This Is The Remarkable World Of Indian Classical Music

By Kavya Patel | Art and Culture | WFY Magazine October Edition

India’s classical music is not just art; it is mathematics, philosophy and spirituality woven into sound.

A prelude from a London living room

On a quiet Sunday afternoon in Southall, a girl tunes a small electronic box until a mellow Sa fills the room. Her grandmother calls it the thread that holds a raga together. The girl counts under her breath, ‘Ta ka dhi mi’, while her teacher on a video call from Chennai asks for a slow phrase in Kalyani. A smartphone balances on a pile of books, a tanpura app hums, and a mridangam track keeps time. There is nothing exotic about this scene. It is a slice of the Indian diaspora’s everyday life. It is also a window into a civilisation where sound is science, prayer and poetry at once.

We often praise Indian classical music as heritage. The truth is more ambitious. It is a system where mathematics organises melody, where philosophy gives it meaning, and where spiritual practice turns it into experience. Treat it only as art, and we miss its depth. Treat it only as tradition, and we miss its innovation. This feature follows the architecture of that depth, then asks a hard question for the diaspora: how do we keep a living science alive in a noisy digital market?

I. The grammar of infinity

Indian music rests on a simple alphabet of seven notes: Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni. Yet within this simplicity lies a vast combinatorial universe.

- Intervals and ratios. Sa to Pa forms a pure fifth, a frequency ratio of 3:2. Sa to Ma is a fourth at 4:3. The octave, Sa to higher Sa, is 2:1. Ancient texts speak of twenty-two microtonal shades called shrutis that lie within the octave. Whether one accepts all twenty-two in practice or treats them as theoretical, the idea is clear. Pitch in this tradition is a continuum, not a grid.

- Movable tonic. Unlike the tempered piano, where A is anchored at 440 hertz, the Indian system treats Sa as movable. A vocalist chooses a comfortable Sa, the ensemble follows, and the tanpura lays a living acoustic benchmark. This single decision keeps the music human-centred. The instrument bends to the body, never the other way around.

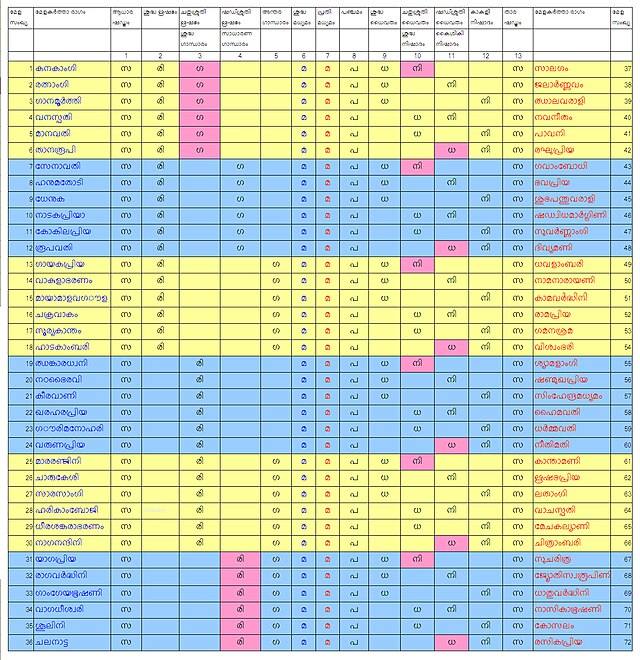

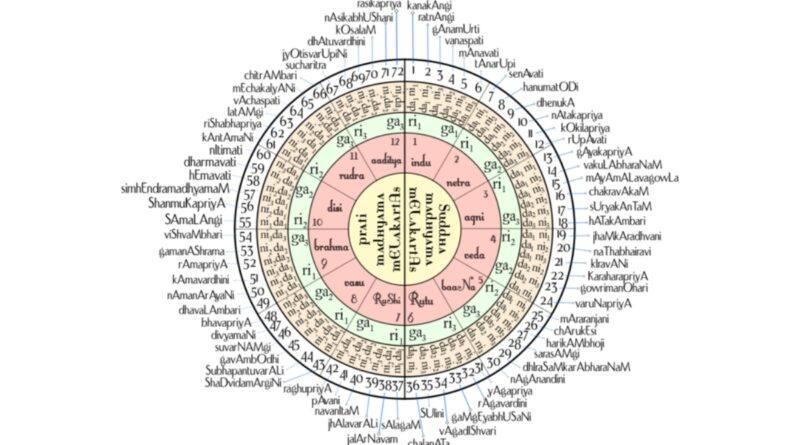

- Heptatonic parents. Carnatic music organises scales through the Melakarta framework. There are seventy-two parent ragas created by systematic choices of swara variants. Each parent raga is sampurna, with seven notes in both ascent and descent. The first thirty-six use the natural Ma; the next thirty-six use the sharpened Ma. These parents are grouped into twelve chakras, each holding six ragas that differ by specific Re, Ga, Dha and Ni positions. From this lattice, thousands of derived ragas emerge.

