Meet the man bringing Indian arts to the UAE

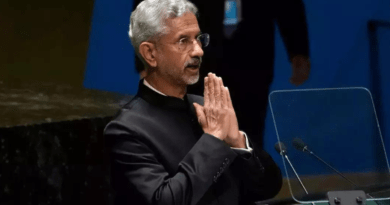

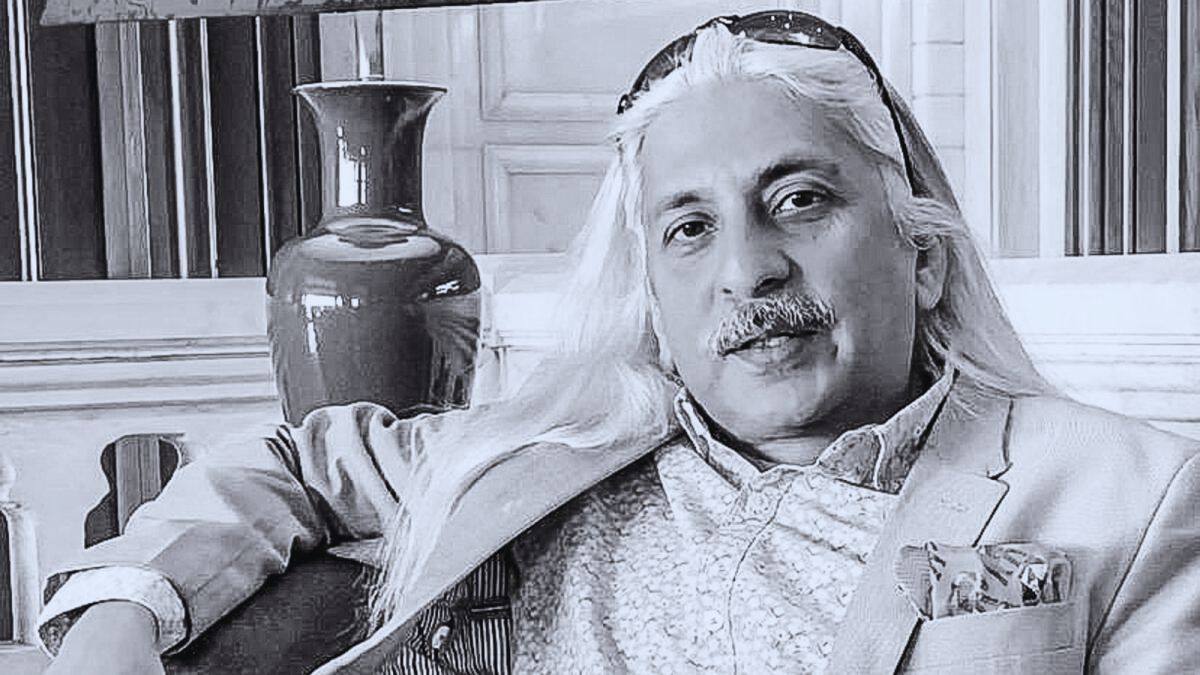

On the one hand, Sanjoy K. Roy, cultural entrepreneur and managing director of Teamwork Arts, has been working to take Indian arts and culture around the world to showcase its rich traditions and broad scope, while on the home front, the success of the Jaipur Literature Festival, one of Asia’s largest literary festivals, which Teamwork organises every year, has created a template for making literature ‘cool’ among the young.

With India by The Creek launching a new portal of cultural dialogue between India and the UAE, Roy discusses why the arts may hold the answers to our time’s most pressing questions. Edited excerpts from an interview:

What made you believe in cultural entrepreneurship? Is it difficult to monetize the arts?

I began with theatre, and Barry John served as the group’s artistic director. At the time, I was following my passion, but I also realised it was equally important to be compensated for it. When I was about to marry my wife, my future father-in-law inquired about my occupation. I replied, “I do theatre.” He insisted on knowing what my day job was until he was convinced, I worked in the theatre. He went on to say, “How will you look after my daughter?”

I responded by saying, “She is a manager in a big company, so she will be the one to look after us” (laughs). He was obviously not pleased with my response.

Television was still in its early stages at the time, and because there was no industry, the state broadcaster gave independent producers slots. Bobby Bedi, who produced Bandit Queen, contacted me, and I joined him. My partner Mohit Satyanand and I founded Teamwork in 1989, and we were primarily a film and television production company until around 1995. On those days, we’d shoot in Delhi and physically transport the tapes to Bombay before sending them to Nepal for uplinking.

Mohit had already established Friends of Music, a cultural programme that brought musicians and discerning audiences together under one roof. And we replicated a similar format for dance, featuring Kathak dancer Aditi Mangaldas and acclaimed dancer Daksha Sheth. Their work was unique and spectacular, capturing audiences’ attention. Our breakthrough came when we established our first platform at the Edinburgh Festival. Once we had that approval, things became much easier.

We realised that if you create a touring festival, you can generate revenue in the various cities you visit. We discovered an economic model by accident. There were no previous examples of this type of work being done in India.

We were not doing Broadway musicals, but rather contemporary works based on classical Indian imagery. It took some time, but we were able to multiply it in various parts of the world.

