Know The Truth About The US Laws That Hindus Faced.

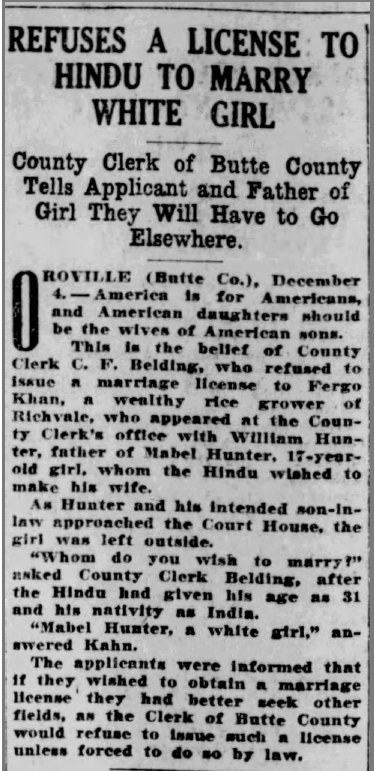

From the early twentieth century onward, US immigrants of South Asian origin—referred to as ‘Hindus’—had to deal with regulations in several states prohibiting ‘interracial’ marriages. The repeal of ‘Jim Crow’ legislation started in the late 1940s. In 1919, the county clerk in northern California’s Butte County refused to grant Fergo Khan, a wealthy ‘Hindu’ rice farmer, a licence to marry Mabel Hunter, a ‘white’ girl, because ‘American daughters should be the wives of American sons, and that America is for Americans’ (Sacramento Bee, 4 December 1919). In a variety of ways, the ruling reflected the extremely contentious climate surrounding interracial marriages at the time.

Two years earlier, in 1917, the Immigration Act, sometimes known as the ‘Barred Zone Act,’ severely restricted immigration to the United States for persons claiming to be from a wide range of Asian territories. For the ‘Hindus”—a misnomer once often used for all South Asians—who were already living in the United States, this just added to their uncertainties. In recent years, several of them have been given naturalisation on the basis that they are ‘Caucasian,’ and thus ‘free and white’ under the US Naturalisation Act of 1790. However, objections to such verdicts had surfaced. This ‘ambiguity’ allowed the county clerk, the district official in charge of managing and maintaining public documents as well as issuing licences, significant discretionary power.

In 1921, The Sacramento Bee, a California newspaper, reported on the marriage of a Hindu, Harry Sahato, to a white girl, Grace Ida Bahrs, in Martinez, Contra Costa County, in the San Francisco Bay area, which caused an uproar. According to the county clerk, Hindus were Caucasians under recent legal rules, and there was no reason to prevent the marriage. According to California marriage and ‘miscegenation’ legislation, interracial marriages were only prohibited between ‘negroes, mulattos, and Mongolians’.

The portmanteau word ‘miscegenation’ is derived from the Latin terms ‘miscere’ (mix) and ‘genus’ (race or type).

Some months later, in 1923, in Yuba City, northern California, the local justice of the peace officiated the marriage of 17-year-old Julia Fernandez, described as a “pretty looking Spaniard,” and Gamon Khan, a much older ‘Hindu’. However, the marriage would cause a lot of controversy in the coming years.

Julia left her spouse in 1929, ending their six-year marriage. Her spouse suspected her of having an affair with a San Francisco stockbroker. Julia Fernandez, for her part, sought to annul her marriage in a variety of ways. In 1929, she accused him of bigamy, claiming that Gamon Khan had already married in India and had concealed this from her, and then again in 1932, arguing that the marriage was invalid since Gamon Khan was not Caucasian.

The Plumas County court that heard this case clarified the law with finality, using California’s miscegenation legislation of 1850, as revised in 1880 and 1905: Gamon Khan was Caucasian. As Mexicans were also considered white under state law, this made the marriage legal and rendered Gamon Khan white.

