Daya Bai The Textbook of Mercy ! A Life Extraordinaire: Love Sans Borders

Daya Bai is a social activist from Kerala who has been working among the tribals of Madhya Pradesh for over fifty years. Mercy Mathew, aka Daya Bai, comes from a prosperous Christian family in Pala, Kerala. She was born in 1940 as the eldest of 14 children of Mathew and Elikutty. She had quite a happy childhood and a firm belief in God. Her desire was to become a nun. Her speeches, satyagrahas, campaigns, and work to pressurise the local government leadership to start schools have helped a lot in uplifting the standard of living of the Scheduled Tribes in the neglected remote villages of Madhya Pradesh. She has been associated with the Narmada Bachao Andolan and the Chengara agitation. She led solo struggles, representing the forest dwellers and villagers of Bihar, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and West Bengal. She just ended her hunger strike demanding justice for the endosulfan victims of Kerala.

Daya Bai – Early life and education.

She had her primary education at Kochu Kottaram Primary School and Valakkumadam St. Joseph High School. She graduated in biology and earned MSW and law degrees from the University of Mumbai. She reached the tribal regions of Madhya Pradesh for fieldwork as part of her MSW project. Later, she chose this region as her workplace.

Mercy dropped out of her eleventh grade and decided to become a nun. Disgusted with the luxuries and comfortable life of the nunneries in Kerala, she came to the Holy Convent in Hazaribagh, Bihar at the age of sixteen, feeling that she could do something for the downtrodden in North India.

Daya Bai’s calling

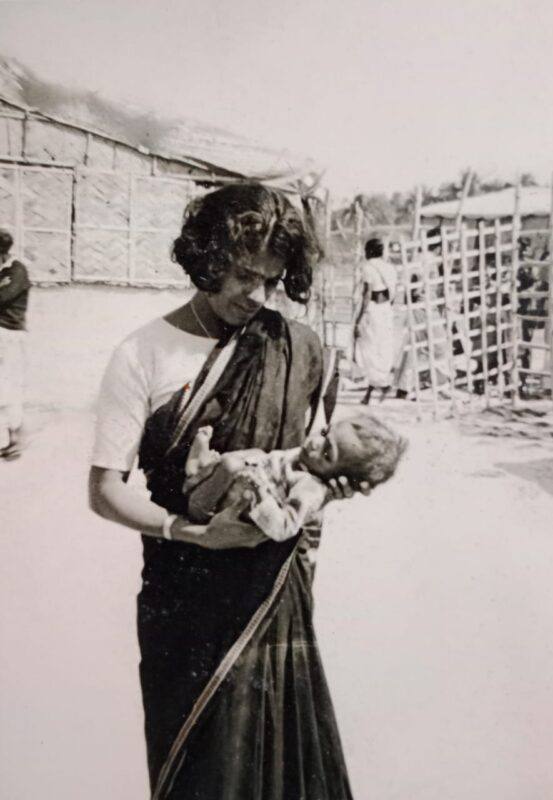

Mercy was touched and realised the suffering and separation of the adivasis who come to Holy Mass in the pouring rain, carrying their children, covering their bodies with a single garment, while the convent residents celebrate Christmas festively, with various cakes and sweets. When Mercy’s request to go to the tribal village was ignored, she left the monastery without completing her training.

She worked as a teacher for one and a half years in Mahoda, a tribal area of Palama district in Bihar. In the meantime, she completed her graduation with a B.Sc. degree. She then became a teacher in one of Jabalpur’s English-medium schools, where she worked for a year and a half. She later came to Kerala and worked for the poor in an institution run by a bishop. Mercy left the place and came to Mumbai after facing harassment at the hands of a priest. There she wandered around for a while, and during this period she learned tailoring.

She also worked at Mother Teresa’s Children’s Home and Old Age Home. She found it hard to get along with the lifestyle there. During the war, she reached Bangladesh to serve the refugees of the war. When she encountered the horrors of the war, she realised that her path was not the one that was structured within the orientation of the church. She then decided to find her own path and calling in life. She strongly felt that the true calling of Christ is different from the ones that are practised conventionally.

When asked about her relationship with Mother Teresa, she stated that she had a beautiful experience with the Mother but did not want to follow in her footsteps. Daya Bai stated unequivocally that she believed in Christ but not in the Church’s authority.

