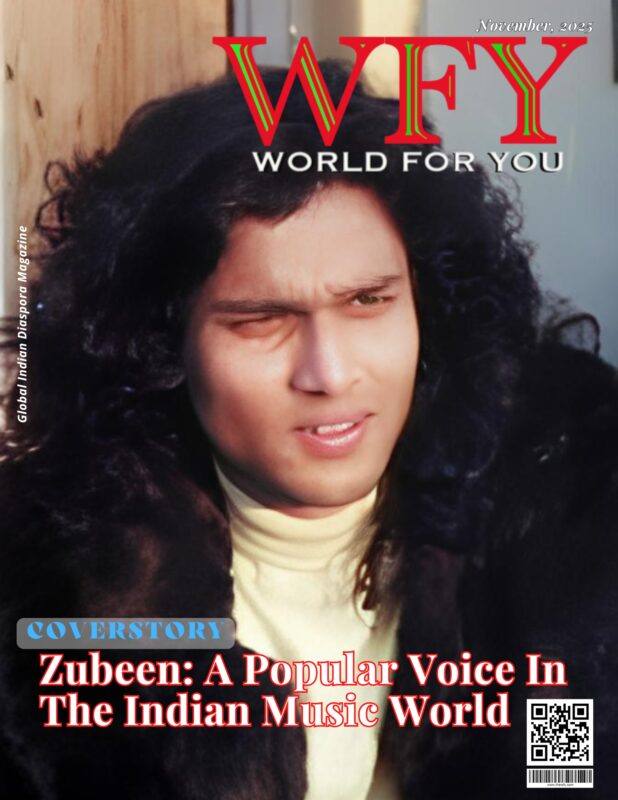

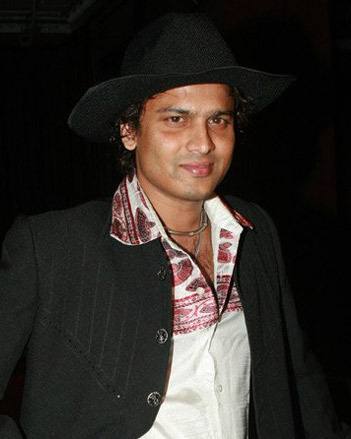

Zubeen: A Popular Voice In The Indian Music World

By Wynona M | Cover Story | The WFY Magazine, November 2025 Edition

The Day Assam Fell Silent

On the afternoon of 19 September 2025, Assam fell still. Radios, cafés, and classroom corridors echoed with one impossible headline; Zubeen Garg was gone. The voice that had narrated the hopes and heartbreaks of a generation had vanished somewhere between the blue of the Singapore sea and the memory of his homeland. He was fifty-two.

Television anchors trembled mid-sentence. Students abandoned classrooms. In Guwahati, the loudspeakers that once roared his Bihu hits now replayed them as elegies. Within hours the streets filled, candles appeared at street corners, and “Aamar loratu gol – our son is gone” became the cry of a people.

When his body returned home, over a million mourners lined the thirty-one-kilometre stretch from the airport to Kamarkuchi. Offices closed, markets shut, and traffic halted. Assam was not mourning a celebrity; it was burying a part of itself.

The Voice that Became a Mirror

To grasp why grief spread like a tide, one must understand what Zubeen meant to the Assamese soul. He was more than a playback singer. He was a mirror reflecting their wounds, humour, and stubborn joy.

