swaminathan’s enduring legacy, we see a visionary scientist whose achievements extended beyond the laboratory and influenced the lives of millions. As we address the obstacles of the twenty-first century, his accomplishments continue to motivate the next generation of scientists and lawmakers. Dr. Swaminathan’s life and accomplishments illustrate the potential of science to benefit humanity, paving the way for sustainable agriculture and a hunger-free future.

Nice blog here! Also your site loads up very fast! What host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link to your host? I wish my site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

you are in reality a just right webmaster. The site loading velocity is incredible. It seems that you are doing any unique trick. In addition, The contents are masterwork. you have performed a wonderful task on this topic!

very nice put up, i definitely love this web site, carry on it

I discovered your blog site on google and check a few of your early posts. Continue to keep up the very good operate. I just additional up your RSS feed to my MSN News Reader. Seeking forward to reading more from you later on!…