Daya Bai’s Pursuit

Her quest for her true calling in life brought her to Tinsai. Mercy had lived in Sullagappa in the Chintwadi district. Chandra was her neighbour then. This Tinsai village is the tribal area where the mother of Chandra lived. The natives of the region were the royal descendants of the Gond dynasty. These tribals, known as Gonds, were living in very poor conditions, largely neglected, and their needs were never addressed.

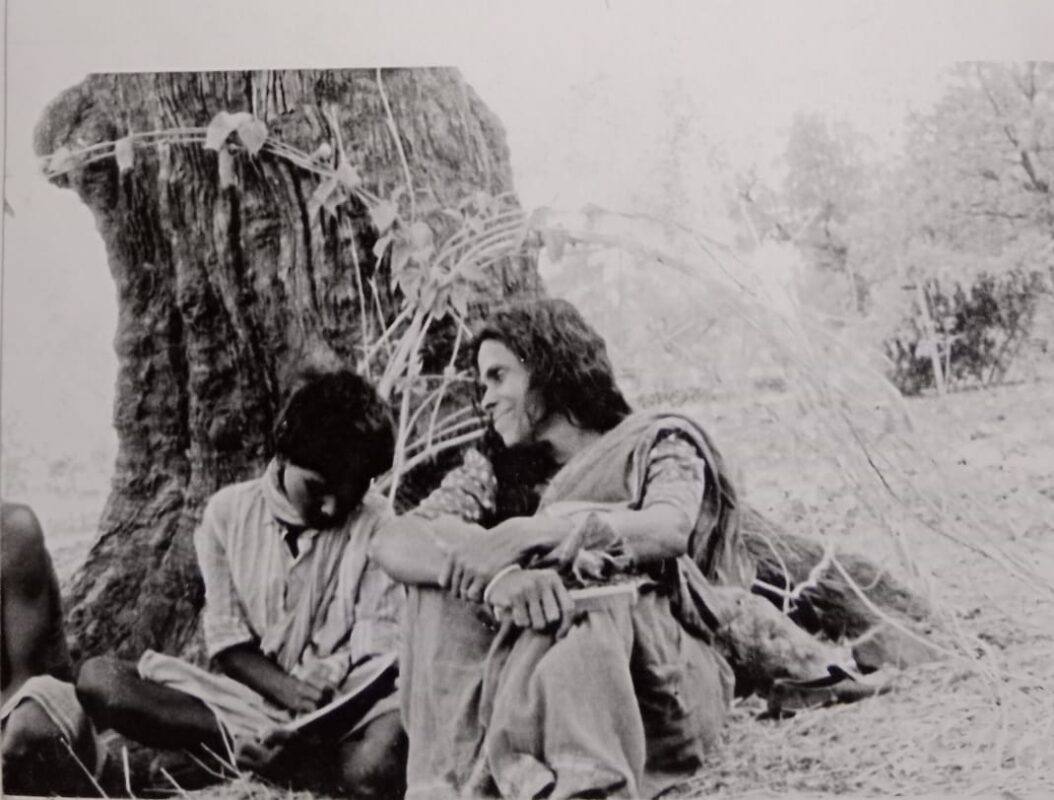

It’s just that she barely had enough money to take a train up to a small town in Madhya Pradesh, from where she decided to walk (25 kms!) till her feet could take no more. That’s how she came to Barul. That place became her home for the next 15 years. She worked with the tribal communities here, sleeping on the verandahs of those who let her in at night and eating whatever they generously gave her. There were no goals or, most importantly, no regrets. But being alone and without enough legal knowledge, she felt a little lost in her attempts to fight for the rights of the tribal people.