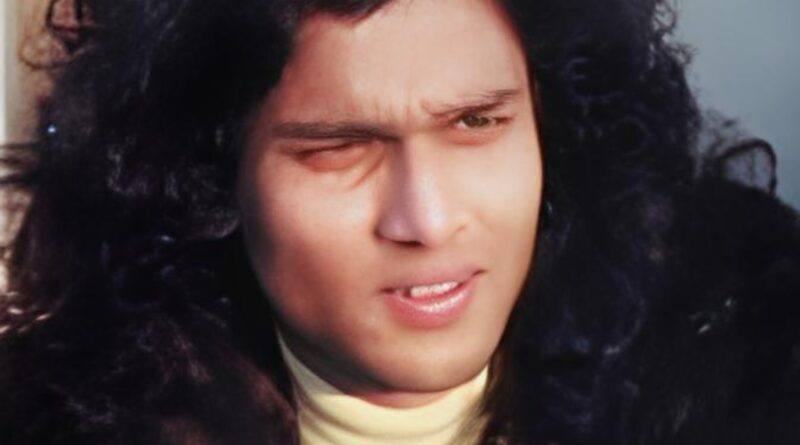

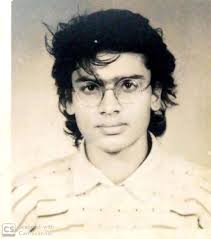

Born 18 November 1972 in Tura, Meghalaya, Zubeen Borthakur grew up in a home where art was everyday air. His father, poet-magistrate Mohini Mohan Borthakur, wrote under the name Kapil Thakur. His mother, Ily Borthakur, a noted singer, became his first teacher. By three he was performing folk tunes. Eleven years of tabla training under Pandit Robin Banerjee and folk guidance from Guru Ramani Rai gave him discipline and range.

He studied in Carmel School (Jorhat), Karimganj High School and Bijni Bandhab High School before completing matriculation at Tamulpur Higher Secondary School in 1989. Science courses followed at J. B. College and B. Borooah College, but classrooms could not contain his hunger. He left college to live for music.

In 1992 he recorded his first Assamese album Anamika, and that slim cassette became a revolution. Assam was still scarred by insurgency; gatherings were silent and cultural confidence low. Out of that silence came this boy’s voice – rough, searching, honest. He sang of love and loss in the language of his people, giving them something they had forgotten: hope.

A Singer of the common man

Zubeen never sang from ivory towers. His music smelled of wet earth, bus stations, and tea stalls. Listeners saw him sitting on pavements after concerts, sipping chai with fans, joking with buskers. He made fame look friendly.

Assam in the 1990s bled through unrest and censorship. Many artists emigrated; he stayed. He sang through curfews, travelled to remote fairs, recorded on borrowed microphones. That courage made him a symbol of resilience.

He never sought political power yet never shied from moral stands. When injustice appeared, he spoke – fearlessly but never for a party. That distance kept his credibility intact. “People first,” he said through his deeds.

His imperfections – temper, impulsiveness, public scoldings – only made him more real. Fans forgave because he was transparent. When he stumbled, they clapped louder. His humanity became their comfort.

A Rebel with No Party

Fame often tames, but Zubeen remained gloriously untamed. He refused to join political camps, yet his conscience was political. During the Citizenship Amendment Act protests, he walked with students urging peace yet demanding justice. His song Politics Nokoriba Bandhu (“Don’t do politics, my friend”) became the anthem of dissent wrapped in compassion.

He questioned animal sacrifice at Kamakhya, denounced caste privilege, and declared himself “free from religion.” To many that sounded radical; to Assam it sounded honest. They believed his intent because his life proved it. His faith was humanity.