Miscegenation: The Beginnings

Two New York City journalists coined the term miscegenation’ in 1863, just before the 1864 elections near the end of the American Civil War (1861–1865), which pitted then-President Abraham Lincoln of the National Union Party (a coalition of Republicans and Democrats who supported the Civil War) against the Democrat candidate, George B. McClellan. Two New York City journalists created a brochure extolling the merits of ‘ethnic mixing’. The portmanteau word ‘miscegenation’ derives from the Latin terms ‘miscere’ (mix) and ‘genus’ (race or type). The pamphlet was a ‘literary prank’ meant to raise awareness about racial equality. Since then, ‘anti-miscegenation’ has become a commonly used term to describe policies and legislation that prohibit interracial marriages and partnerships.

Anti-miscegenation was a contentious subject among South Asians, sometimes known as ‘Hindus’.

Several American states had interracial marriage laws in effect in the 17th century, which were widely considered to prohibit unions between whites and blacks in the United States. Several states abolished such statutes over the next century. However, after Congress abolished slavery in 1865 and the 14th Amendment guaranteed blacks ‘equal protection under law’ in 1868, numerous states found grounds to revise and resurrect their anti-miscegenation laws.

Anti-miscegenation laws exacerbated the segregation and other ‘Jim Crow’ laws that plagued large areas of the country, particularly the south and central United States, in the post-Civil War era. ‘Jim Crow’ laws, named after a minstrel play, were a catch-all term for municipal and state laws that restricted blacks rights such as voting, civic participation, education, and employment.

Early anti-miscegenation legislation

Approximately 30 American states enforced varied degrees of sanctions against interracial marriages, with the overall goal of preserving ‘racial purity’ and the superiority of the white race. States declared marriage between whites and blacks as unlawful, prohibited certain kinds of non-whites, imposed fines and jails, and refused to recognise children from such marriages.

Florida, for example, prohibited whites from marrying people of “1/8th African or Negro blood,” declared the offspring of such marriages illegitimate, and imposed penalties including a 10-year prison term. Alabama’s statute prohibited marriage with someone who had ‘one drop of Negro blood,’ imposing prison sentences ranging from two to seven years for infractions.

In addition, two key court rulings affirmed such statutes. In Pace vs. State of Alabama (1884), the Supreme Court found that, despite the 14th Amendment’s promise of equality (equal protection by law), legislation such as Alabama’s anti-miscegenation statutes ensured that all races were penalised equally by the laws in force. Laws against miscegenation, such as Alabama’s, apply equally to all races. In the more infamous Plessy v. Ferguson case, the Court found that racial segregation laws did not violate the US Constitution if the “facilities for each race were equal in quality.” This decision upheld the “separate but equal” theory, which remained valid until the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision and 1960s legislation enactments such as the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act.

Asians are anti-miscegenation.

Beginning in the 1860s, as Chinese and Japanese immigration increased, states in the west and south modified their laws to prohibit marriages with ‘aliens’ from Asia. Deenesh Sohoni (2007) states that these restrictions initially targeted the Chinese, whose population experienced a significant increase from 34,933 to 118,746 between 1860 and 1900.

The Anti-Exclusion Act of 1882 restricted Chinese immigration, while the ‘Gentleman’s Agreement’ of 1907 curtailed Japanese emigration to the United States.

Other exclusionary policies, such as denial of naturalisation and the ability to marry, the adoption of foreign land laws, and school segregation, were prompted by the strong anti-immigrant feeling of the time, particularly in Western states. In 1958, the philosopher Hannah Arendt claimed that anti-miscegenation laws were an injustice “even deeper than the racial segregation of public schools.” “The free choice of a spouse,” Arendt contended, was “an elementary human right.”

In 1861, Nevada became the first state to establish an anti-miscegenation law that specifically prohibited marriages between whites and coloureds, including blacks, native Americans, and Chinese. Arizona’s anti-miscegenation statute in 1865 declared all marriages between white persons and negroes, mulattoes, Indians (native Americans), or Mongolians as illegal and void. The name ‘Mongolian’ quickly became more widely accepted.