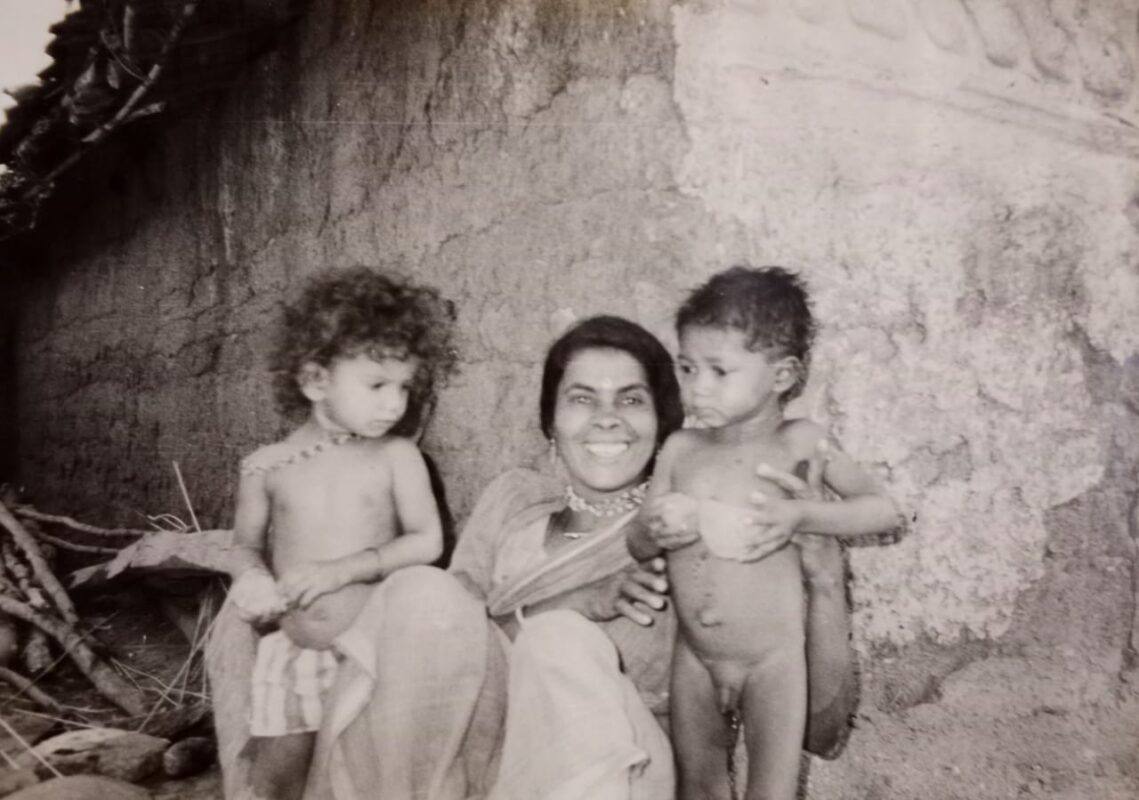

Mercy realised that the natives would only accept her if she became one of them. She adopted their dress, language, and food and earned their trust and love. In India’s vernacular languages, mercy is referred to as daya, and the tribal woman is referred to as bai. Thus, Mercy became Daya Bai !

Mercy looks every inch, a tribal woman, behaves like a passionate maverick activist and talks like a razor-sharp lawyer. A combination that never fails to turn heads and get surprised stares.

Mercy Mathew is not really a name one expects to come across in a remote Gond village in Madhya Pradesh’s Chhindwara district. The surprise is further compounded when one meets Mercy Mathew—not because she does not fit in with the surroundings, but because she does, and so well that one can easily pass her without a second glance, assuming her to be one of the locals.

This is not something that came easily to Mercy; it was in fact the result of much conscious effort. For example, she changed her name to ‘Daya Bai’, a loose translation of Mercy, and a name that is fairly common in this area. She has been living in the tribal hamlet of Barul for many years now, and has been fighting along with the tribals for their rights, often risking her life in the process. When she first came here, she was determined to share the life of the tribals with all its trials and tribulations; only thus would she be able to serve them effectively. On my first day in the village itself, someone asked me why I came there and did I think that they were the monkeys of the jungle? “

This statement underscored the importance of bridging the gap between the tribals and herself and initiated a process to which Dayabai attaches great importance—declassing. Bridging the great divide entailed “lowering my identity and raising theirs. It meant declassifying and getting smaller. ” And, as her life today demonstrates, Dayabai plunged further into the process with the utmost commitment and perseverance.

As the villagers in Tinsai (where she lived earlier) and Barul (the village where she now lives) accepted her into their lives, Dayabai acted on her conviction that improving the self-image of the tribals was the key to improving their lot. This meant making them aware of their rights and joining with them in the struggle to ensure that those rights became reality.