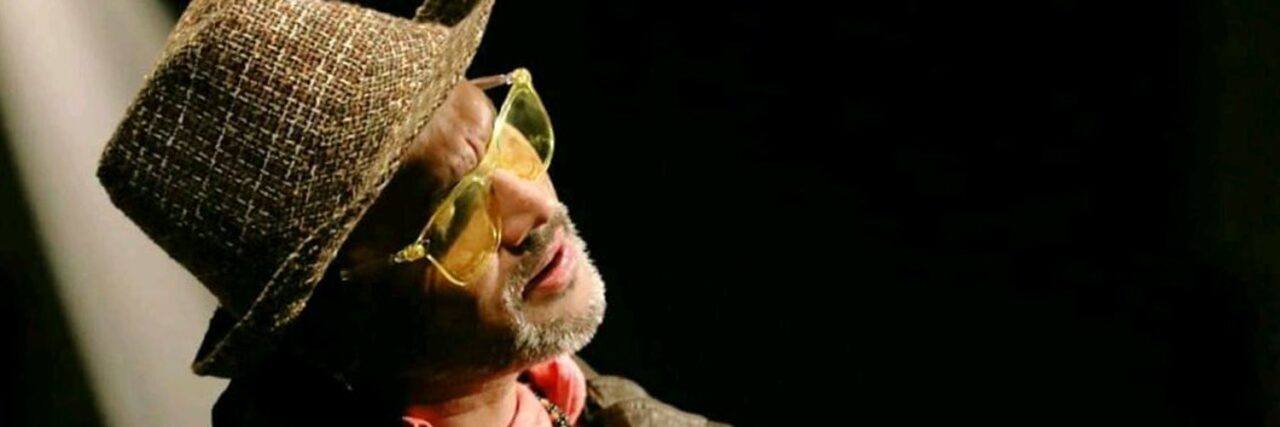

The Multilingual Phenomenon

Across thirty-three years he recorded more than 38,000 songs in over forty languages – Assamese, Bengali, Hindi, Bodo, Nepali, Tamil, Bishnupriya Manipuri, and more. Few singers anywhere matched that linguistic range.

Albums such as Maya, Asha, Pakhi and Chandni Raat defined modern Assamese pop. Chandni Raat (1996) even reached Channel V’s national charts. A decade later, Ya Ali from Gangster (2006) catapulted him to all-India fame, earning the GIFA Award for Best Playback Singer. Yet instead of settling in Mumbai, he returned home. He used every national cheque to fund Assamese films and new musicians.

He wanted to prove that a voice from the Northeast could resonate across India without losing its accent. And he did.

Cinema and Zubeen

When melodies could no longer hold his stories, Zubeen turned to cinema. Acting and directing let him explore social truths that songs alone could not contain.

He debuted with Tumi Mor Matho Mor (2000) and went on to create a new Assamese film grammar with Mon Jaai (2008), Rodor Sithi (2014), Gaane Ki Aane (2016), Mission China (2017), Kanchanjangha (2019), Dr. Bezbarua 2 (2023) and Sikaar (2024).

Mission China earned around ₹6 crore, then Kanchanjangha broke its record with ₹7 crore – historic numbers for regional cinema. His upcoming project Roi Roi Binale was poised to be Assam’s first Dolby Atmos film before fate intervened.

Through film he portrayed corruption, migration, and the erosion of innocence. To the youth, he became proof that Assamese cinema could compete with any industry in craft and confidence.