As more Asians arrived starting in the 1890s, including Koreans, Filipinos, and Indians (5,008 Koreans, 5,424 Asian Indians or ‘Hindus’, and 2,767 Filipinos or ‘Malays’ in 1910, according to Sohoni), authorities also subjected them to discriminatory measures.

From 1909 to 1923, South Asians were involved in numerous noteworthy trials where they argued their status as ‘high-caste Aryans’ to establish themselves as Caucasians and therefore free and white…

In total, 15 states (including the 30 that already had anti-miscegenation laws in effect) changed their laws to prohibit whites from marrying Chinese or Mongolians (which evolved to include Japanese, as court verdicts such as Saito vs. the US in 1894 established). As migration from the Philippines increased, some states, including California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, South Dakota, Wyoming, and, surprisingly, Maryland, altered their anti-miscegenation laws to include Malays.

The name became widespread as a result of erroneous racial and anthropological assumptions. Carolus Linnaeus, the first biologist, classed humans in the mid-1700s based on skin colour: red, yellow, white, and black. Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, whose idea was used in some early naturalisation verdicts in the United States, improved on Linnaeus’ method in 1781, dividing humans into five categories: Caucasian, Mongolian, Negro, Malay, and American (Volpp, 2000).

Hindus and anti-miscegenation

However, among South Asians, anti-miscegenation is a complex subject with many contradictory aspects. The term “Hindus” became a restrictive category in Arizona’s anti-miscegenation statutes (1931), as well as in the eastern states of Virginia and Georgia (1927 and 1924). In other states, classifying ‘Hindus’ gave county clerks a great deal of discretionary power. For example, in California, it sometimes hinged on whether the ‘Hindu’ asking for a marriage licence learned English, appeared presentable, and wore a ‘hat instead of a turban’ —as Sikhs, who made up the majority of Indian immigration, did (The Sacramento Star, May 25, 1916).

Marriage restrictions were not enforced as strictly when it came to marriages between blacks and people of colour.

Between 1909 and 1923, numerous important cases occurred in which South Asians claimed that as ‘high-caste Aryans’, they were Caucasians and hence free and white, fitting the naturalisation standards of US statutes. This also deemed them ‘white’ under miscegenation regulations.

The pivotal 1923 US Supreme Court decision in the Bhagat Singh Thind case that South Asians were not ‘free and white’ sparked a slew of subsequent challenges. For example, California and Arizona, which had seen an increase in ‘Hindu’ immigration in recent years, were now subject to land laws that prohibited “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning agricultural and other property. Arizona viewed the ‘Hindu invasion’ as a threat, closely tying its modified anti-miscegenation laws of 1931 to its 1923 alien land legislation. In California, it caused far too many issues, particularly in cases of miscegenation.

The other South Asians

Similarly, for other ‘Hindus’ seeking a new life and a fresh start in the United States, there were ways to circumvent such rules. When it came to marriages between African Americans and persons of colour, legal limitations were not enforced as strictly, and there were instances where emigrants from South Asia were recognised as such.

The lives of these other South Asian emigrants took very different paths. Moksad Ali, a ‘Bengali hawker’ whose story appears in Vivek Bald’s Bengali Harlem, met Ella Blackmon, an African American woman (identified as ‘Black’ in lineage documents), in Louisiana, a southern state. They got married in 1895. Louisiana at the time prohibited marriages between whites and people of colour, but Ali, an ‘alien’ who had immigrated in 1888 (according to the 1900 census), called himself ‘Black’, as did the rest of his family. His three sons, Mongure, Karmouth, and Bahadur (Bardu), the latter of whom became a well-known jazz musician, were all natural-born citizens. The anti-miscegenation laws in Louisiana, which prohibited interracial marriages and declared the children of such marriages illegitimate, did not apply in this case.