As is only to be expected in a forest area, one of the main exploiters of the tribals here was the Forest Department. Wages were paid irregularly, and a certain amount would be kept back as a “cut” for the forest officials. Dayabai got the local people to insist that full wages be paid on the spot after a day’s work and not after a few days at the marketplace, as had been the earlier practice.

Another related struggle was over tendu leaves. When the tribal women were not getting proper wages, Dayabai explained that if they allowed the forest officials to take away the tendu leaves that they had collected, they would never get paid properly. Dujiya, an elderly woman in Tinsai village, belonging to a sub-caste engaged in animal husbandry, tells the story, “When the truck came in the night, Bai called me first. I called the women, and we gathered where the tendu leaves were kept. Galobai and other women sat on the bags full of leaves, so the officers couldn’t take them away. We made a circle like a chain, holding our hands around the bags, and we sang. Bai taught us a lot of things and stood with us to fight for our rights.

Getting the people to stand united on such issues was not easy. To get the people together, she would tell them a story about four brothers and illustrate it with a bundle of sticks. Each stick can be broken separately, but if they are tied into a bundle, it becomes impossible to break. “United we stand, and divided we fall!”

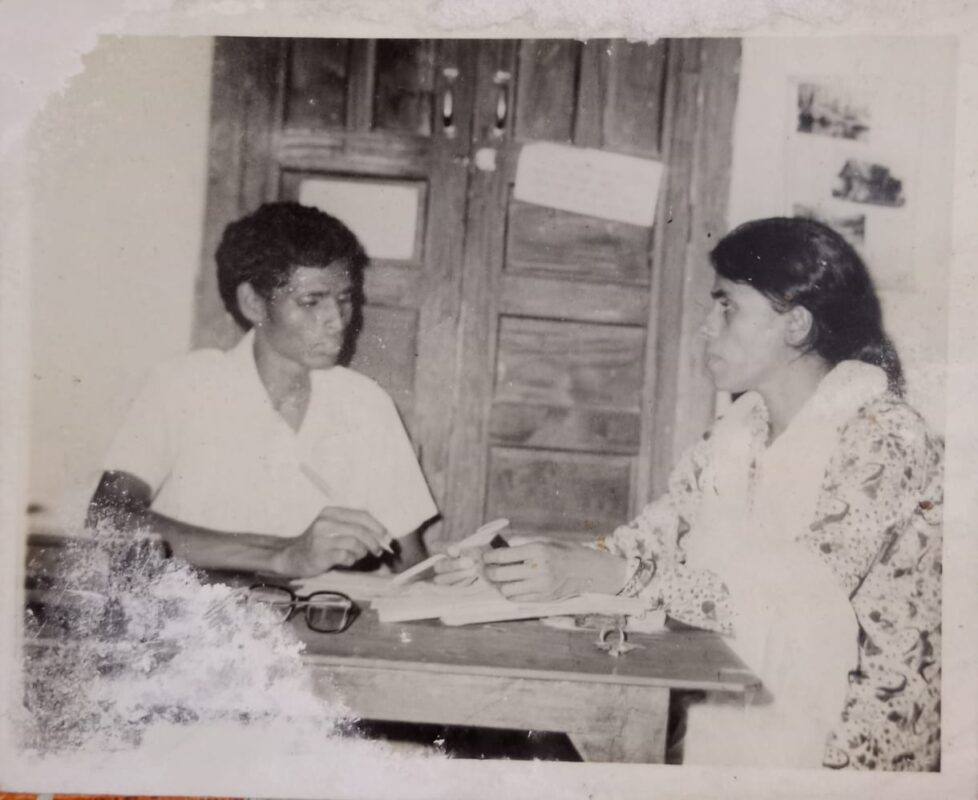

The women from the village said, “She taught our children reading and writing.” Daya Bai set up a school in the Barul village. Daya Bai visits each village and teaches them how to care for themselves before moving on to the next.

Daya Bai brought the tribal people together and encouraged them to stand up for their rights. Nefarious village brokers took advantage of a ‘anudan’ (subsidy) scheme intended for tribal people and the poor.

The scheme blew up in their faces when beneficiaries started receiving bank notices asking them to pay up amounts double the size of the ‘subsidy’ amount or face recovery proceedings.