A One-Man Industry

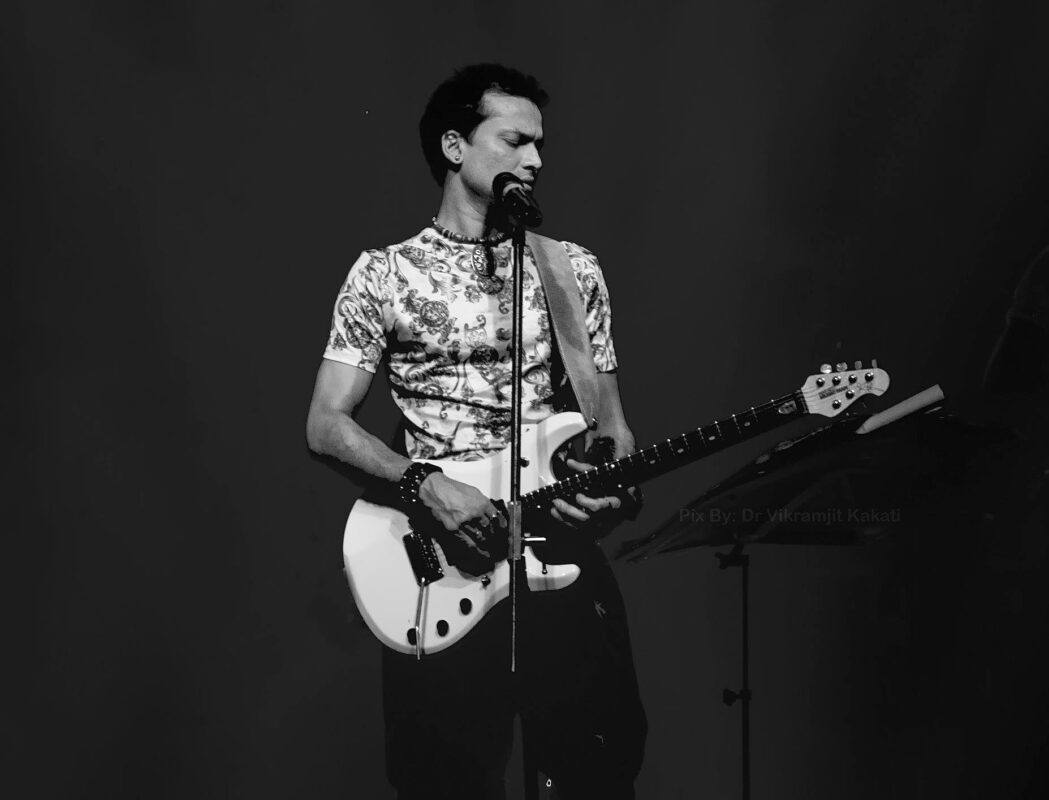

By the 2020s Zubeen had evolved into an institution. He wrote scripts, composed, sang, produced albums, acted in over thirty films, directed four, and mentored countless artists. He played a dozen instruments with equal ease.

Comparisons with Bhupen Hazarika were inevitable, yet he dismissed them kindly. “I am continuing their journey, not replacing them,” he once remarked in an interview.

Through his Kalaguru Artiste Foundation, he created employment for musicians, editors, and camera crews. He decentralised fame: “Let them earn, let them shine.”

During floods he donated his concert revenue. In 2021 he offered his Guwahati house as a COVID-19 care centre. His philanthropy rarely reached headlines because he disliked spectacle. For him, kindness was private duty.

Heart, Humanity and Honour

Zubeen’s moral compass was simple – art must serve life. He renounced his sacred thread, rejected caste titles, and urged youth to question superstition. He believed faith should comfort, not divide.

His compassion extended to animals; he rescued strays and funded shelters. He played charity football to raise medical funds for fans he had never met. He would quietly pay hospital bills, leave, and refuse acknowledgement.

That unpublicised generosity turned admiration into devotion. In a society cynical about fame, he made decency fashionable.

The Final Journey: The World’s Fourth-Largest Farewell

When the news of his death reached Assam, disbelief turned to pilgrimage. Zubeen had been in Singapore to perform at the North East India Festival. During a recreational dive near Saint John’s Island, he reportedly entered the water without a life jacket. Though pulled out swiftly, he could not be revived. Authorities confirmed drowning as the cause of death.

His body was flown back to India under official escort. At Delhi airport, airline staff, crew members, and fans lifted the coffin onto their shoulders and sang Mayabini Raatir Bukut. In Guwahati, traffic froze. Over 1.5 million people lined the 31-kilometre stretch from the airport to his house in Kamarkuchi. Banners, flowers, and Bihu drums filled the air. It took seven hours for the hearse to move that distance.

On 23 September, he was cremated with full state honours at the Arjun Bhogeswar Baruah Sports Complex. A 21-gun salute echoed through the crowd. More than two million people attended or lined the routes in the following days. The Limca Book of Records later confirmed it as the fourth-largest funeral in global history, after Michael Jackson, Princess Diana, and Tamil leader C. N. Annadurai.

Yet Zubeen was not a global pop titan backed by billion-dollar machinery. He was a regional artist who sang mostly in Assamese. That millions came unprompted was not hysteria; it was gratitude.

They had lost not just a musician but the conscience of their state.

Fearless Honesty, Flawed Humanity

Zubeen’s greatness lay not in perfection but in the courage to stay unvarnished. He spoke his mind even when it cost him. He criticised corruption, joked about politicians, and mocked self-importance. When militants banned Hindi songs at Bihu, he sang them louder.

His public defiance sometimes sparked outrage. He once declared Krishna was “a man, not a god.” Religious groups protested, yet he clarified that his intent was to humanise myth, not insult faith. The same people who shouted at him one day would sing with him the next. Assam forgave him because it knew his rebellion came from love.