- Permitted motion. A raga is not a scale alone. It is a grammar of motion. Ragas carry arohana and avarohana paths, resting notes, characteristic phrases, and intonational bends that give life to swaras. The same seven notes can narrate a different story when the grammar changes.

If this sounds mathematical, it is. But it is the mathematics of nature rather than a rigid timetable. Ratios anchor purity, permutations expand possibility, and grammar protects identity.

II. Rhythm that thinks

If pitch is a canvas, rhythm is architecture. South Indian rhythm, tala, is a language of counts and shapes. The Suladi system describes families of talas whose building blocks are laghu, dhruta and anudhruta. A laghu holds 3, 4, 5, 7 or 9 beats depending on the chosen jati. Add the other units, and you get frameworks such as Adi, Misra Chapu, Rupaka and Khanda Triputa. A simple Adi tala can be felt as a clean eight or subdivided to hold dizzying designs.

Percussionists speak in syllables. Ta ka dhi mi, ta ki ta, and ta ka ta ri ki ta survive not as jargon but as mental algebra. In Hindustani music, the tihai is a three-fold cadence whose last stroke lands on the sam, the home beat. If the cadence is five beats long and the cycle has sixteen, the performer must calculate the exact starting point so that 3 × 5 plus the intervening gaps end precisely on sam. It is number theory in real time.

Rhythm in this culture is not a domestic servant counting metronome clicks. It is a thinking partner. Every concert hall in the diaspora has seen this dance, the mridangam player trading ideas with the vocalist, the tabla artist constructing a tihai while the audience leans forward and counts along on fingers and hearts.

III. Why philosophy sits at the centre

The phrase ‘Nada Brahma’, sound as a face of the absolute, is more than poetry. It explains why the tradition treats music as a discipline of attention. A raga unfolds in time. The listener learns to inhabit the present fully because a note bent wrongly cannot be edited later.

Philosophy here is not a syllabus. It is a way of listening.

- Rasa and raga. Ragas are associated with emotional colours called ‘rasa’. Yaman can feel luminous and hopeful, Bhairavi reflective, and Todi austere and inward. The mapping is not a dogma. It is a conversation between melody and memory built over centuries.

- Time theory. Hindustani music links many ragas to times of day or seasons. Morning ragas emphasise certain pitches and intervals that awaken, and night ragas those that soothe. Carnatic practice is less prescriptive yet recognises the same psychological currents. This is music as chronobiology.

- Silence as grammar. Indian music holds silence with care. A pause before resolving to Pa is as meaningful as the note itself. The tanpura continues to sound during the pause, which means silence is never emptiness. It is pregnant, like the space between breaths in pranayama.

Philosophy, then, is not a garnish added after the piece is cooked. It is the recipe.

IV. The spiritual lineages

Dhrupad grew from temple and court, devotional yet rigorous. Khayal absorbed Sufi openness and became a theatre of imagination. In the South, Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar and Syama Sastri, the Trinity, tied musical invention to devotion without reducing it to a slogan. Bhakti did not narrow the art. It widened it.

For diaspora families who pray in community halls, the continuity is clear. A bhajan evening in Dubai, a veena recital in Kuala Lumpur, or a dhrupad workshop in Leicester are not only concerts. They are acts of cultural remembering where song, language and ritual melt into each other. When elders say music kept their children rooted, they mean it literally. Form sits on feeling.

V. The science that modernity rediscovers

Neuroscience shows that long-term training in pitch and rhythm reshapes auditory and motor areas of the brain. Musicians demonstrate superior pitch discrimination and timing. Breath-based practice lowers stress markers. None of this is a surprise to a tradition that twinned music with yoga and meditation. The tampura’s overtone ladder mirrors the harmonic series. The drone is a continuous biofeedback system that trains attention.

In hospitals from Bengaluru to Boston, clinicians now explore raga-based music therapy for anxiety, stroke rehabilitation and palliative care. Preliminary studies suggest that specific combinations of tempo and interval can shift arousal and mood. It is early; rigorous evidence will take time, and sweeping claims should be avoided. What matters is a renewed scientific curiosity that meets tradition halfway.