Daya Bai found that more than half of the inflated amount contracted as a “loan” in the name of the beneficiaries was spirited away by middlemen. She was told that this had been the practise for quite a long time, which rendered the tribal poor easy pickings for loan sharks and moneylenders.

Daya Bai established the Swayam Sahayatha Group in the late 1990s, long before the idea became popular as a tool for poverty alleviation. This incurred the wrath of the middlemen, moneylenders, and the village elders. She urged female bank officials to use their positions to help the oppressed and distressed poor.

Her laborious efforts eventually drew the attention of the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development’s nearest representative office (NABARD).

Senior officials of the Gramin Bank visited the village and decided to offer the community members a SHG credit line. It was a brilliant start, as State Bank of India officials followed up and offered to open a branch in the village.

Daya Bai urged women officials gathered at the All-India Bank Officers’ Confederation’s fifth state conference to use their ranks to help the oppressed and distressed poor.

Daya Bai, Knowing Her Better.

Daya Bai was subjected to verbal abuse on a KSRTC bus, which resulted in the suspension of two KSRTC employees, and this has been the topic of discussion for quite some time. This was Kerala, her home state.

Mercy Mathew, aka Daya Bai’s fourth out of the thirteen younger sibling, George Pullatt, says, “the controversy, though painful, has been a blessing in disguise.”

Daya Bai has received numerous awards and numerous news articles have been published about her; she has dedicated her life to the people, but until this heinous incident, no one in her home state had heard much about her.

Would we remember Jesus Christ and his contributions as fondly today if he had died naturally at the age of 90 rather than being crucified, or if Gandhiji had not been shot dead? “Abuse is sometimes more potent than awards,” says George.

George asserts to be the closest brother to Daya Bai, as well as the two have a special bond. “When she decided to join the convent, I was studying in Class III. She came to our school to distribute toffees to all the schoolchildren before departing, since no one from our area had ever left such a distance to work in a congregation before, ” he says. That was my first memory of her. Even when she chose to leave the congregation and work as a social worker, there were no major problems at home. In our country, however, women who left the convent or were expelled from the convent are derogatorily referred to as Madamchadi and are regarded as a liability to their families.

This fear, combined with her wish to work in Madhya Pradesh’s rural communities, compelled her to not come back. Mercy’s name was changed to Daya, and Bai was provided as a mark of respect. Because of this name, many never realised that she was a Keralite until now, ” he adds.

A couple of years ago, her father passed away, and she was forced by her family to take some money from his will. She decided to buy a little piece of land with this, and built, for the first time, her own home.

Simultaneous with all her social activism, Dayabai has also developed a keen interest in organic farming. On the small plot of land that she owns, she has set up an eco-farm and has been spreading knowledge and techniques of organic farming among the people.