He never hid his battles with alcohol or exhaustion. In doing so, he normalised vulnerability in a region where artists were expected to be flawless. He reminded people that imperfection is also truth.

Music connecting people sans borders

Assam is a land of forty languages, thirty ethnic groups, and decades of unrest. Zubeen turned that complexity into harmony. His concerts became public squares where tribes, castes, and classes met under one rhythm. He could move from a Bodo folk tune to Hindi pop within a minute, and no one felt alienated.

He connected Bodo villages, Bengali settlers, and tea-garden workers through melody. In a state torn by identity debates, his songs reminded people that belonging could be plural. For many, he was the only public figure who could be loved by both sides of any divide.

This is why his passing felt not just emotional but existential. When Zubeen died, Assam lost the man who made everyone feel they belonged to the same song.

The Song that Became a Prayer

Before his death, he often joked that when he was gone, people should sing Mayabini Raatir Bukut. The line was half prophecy, half jest.

After the news broke, that very song became a mass requiem. From mobile loudspeakers to candlelit vigils, its melody carried across valleys and villages. When his coffin arrived in Guwahati, even airport workers held it high and sang. During the cremation, as priests recited mantras, the crowd’s voices overpowered them with Mayabini.

The song that once described romantic yearning had turned into a hymn of collective farewell. In that moment, art achieved what politics never could: absolute unity.

The Investigations and the Aftermath

His death sparked formal investigations in both Singapore and Assam. The state government formed a Special Investigation Team to examine whether safety lapses occurred during the festival. Early findings suggested inadequate supervision and poor emergency response. Arrests followed.

For fans, however, no legal report could fill the silence he left behind. Government committees planned memorials in Guwahati and Jorhat. Streets were renamed, and schools proposed including his songs in music syllabi. Across the diaspora, from London to Dubai to New Jersey, cultural groups held simultaneous memorial concerts.

Even in tragedy, Zubeen united a people scattered by distance.

Philanthropy and the Quiet Hero

Away from cameras, he practised kindness as a habit. Through the Kalaguru Artiste Foundation, he funded school fees, flood relief, and medical aid for retired artists. During COVID-19, he converted his two-storey home into a quarantine centre and personally distributed medicines and food.

He played charity football matches to raise funds for hospitals and animal shelters. He was often seen in Guwahati’s poorer neighbourhoods, handing out cash or groceries anonymously. He disliked ceremonies, saying, “If you help someone, don’t call the press. Let God notice, not people.”

That humility deepened his moral authority. He showed that celebrity could still mean service.

A Non-Political People’s Leader

Perhaps the most striking paradox of Zubeen’s life was that he became a people’s leader without office or manifesto. He never stood for elections, yet his voice could move policy. When he demanded better cultural funding, budgets shifted. When he sang against divisive politics, crowds listened.

He reminded citizens that conscience matters more than slogans. In a world where activism often depends on party patronage, he proved that authenticity alone can lead. Ministers sought his endorsement; he gave them silence instead. That silence spoke louder than any speech.

The Symbol of a Generation

For those who came of age in the 1990s and 2000s, Zubeen’s songs were emotional geography. College romances began with Anamika tracks, heartbreaks ended with Mayabini, and protest marches borrowed his lines as chants. No other modern artist infiltrated daily Assamese life so completely.

Students studied to his love songs, farmers played his Bihu beats while harvesting, and newly-married couples danced to his soft ballads. For an entire generation, his voice was background and backbone.

Among the Assamese diaspora scattered across continents, his music remains a bridge to home. On the night of his death, candlelit vigils appeared simultaneously in London, Sydney, Doha, and Toronto. People who had left home decades ago sang his songs together online.

He had carried Assam to the world, and now the world was carrying him back.

A Cultural Ambassador Forever

Zubeen’s story transcends geography. He was born in the hills of Meghalaya, made in the towns of Assam, and loved across India and the diaspora. He carried the rhythm of the Brahmaputra wherever he went, teaching the world that culture is not a product of power but of passion.