VI. The diaspora ecology: strength and strain

There are more than 35 million people of Indian origin spread across the world. Many live in cities where weeknight traffic and weekend chores compete directly with concertgoing. Yet diaspora sabhas, community music schools and house concerts have kept the ecosystem alive.

Strengths

- Education. Zoom bridged continents. Gurus now teach students in Sydney, Nairobi and New Jersey from their homes in Chennai or Pune. Examinations from Indian boards reach diaspora candidates, and children collect graded certificates with pride.

- Community funding. Families sponsor tours, host artists, and underwrite halls. The goodwill is real and generous.

- Hybrid pedagogy. A teenager can practise with a digital tanpura, submit assignments by voice note and learn tala with a metronome app. The once solitary riyaaz has become socially connective.

Strains

- Accompanist scarcity. Many cities have more vocal students than trained accompanists on violin, harmonium, mridangam and tabla. A promising student can struggle to find a partner who matches phrasing and sensitivity.

- Visa and touring bottlenecks. Immigration rules often force concert organisers to juggle dates or abandon plans. Last-minute cancellations are common, and the financial risk sits with volunteers.

- Instrument logistics. Mridangams with animal skins trigger customs delays. Repairs for veenas or sitars require specialist luthiers who are thinly spread outside India.

- Attention economics. Streaming platforms promote short clips and algorithmic novelty. Slow unfolding forms suffer in such marketplaces. Many young listeners discover ragas through film songs before they ever hear a full alap or niraval.

The question for a community magazine like ours is practical. Where do we intervene?

VII. Five problems that need solutions, and what those solutions could look like

1. Documentation is scattered and inconsistent.

A single raga can carry multiple notations, variant phrases and spellings. Valuable archives live on personal hard drives, not in public libraries. When a teacher retires or passes away, decades of knowledge are at risk of fading.

What to do

- Build a diaspora-run open catalogue of ragas with audio examples, permitted phrases and tala breakdowns, all peer reviewed. Keep it non-commercial and dignified.

- Encourage artists to deposit teaching materials in national libraries or community repositories with clear rights.

2. Learning stalls at the intermediate level

Children often study for a few graded exams, then pause during university or early career years, and never return. The community loses talent in this long middle.

What to do

- Create paid ensemble fellowships in diaspora cities that pair intermediate students with accompanists for a season, culminating in public recitals.

- Introduce mentorship circles where a senior artist guides four or five young adults for a fixed year, with goals, reading lists and a performance plan.

3. Accompanists do not get the same respect.

A violinist or tablist is sometimes treated as a support act rather than a co-creator. Fees and publicity reflect that imbalance. Over time, fewer students choose the accompanist path.

What to do

- Publish transparent fee bands for organisers to adopt, with parity thresholds.

- Programme concert series built around accompanist artistry, for example, tani avartanam showcases or jhala masterclasses, so that the craft is seen at the centre.

4. Instruments and repairs are a headache.

A broken bridge on a veena can end a season. Many players carry instruments across continents with a prayer.

What to do

- Build regional instrument hubs. A sabha in each diaspora cluster could maintain a pool of quality tanpuras, mridangams and veenas for emergency loans and contract luthiers for scheduled service camps twice a year.

- Encourage artists travelling from India to partner with these hubs for masterclasses on maintenance, stringing and skin care.

5. Young audiences need entry points.

A two-hour alap can be heaven for the initiated but a steep hill for a newcomer. Without on-ramps, the form risks becoming a private language.

What to do

- Curate one-hour introduction concerts with spoken demonstrations. Show how a raga transforms a plain scale into a grammar. Explain a tihai on stage.

- Pair classical artists with folk or jazz musicians for dialogue evenings that respect form, not fusion for spectacle.

VIII. The Melakarta as both science and map

Carnatic musicians often call the seventy-two parents the periodic table of melody. The comparison is not fanciful.

- Twelve chakras. Each chakra groups six ragas distinguished by how the second and third notes, and later the sixth and seventh, are chosen.

- Two halves. The first half uses the natural Ma; the second half, the sharpened Ma.

- Naming by number. The Katapayadi system encodes numbers into syllables so that a raga’s name carries its index silently. For students, this becomes a memory aid and a puzzle at once.

The beauty is not only architecture. It is how the architecture births character. Kanakangi, the first, feels stark and ancient. Mayamalavagowla, the fifteenth, is a familiar teaching parent whose symmetric shape calms a beginner’s fingers. Kalyani, the sixty-fifth, is luminous and spacious. Rasikapriya, the seventy-second, is a bright gateway to modern imagination. The diagram you asked us to recreate for this issue, the circular Melakarta wheel, is not just a chart. It is a philosophy of order that invites play.