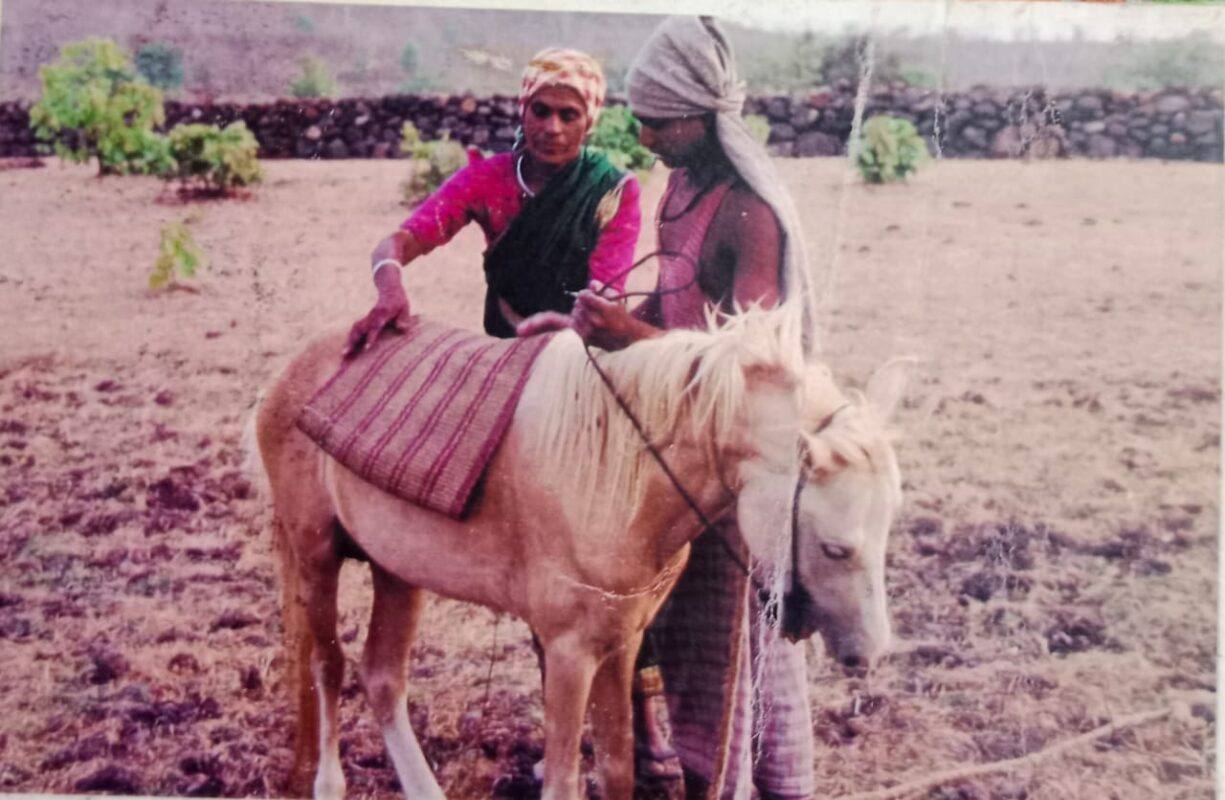

In the village, she has a mud house, which is cool and welcoming under the hot summer sun. She has an extended family of chickens, cows, some cats, a little pony and her dog, Athos. She speaks with them about everything, and they appear to comprehend and react with love. Her possessions, apart from the basic knick-knacks of a minimalist, are a bright red solar cooker, a self-made compost pit for bio-gas, and a small well. She does have a small plot of land on which she cultivates wheat, pulses, and a few vegetables like tomatoes.

Daya Bai is a masterful performer who has consistently believed in the power of street theatre to educate the public. She throws herself completely into her acting, and watching her perform is not an experience that is easily forgotten. Dayabai has developed street plays on various issues, including alcoholism, the environment, and communalism, and has found them an effective means of getting people thinking about and acting on these issues. She has authored books like ‘Pachaviral’ and penned songs which are quite popular and vibrant with earthly fragrances.

The successes in uniting the people and helping them win their rights have not come without a price to her. Dayabai has often been beaten up by the police during various struggles. In 1999, she was badly injured when she was beaten up by the police when she went to register a complaint at the police station.

Another issue in which she is totally involved is the fight against communalism. She visited Gujarat after the 2002 riots and was shattered by the experience. She went around the villages, telling people about what she had seen and discussing with them how communalism could be fought in their villages. In 2002, the National Alliance of People’s Movements (NAPM), along with grassroots movements all over India, organised a peace walk from Chitrakoot to Ayodhya. People of all beliefs joined in the march, and Dayabai pitched in with gusto. Basing herself on what she had seen in Gujarat, she used her street theatre skills to good effect in a mono-play. She would appear on the stage and say, “I have brought a woman with me from Ahmedabad,” then turn around and reappear as Sidabana, whose tragic story she would then recount in her passionate style: “I am the only one surviving in my family. My own daughter was raped in front of me. She was like a flower. My husband and all family members were butchered. I was also raped and have only one hand now. Friends, now I want to bring peace and harmony among people. “

She is invited by various social and spiritual institutes as a visiting professor. She gives training on street theatre, and is a much sought-after resource person by different NGOs and social movements. She received the National Award for Social Work from Dharma Bharati in 2001. There has also been some derision-as Father Prakash Lohale, a Dominican priest, says, “When we were doing our training, Dayabai was one of the people who spoke to us. She told us about the need for declassing and sharing the lives of the common people. We thought she was crazy and laughed at her; it wasn’t until later that we realised the significance of what she was saying. I wish I had listened to her more carefully then. “

Through all this, she has remained the simple, unspoiled person she always was. Meeting her and spending time with her can be a humbling experience—it is rare that one has the opportunity to meet somebody with this combination of sacrifice, dedication, humility, and serenity.

