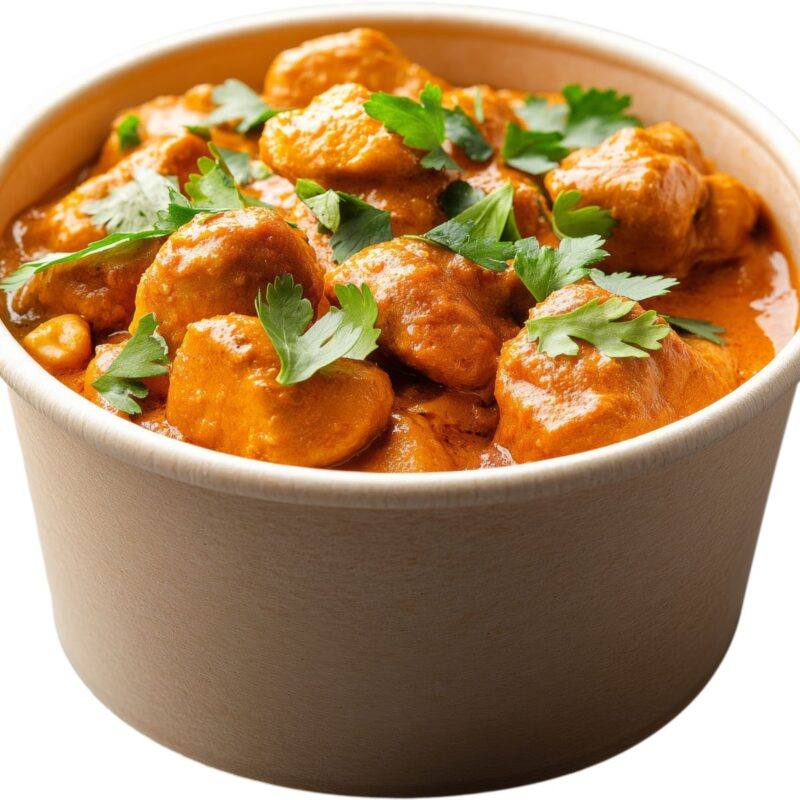

This Is The Best And Authentic Chicken Tikka Masala Reci

By WFY Bureau | Featured / From The Kitchens of India | The WFY Magazine, January 2026 Anniversary Edition

Chicken Tikka Masala: How an Immigrant Dish Became a Global Icon

A dish without a homeland, yet found everywhere

Chicken Tikka Masala does not belong to one village, one region, or even one country. It was not born in a royal kitchen or passed down through centuries of family ritual. Instead, it emerged quietly at the intersection of migration, necessity and adaptation. Today, it is one of the most recognised Indian-origin dishes in the world, served in homes, restaurants and ready-meal aisles from London to Lagos, Toronto to Tokyo.

What makes Chicken Tikka Masala remarkable is not merely its flavour, but its story. It is a dish shaped by movement. It carries within it the memory of Indian grilling traditions, the realities of immigrant life in post-war Britain, and the evolution of global taste. It represents how food travels, changes, survives and eventually becomes something larger than its origins.

For the Indian diaspora, Chicken Tikka Masala is more than a popular curry. It is a reminder that cultural identity is not static. It adapts, negotiates and finds acceptance in unexpected ways. In tracing the journey of this dish, we trace the journey of people who carried their culinary instincts across borders and reshaped global eating habits in the process.

Origins: the ancient logic of the tikka

To understand Chicken Tikka Masala, one must begin with tikka.

In the culinary traditions of North India, particularly in Punjab and the regions surrounding it, tikka refers to small pieces of meat marinated in spices and yoghurt, then cooked at high heat. This method predates modern kitchens by centuries. Long before gas stoves and electric ovens, the tandoor served as a communal cooking vessel. It produced intense heat, sealing juices quickly and imparting a smoky flavour that remains difficult to replicate.

Chicken tikka, in its original form, is dry. The marinade typically combines yoghurt with ginger, garlic, chilli, salt and aromatic spices. The purpose is both flavour and preservation. Acidic yoghurt tenderises the meat while spices act as antimicrobial agents, a practical consideration in warm climates.