He sang for films in Mumbai, folk shows in Sivasagar, and peace concerts in Kathmandu. He spoke in broken Hindi but fluent emotion. He reminded the rest of India that the Northeast was not a margin but a pulse.

Even when his national fame peaked, he kept returning to Assam’s smaller towns to perform free concerts. He said, “If people cannot afford tickets, I will bring the stage to them.” That humility made him a cultural ambassador far more credible than any official envoy.

He made Assamese lyrics trend on Indian radio, inspired fusion bands, and helped a generation believe that their dialects deserved microphones too.

After the Music Stops

Weeks after his cremation, thousands still gathered at Kamarkuchi daily. Some came to sweep the cremation ground because “Zubeen liked cleanliness.” Others sang his songs in the open air. Walls in Guwahati bloomed with murals of his face; shops kept his photograph beside gods.

Children who never met him now learn his songs in schools. His melodies echo in classrooms, wedding halls, protest grounds, and diaspora gatherings alike. The grief had matured into reverence.

What does it say about a man when a state of thirty-five million mourns him like family? It says he gave them belonging.

Legacy in Numbers and Spirit

Over thirty-three years, Zubeen recorded more than 38,000 songs, acted in over thirty films, directed four, and composed for twenty. He played twelve instruments, sang in forty languages, and won two National Awards for Best Music Direction (Mon Jaai, 2008; Echoes of Silence, 2009).

He received multiple Assam State Film Awards, a GIFA Award (2006), and an honorary Doctor of Literature from the University of Science and Technology, Meghalaya (2024). His films Mission China and Kanchanjangha set box office milestones, together earning over ₹13 crore.

He was the first Assamese artist to perform in Trinidad and Tobago, and Mayabini Raatir Bukut was once played by the US Air Force Band during a cultural ceremony,proof that music from Assam could travel beyond maps.

But awards and numbers only tell half the story. His true legacy lives in the emotion he awakened,the pride of a region long treated as peripheral, the confidence he restored to a generation told they were invisible. He made ordinary people believe their language was enough to reach the world.

The Personal Glimpse

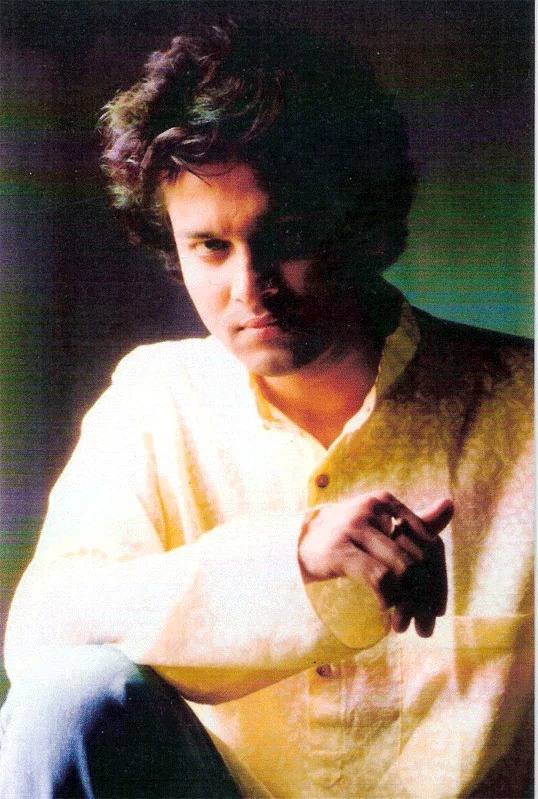

Behind the noise and lights, Zubeen was a family man. He married fashion designer Gargi Baruah in 2002, and they remained devoted companions through his turbulent schedules. Friends recall him cooking fish curry after concerts, sketching between recordings, and rescuing street animals late at night.

He loved football, painting, travel, and long drives to nowhere. His home was filled with stray dogs, guitars, and unfinished canvases. He called them “my orchestra of silence.”

Those close to him describe a man who feared loneliness more than failure, who wrote songs on scraps of paper and tucked them behind books. Fame never made him guarded; it only made him generous.