Indians living outside of India frequently associate culture with nostalgia. How does one cater to such a crowd?

When we first started, there was no sense of doing contemporary work. We were essentially presenting the arts as they were intended to be performed or showcased. When we first started pushing dance, we encountered some resistance. I remember Aditi Mangaldas saying in Edinburgh, “You’re making me dance on the streets of Edinburgh.” My Guru will suffer a heart attack.

I used to push them to look the way they did, for example, when designing costumes. When the artist listened to our feedback and observations, it was great; when they didn’t, it was difficult. But there was another side to it: dance critic Mary Brennan, who had worked for The Herald, once told me, “So, you will show certain ways in which Indians stump their feet?” We brought them to India and introduced them to the country’s rich dance tradition. I believe the fault also lay with us: we had not educated critics or peers on the essence of our culture.

Much of what we see in contemporary spaces has classical roots.

You see the Indian diaspora coming to terms with classicism, and it’s not just the first generation. People forget that Indian classical dance and music are not like instant noodles; they take years to perfect.

It’s interesting that you’re talking about artistic responsibility because there is an entire generation of young people who, according to reports, have short attention spans and thus require content to be tailored to their specific needs. How can we make art and culture more accessible to them?

It is not about accessibility, but about making arts and culture “sexy” enough for them to participate in.

We were able to address this issue at several of our festivals. At the Jaipur Literature Festival, 80% of our audience is under the age of 25. In any other literary event around the world, the average age of the audience is 50–55 years. We want young people to attend these festivals because they bring new energy to the table. When we catch them young, we can guide them away from the world of WhatsApp information.

We want them to use considered knowledge to combat ignorance and hatred. Years ago, we organised a festival in Chicago and held a workshop in a park, where the city provided us with a screen and a popcorn machine.

Africans stood on one side, Latinos on the other. While playing Monsoon Wedding or Salaam Bombay, we witnessed a woman and her baby being shot at.

We paused the movie, and I asked the audience, “Is this the type of neighbourhood you’d like to live in?” Why can’t you learn to trust each other and plan something?” They set up a neighbourhood watch, and the area became much safer.

Another example I can provide is from 10–15 years ago, when I served on the Arts Council of England’s Diversity Board. Riots had broken out, so the committee decided to meet.

I asked them to identify areas where community art spaces had been closed and map them to locations where rioting was occurring. When the reports arrived, it was an exact match.

Art is important. Because working in the arts encourages you to think outside the box. Thinking outside the box makes you a better innovator. Today, innovation is critical to realising any economy’s full potential.

Has there been a recent shift in governments’ attitudes towards the arts?

Different parts of the world respond differently to culture. In Trump’s first year, he reduced the arts budget.

A few of us were invited to argue that these budgets should not have been cut in the first place. So, one of the things I said was that if you cut this budget, you’ll only be known for gun culture. Most governments do not prioritise culture because they view it as a net expense. They do not calculate the creative sector’s contribution. In the United Kingdom, it contributes more than the energy sector. In India, it is overseen by 14 different ministries, and there has never been an inventory.

The arts provide a primary source of income for approximately 400 million people. The arts account for 3.2 percent of the global economy.

During COVID, this sector lost $2.1 trillion. So you can understand the magnitude. However, more and more cities are turning to us to start festivals. Saudi Arabia is a case in point. The arts require a combination of subsidies, sponsorship, and marketing. It will never hold the same value as football or cricket, but it is becoming increasingly important for each country to highlight its identity through culture.

How did the idea for India by the Creek come about?

We’ve been working in the Middle East for a while.

Prior to partnering with Expo 2020 Dubai, we had worked with the Abu Dhabi Book Fair and the Abu Dhabi Festival and felt there was room to do more. The delegates from these events would also attend the Jaipur Literature Festival and the Kabira Music Festival. When Expo happened, we held over 100 events there. At the time, local authorities asked us to organise an annual festival. We wanted artists from both countries to collaborate and exchange ideas.

Then Ahlaam Bolooki, CEO of the Emirates Literature Foundation, asked us to investigate the market. When we met our first partner, Dubai Economy and Tourism, they were thrilled.

They assisted us throughout and wanted us to complete this before Ramadan, and the second edition just before Diwali. Then Dubai Duty Free came on board and provided invaluable assistance. To bring the festival’s first edition to Dubai, we were ably guided and supported by our local partner, Ravi Menon, who has over three decades of professional and lived experience in Dubai.

Pre-Covid, Sheikh Nahyan bin Mubarak Al Nahyan invited me to open a new festival in Abu Dhabi, which led to some collaboration with the international festival. That sets in motion what this full-fledged offering is.

What would you say is the UAE’s overall cultural ethos?

The UAE has received a lot of attention for its Bollywood experience, and we want to show that Indian culture is more than just Bollywood. When we set up JLF Doha, we didn’t expect anyone to come, but the turnout was incredible. The Qatar National Library agreed to do this. Similarly, when we were at the Abu Dhabi Festival, it was interesting to see how eager the audience was for something different. In recent years, the region has also made significant progress in its attitudes towards people from the subcontinent.