IX. Hindustani frames, cousins across a river

If Carnatic music builds with seventy-two parents, Hindustani uses ten primary thaats such as Bilawal, Kalyan, Khamaj, Bhairav and Todi. These are scale templates rather than strict parents. Ragas often bend away from them, carrying asymmetric movements, zigzags, foreign phrases and time associations. What unites the two systems is method. Both respect grammar, both expect improvisation to speak the grammar, and both prize the human voice as the teacher of intonation.

For the diaspora listener who grew up on film music, thaats and parents provide orientation. Hear how Yaman and Kalyani, cousins across systems, share a bright Ma and Ni but differ in treatment. Listen to Bhairavi on a quiet morning and then to Hanumatodi, and feel the same ancient gravity in different dialects.

X. Money, markets and fairness

We love to call our arts priceless, which is a romantic way of refusing to count. Counting matters, because artists pay rent. The economics of a diaspora concert are simple. Hall hire, artist travel and accommodation, sound reinforcement, publicity, accompanist fees and a safety margin need to be covered by tickets or sponsorship. When organisers underprice tickets to chase packed halls, an unhealthy bargain follows. Artists accept low fees for visibility. Accompanists accept less for the same reason. The next generation sees the numbers and chooses another path.

A healthy ecology speaks the language of budgets without embarrassment. Pay fairly, publish ranges, reward rehearsal, and invest in documentation. When the numbers align with values, culture survives.

XI. Learning to listen

If there is one habit that will carry the music forward, it is not more practising alone. It is listening with attention. The diaspora has access to a century of recordings, from 78-rpm rare cuts to today’s high-resolution videos. Yet algorithmic playlists flatten time, offering snippets rather than journeys.

Build listening clubs where members pick an alap to study each month. Invite older rasikas to narrate how a GNB or Bhimsen Joshi concert changed their ears. Sit quietly with friends and hear one full raga without reaching for the phone. This is not nostalgia. It is training for attention, the precondition for joy in this art.

XII. A field guide for families

A family that wants to set up a durable musical life in the diaspora can do five things this year.

- Choose a weekly listening hour at home. No screens, only sound. Share notes in a notebook that will become a family memory.

- Support accompanist education. If your child learns voice, encourage a sibling or friend to learn violin or tabla. Communities are built in pairs.

- Volunteer for documentation. Offer to record high-quality audio from the front row for your local sabha with the artist’s permission, edit it properly, and hand it back with clean metadata.

- Join a maintenance day. Help your sabha inventory microphones, cables, stands and tanpuras. The boring work is the backbone.

- Fund one experiment each year. Commission an evening of lecture demonstration for newcomers, or a workshop on raga grammar for teenagers. Publish the recordings freely.

None of this needs deep pockets. It needs care.

XIII. The question of purity and change

Is fusion a threat? The debate returns every few years. A simpler way to think is this. A raga has an identity, like a language. If the grammar is honoured, collaboration can enrich. If grammar is ignored, the result may still be pleasant, but it is another language. Both can coexist, as long as we name them clearly.

Artists have always borrowed and adapted. The violin was once a foreigner in Carnatic music and is now a native. The harmonium fought for legitimacy and won a patient place in the North. The mridangam’s cross-rhythms have influenced global drumming. Change is a river. Purity is not the absence of change. It is fidelity to grammar while crossing new bridges.

XIV. Towards a living future

The Indian diaspora has the advantage of distance. From London or Lagos, one can see the tradition as a whole. We can also see the gaps. The way forward is not another slogan about heritage. It is practical dignity. Pay artists on time. Teach children to count cycles before they chase stage time. Treat a recording as literature, not as a disposable file. Ask governments for easier cultural visas and declare instruments as intangible heritage needing facilitation at borders. Support serious scholarship that links mathematics to musical pedagogy, so that a teenager who loves numbers can find a doorway into raga.

The line that opened this article remains our thesis. Indian classical music is not just art. It is mathematics shaping melody, philosophy guiding interpretation and spirituality deepening experience. When the diaspora understands this trinity and plans with it in mind, we do more than preserve a tradition. We renew it.

A clear, thought-provoking account of why this music is a total knowledge system, and practical steps for keeping it alive wherever Indians live. If your home already hums with a tanpura, may this issue deepen your listening. If you are new to the form, begin with one raga and one tala this month. Let attention do the rest.