Alfred de Livera, a’merchant’ from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), married Eddie Taylor in Mobile, Alabama, in 1911, after obtaining a ‘coloured’ marriage permit. Alfred de Livera eventually changed his name to Abdul Hassan and relocated to California, where he worked as a chicken farmer and extra in films such as Bonnie Scotland (1934) and The Lives of the Bengal Lancer (1935). Vaino Hassan became the first African American woman appointed to a California court bench, making history.

In 1920, Kalu Sonkur, also known as Sanai Nayak, an emigrant from Puri, Orissa (Odisha), married Gloria Zimmerman, a mulatto originally from Louisiana, in Chicago. In census records, he is listed as ‘black.’ Sonkur appeared as an extra in several films, most notably Bwana Devil (1954). The offspring of Sonkur did not encounter the same challenges, despite the hazy, ambiguous, and poorly kept records from that time. Kalu Sonkur Jr., a son, enlisted in World War II and declared himself black.

Meanwhile, new issues occurred for Hindus who became ‘aliens’ as a result of the 1923 Bhagat Singh Thind judgement. For example, Sardar Singh, a ‘rich Hindu farmer’ from Yuba City, had to travel three miles out to sea with his fiancée, Berilla Nutta, to marry. The captain of the tugboat they were aboard married them in a region that was not under California’s authority. California’s foreign land laws compelled Hindus who could not own land to lease it to their Mexican spouses, as the state’s anti-miscegenation laws permitted these marriages.

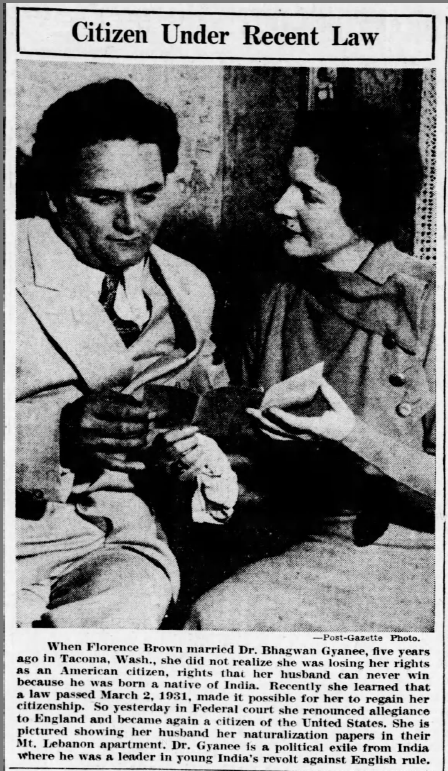

Marriages after the Bhagat Singh Thind case, such as Bhagwan Singh Gyanee’s with Florence Brown in Washington State in 1929 and Tarakanth Das-Mary Keatinge Morse’s in 1927, were more complicated. Florence and Mary lost their citizenship since the Expatriation Act of 1907 removed citizenship for women who married immigrants. Marriages in Washington and New York, where anti-miscegenation laws did not exist, carried additional legal consequences. The Cable Act of 1931–34 underwent numerous changes before restoring citizenship.

Anti-Miscegenation: The End

The first blow against anti-miscegenation laws came in 1948, when the California Supreme Court upheld Andrea Perez, a Mexican woman, and Sylvester Davis, an African American, in their choice to marry despite the county clerk’s reluctance to issue a marriage licence. The court ruled that the refusal violated the 14th Amendment. The verdict overturned California’s anti-miscegenation legislation, prompting 14 states to remove similar laws. The last blow came in 1967 with the Loving vs. Virginia case, a landmark civil rights verdict that overturned all such laws on the basis that they violated the 14th Amendment’s ‘equal protection’ and ‘due process’ provisions. The remaining 16 states immediately repealed their anti-miscegenation legislation. The Loving vs. Virginia case recently set a precedent in instances involving same-sex marriages in the United States.

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. May I ask for more information?

I do not even know how I ended up here but I thought this post was great I dont know who you are but definitely youre going to a famous blogger if you arent already Cheers

I have read some excellent stuff here Definitely value bookmarking for revisiting I wonder how much effort you put to make the sort of excellent informative website