This style of cooking travelled with migrants from the Indian subcontinent, especially during the mid-twentieth century when significant numbers moved to the United Kingdom from India, Pakistan and later Bangladesh. They brought with them the logic of the tandoor, even when actual tandoors were difficult to install in unfamiliar urban settings.

The first chapter of Chicken Tikka Masala is therefore not about sauce at all. It is about fire, smoke and the skill of balancing heat and spice.

Migration and the British curry house

Post-war Britain saw a steady growth of South Asian communities. Many early immigrants found employment in industrial sectors, while others turned to hospitality as a path to economic stability. By the 1960s and 1970s, curry houses had become a familiar feature of British high streets.

These establishments were not exact replicas of Indian restaurants back home. They were shaped by local tastes, ingredient availability and commercial realities. Diners unfamiliar with dry, heavily spiced dishes often preferred gravies. Sauce signalled comfort and abundance. Cream softened heat. Tomatoes added colour and sweetness.

Chicken tikka, though popular, was sometimes perceived as too dry for customers accustomed to stews and roasts. Kitchen improvisation followed. Grilled chicken was folded into a spiced tomato-based sauce, enriched with cream or butter. The result was neither traditional Indian nor entirely British. It was something new, created through dialogue between cook and customer.

This moment of adaptation is crucial. Chicken Tikka Masala was not invented as a cultural statement. It was a practical solution to a culinary problem. Yet in that solution lay the seeds of its global success.

The sauce as cultural negotiation

The defining feature of Chicken Tikka Masala is its sauce. Rich, aromatic and gently spiced, it bridges worlds.

Tomatoes, though present in Indian cooking, were not central to many pre-colonial recipes. Cream, too, was used selectively. In the British context, both became tools of translation. They made unfamiliar flavours accessible without erasing their identity entirely.

The sauce typically includes onions, tomatoes, ginger, garlic, garam masala and mild chilli, finished with cream or yoghurt. It is cooked slowly to develop depth rather than heat. The grilled chicken is added at the end, preserving its texture while absorbing the sauce.

This combination allowed curry houses to satisfy a wide audience. For immigrant cooks, it was a way to remain economically viable without abandoning their culinary roots completely. For diners, it became a gateway to Indian flavours.

Over time, Chicken Tikka Masala developed its own identity. It was no longer merely a modified chicken tikka. It was a dish in its own right, with variations across regions and households.

From Britain to the world

By the late twentieth century, Chicken Tikka Masala had crossed another threshold. It moved beyond the curry house.

The dish appeared in cookbooks, supermarket ready meals and airline menus. It became a staple at social gatherings and corporate lunches. Its popularity coincided with broader changes in global food culture, including increased travel, migration and curiosity about international cuisines.

For the Indian diaspora, particularly in countries like the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia, Chicken Tikka Masala became a familiar comfort food. It was often the dish chosen when introducing non-Indian friends to Indian flavours. Mild yet aromatic, recognisable yet distinctive, it served as a culinary ambassador.

By the early 2000s, Chicken Tikka Masala could be found in restaurants across Europe, North America, the Middle East and parts of East Asia. It adapted further, incorporating local ingredients and preferences. Some versions became sweeter, others spicier. Some leaned heavily on cream, others on tomato.

Despite these variations, the core idea remained intact: grilled spiced chicken married to a sauce designed for shared enjoyment.

Numbers that tell the story

The rise of Chicken Tikka Masala mirrors the rise of global Indian cuisine.

Market studies in the mid-2020s indicate that Indian food ranks consistently among the top five most popular international cuisines worldwide. In the United Kingdom alone, the curry industry is estimated to generate billions of pounds annually, with Chicken Tikka Masala frequently cited as one of the most ordered dishes.

Ready-meal data from Europe and North America show that Chicken Tikka Masala remains one of the highest-selling Indian-style products, outperforming many traditional regional dishes. This suggests that its appeal extends beyond restaurants into everyday home cooking.

For diaspora-owned food businesses, the dish has provided economic stability. It has supported restaurants, caterers, food manufacturers and spice suppliers. In doing so, it has played a quiet role in shaping migrant livelihoods.