Awards

- Daya Bai was named the Vanitha Woman of the Year in 2007.

- In January 2012, she received the Good Samaritan National Award (established by the Kottayam Social Service Society and the Agape Movement in Chicago).

Legacy

Shiny Jacob Benjamin’s ‘Ottayal’, or ‘One Person,’ is a documentary film about Daya Bai. Nandita Das, a film celebrity, penned a tribute to her as her life’s inspiration in 2005.

Her remarkable story has recently been told in a fascinating book and video film, produced by Annie Drese. In the book, Daya Bai writes, “I began to bridge the gap between the people and myself. It meant taking on a totally different kind of lifestyle. Having had no financial support for several years, I had to struggle to earn my livelihood and also to economise. There were occasions when I could not afford a meal and so managed with a piece of jaggery and water. However, I noticed that I was never in need of anything in particular.”

Films

She played the lead role in the movie Kanthan – The Lover of Colour 2021.

Kanthan – The Lover of Color is a Malayalam film made in 2018, directed by Shareef Eesa and written by Pramod Kooveri. Daya Bai, along with Prajith, portrays important characters in the film. The film received the Kerala State Film Award for Best Film in 2018.

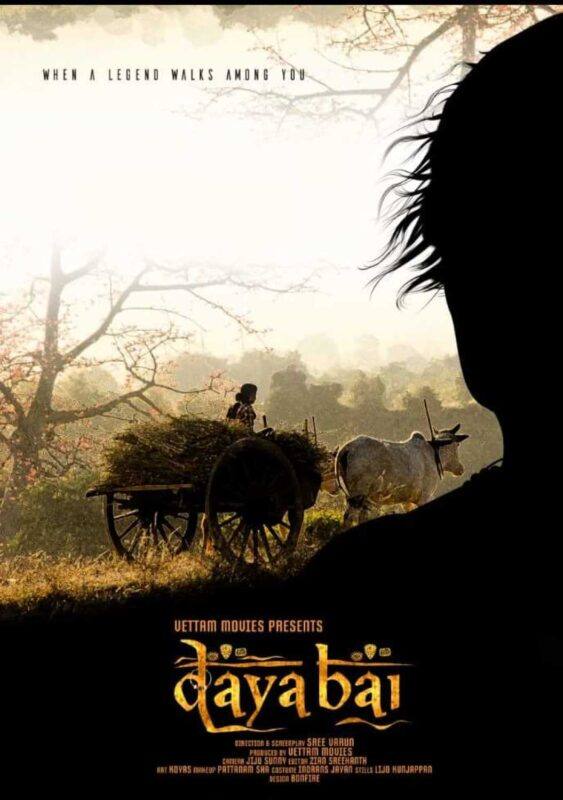

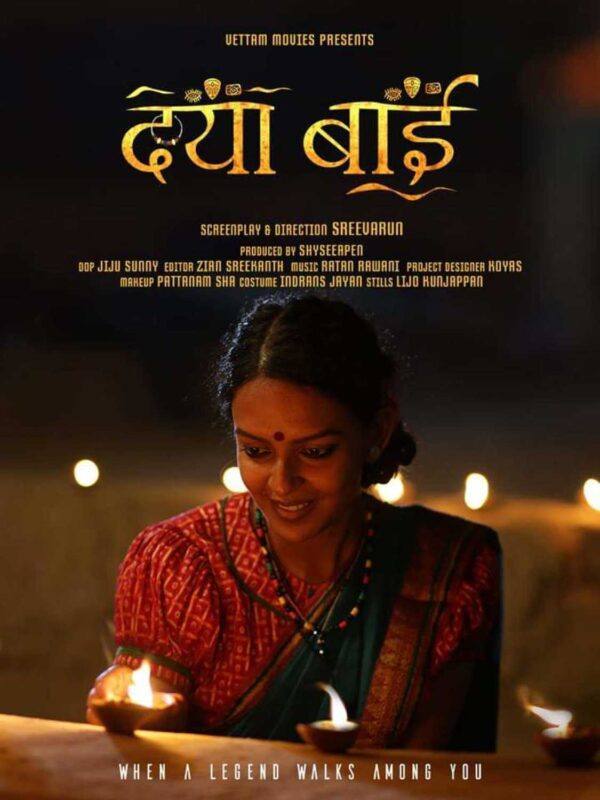

A biopic film on her is titled, “Daya Bai.”