Even in his last months, he was planning collaborations with younger artists and drafting an Assamese musical that would bring classical and rock together. The dream ended mid-note, but his unfinished ideas have since been turned into tributes by those he mentored.

The Symbol of Courage and Conscience

Zubeen’s story is more than art; it is about integrity. He showed that one can speak truth to power without hatred. He stood for causes without carrying banners. He believed that dissent, when born from love, heals rather than divides.

In an era of quick fame and algorithmic applause, he remained fiercely analogue, his music recorded in emotion, not machines. He sang with imperfections intact, reminding listeners that humanity, not polish, is what makes a voice unforgettable.

To the world beyond Assam, his life is a case study in how cultural courage can reshape a region’s destiny. To his people, he remains an older brother who never left.

Epilogue: The Last Homecoming

As dusk fell on 23 September 2025, the flames of his pyre turned gold against the evening sky. The crowd began to sing again, “Joi Zubeen.” Children climbed shoulders to see the smoke rise; elders folded hands and whispered blessings.

When the last embers cooled, Assam felt emptied yet strangely complete. Because Zubeen had done what few could, he had given his people a soundtrack to believe in themselves.

He proved that one man’s song could carry a state’s soul to the world. He showed that an artist can lead without office, heal without sermon, and belong to everyone without belonging to any.

Zubeen Garg’s life was not about perfection but about presence. Not about politics but about people. He left behind not silence but resonance, a reminder that when music is born of honesty, it never truly ends.

Timeline: The Journey of a Lifetime (1972–2025)

1972 – Born in Tura, Meghalaya, to Mohini Mohon and Ily Borthakur

1975 – Gave first public performance at age three

1989 – Completed matriculation; joined J.B. College, Jorhat

1992 – Released debut Assamese album Anamika

1994–96 – Released Asha, Pakhi, Maya, Chandni Raat; became a household name

2000 – Directed first Assamese film Tumi Mor Matho Mor

2002 – Married fashion designer Gargi Baruah

2006 – Sang Ya Ali in Gangster; won GIFA Award

2008 – Won National Award for Best Music Direction (Mon Jaai)

2014 – Released Rodor Sithi, redefining Assamese cinema aesthetics

2017 – Mission China broke regional box office records

2019 – Kanchanjangha surpassed previous records

2021 – Opened his home as a COVID-19 care facility

2023 – Acted in Dr. Bezbarua 2

2024 – Received Honorary D.Litt. from USTM

2025 (Sept) – Passed away in Singapore during a concert tour

2025 (Sept 23) – Cremated with full state honours; two million mourners attended

Legacy in Numbers (Infobox)

| Category | Details |

| Full Name | Zubeen Borthakur (Stage Name: Zubeen Garg) |

| Born | 18 November 1972, Tura, Meghalaya |

| Died | 19 September 2025, Singapore (aged 52) |

| Occupation | Singer, Composer, Lyricist, Actor, Director, Philanthropist |

| Songs Recorded | 38,000+ across 40+ languages |

| Films (Actor/Director/Composer) | 30+ / 4 / 20+ respectively |

| Languages Sung In | Assamese, Hindi, Bengali, Bodo, Nepali, Tamil, Bhojpuri, English, and others |

| Awards | 2 National Awards, GIFA (2006), Assam State Awards, Honorary D.Litt (USTM 2024) |

| Box Office Milestones | Mission China ₹6 crore, Kanchanjangha ₹7 crore |

| Social Work | Kalaguru Artiste Foundation, COVID relief, education aid, animal welfare |

| Hobbies | Painting, Football, Cooking, Travel, Animal Care |

| Favourite Song | Mayabini Raatir Bukut |

| Philosophy | “Art is freedom, and freedom belongs to the people.” |

By Wynona M

Disclaimer: This feature is an original editorial article written exclusively for The WFY Magazine (November 2025 Edition). It is based on verified public information and independent research available at the time of writing. It does not include direct quotations from individuals and is intended purely as a journalistic tribute to the late artist Zubeen Garg.