Authenticity and the myth of purity

Chicken Tikka Masala often triggers debates about authenticity. Is it Indian? Is it British? Does it dilute tradition?

These questions reveal more about how we think about culture than about the dish itself. Authenticity is often imagined as fixed and ancient. In reality, cuisines have always evolved through trade, migration and adaptation.

Many foods now considered traditional were once innovations. Tomatoes, potatoes and chillies themselves arrived in the Indian subcontinent through global exchange. To deny Chicken Tikka Masala its place in culinary history is to misunderstand how history works.

For diaspora communities, adaptation is not betrayal. It is survival. Chicken Tikka Masala embodies this truth. It honours Indian techniques while acknowledging the context in which it was created.

The recipe: Authentic yet accessible Chicken Tikka Masala

What follows is a carefully balanced recipe that respects the dish’s dual heritage. It retains the integrity of the tikka while producing a sauce that is rich but not overpowering.

Ingredients (serves 4)

For the chicken tikka

- 800 g boneless chicken thighs or breast, cut into medium pieces

- 200 g thick yoghurt

- 1 tablespoon ginger paste

- 1 tablespoon garlic paste

- 1 teaspoon red chilli powder (adjust to taste)

- 1 teaspoon ground cumin

- 1 teaspoon ground coriander

- 1 teaspoon paprika

- Salt to taste

- 1 tablespoon lemon juice

- 2 tablespoons oil

For the masala sauce

- 3 tablespoons butter or ghee

- 2 tablespoons oil

- 2 large onions, finely chopped

- 2 teaspoons ginger-garlic paste

- 400 g tomatoes, pureed

- 1 teaspoon turmeric

- 1 teaspoon ground cumin

- 1 teaspoon ground coriander

- 1 teaspoon garam masala

- 150 ml fresh cream

- Salt to taste

- A small handful of fresh coriander, chopped

Method

- Marinate the chicken

Combine yoghurt, ginger, garlic, spices, salt, lemon juice and oil. Add the chicken and mix well. Cover and refrigerate for at least four hours, preferably overnight. - Cook the tikka

Preheat the oven grill or a heavy pan. Cook the marinated chicken on skewers or directly on a greased surface until lightly charred and cooked through. Set aside. - Prepare the sauce base

Heat butter and oil in a pan. Add onions and cook slowly until golden. This step is essential for sweetness and depth. - Build the masala

Add ginger-garlic paste and cook briefly. Stir in turmeric, cumin and coriander. Add tomato puree and cook until the oil begins to separate. - Bring it together

Add the grilled chicken pieces to the sauce. Simmer gently for ten minutes. Stir in cream and garam masala. Adjust seasoning. - Finish and serve

Garnish with fresh coriander. Serve with naan, roti or plain rice.

This version avoids excessive sweetness and allows the smokiness of the tikka to remain present.

Why this dish matters?

Chicken Tikka Masala matters because it tells a larger story about food and belonging.

For immigrants, cooking is often one of the few spaces where control remains. It is where memory is preserved and identity negotiated. When dishes like Chicken Tikka Masala gain acceptance, they do more than please the palate. They create cultural bridges.

For host societies, embracing such food is often the first step towards recognising the people behind it. Curry houses became informal meeting points, where unfamiliar cultures felt less distant.

For younger generations of the diaspora, Chicken Tikka Masala can be both a comfort and a conversation starter. It may not resemble the food cooked by grandparents, yet it reflects a lived reality of hybridity.

Food as memory, survival and dialogue

The global success of Chicken Tikka Masala underscores a fundamental truth. Food is not static. It travels with people, adapts to circumstances and carries stories across borders.

In an era when migration is often discussed in economic or political terms, dishes like Chicken Tikka Masala offer a quieter narrative. They show how cultures blend not through force, but through everyday choices. Through hunger. Through hospitality.

What began as an improvised solution in a small kitchen has become a shared global experience. That journey is worth celebrating.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for editorial and cultural exploration purposes only. Recipes and historical interpretations reflect commonly accepted culinary practices and publicly available information as of 31 December 2025. Variations exist across regions and households. Readers are encouraged to adapt recipes to their dietary needs and preferences.