Daya Bai is a Hindi feature film starring Bidita Bag as Daya Bai. The movie is directed by Sree Varun and produced by Shyse Eppan and Vettam Movies .

We spoke to Varun, the director of the biopic, to find out what inspired him to make a film about Daya Bai’s life.

“I discovered Daya Bai while pondering what to do next after my first film,” Varun explained. All I had in front of me was an insatiable desire to know more about her and a book called “Pachaviral”. I rediscovered her through my film Daya Bai.”

“How did Kottayam-born Mercy Mathew change to Daya Bai when she landed in Madhya Pradesh? That was the most troubling question for me. But that mother very calmly showed me the answer. I witnessed the transformation of Daya Bai from Mercy Matthew. When Mercy Mathew arrived in Madhya Pradesh from Kottayam, she became a completely different person named Daya Bai. Today, she is the guardian angel of many people who were supposed to be the bride of Christ. When I approached Daya Bai for my film, she gave me permission after a day by understanding my intention. Later, I started travelling with Daya Bai for my film. We retraced each of the parts she came through. In a way, those trips were a look back at her own life. I have seen those eyes widen with joy and sometimes even tears as she shared with us many good and bad experiences,” he continued.

Varun was overwhelmed to see the warmth Daya Bai received from the people when they travelled through the villages of Madhya Pradesh. He describes it as a huge achievement, quite an unprecedented one.

“When I witnessed the fondness of its people, I began wondering why we Keralaites completely missed Daya Bai? Those villages were a different experience for us from the people who were insulted by name for their dress without pretending to have seen it. I have felt that the energy of Daya Bai that we see in the faces of the struggle is the love that the village gives. It is not for nothing that Daya Bai states that nature and human beings are my textbook,” he said.

Varun further adds that, “After going through the film’s references, the biggest revelation that occurred to me was that she’s a textbook of never-ending experiences. A mother who loves and cares for those who have hurt her. Daya Bai once told me that Gandhiji and Christ were her gurus. Both of them called for patience and tolerance. Movies should be living lives. Daya Bai is the biggest example. A fantastic example of tenacity and fighting spirit. If you want, you can say that Madhya Pradesh and the nunnery moulded her for this purpose. Many of the shooting locations in my film are actually the roads that the mother used to walk. Daya Bai used to visit there on many days of shooting. One of the moments that touched me the most was Daya Bai’s friend Ponthal’s scene, and I still remember Daya Bai’s face, crying while we were shooting the scene. I believe that is a testament to the extent to which Daya Bai was in touch with the people there. I consider it a blessing in my life to be able to travel with this mother-Daya Bai. The film Daya Bai tells the life of Daya Bai without the spices of cinema. “

Varun concludes, “Even at the age of 82, Daya Bai remains with us as one of us, with an unquenchable fighting spirit and endless affection. We read the stories of historical heroes, but I pray to the lord that our mother, ‘Daya Bai’, remains in history forever as a textbook for all of us to learn how to live! “

I would like to conclude by quoting Daya Bai, “Working and caring for people is not work for me, it’s simply life.”

She further adds, “It is not a sacrifice… it is more than that… it is the only way I know for sure that I can live and really be happy! Not living this life, not doing what I do, would in fact be a huge sacrifice. “

I know for sure that if she was given another life, she would live it the same way all over again.

-Melwyn

I love looking through an article that can make men and women think. Also, thank you for permitting me to comment!

Saved as a favorite, I like your blog!

You are so interesting! I don’t suppose I have read a single thing like that before. So wonderful to find another person with a few genuine thoughts on this subject matter. Seriously.. thanks for starting this up. This website is one thing that’s needed on the internet, someone with a little originality!

We are a bunch of volunteers and opening a neew scheme in ourr community.

Your sie provided uss witth useful information to woork on. Youu have done aan impessive job and our whole community will prdobably bbe

thankful to you.

Woh I love your articles, bookmarked! .