“Warning: The Gut Microbes Facilitating Digestion Are Now Decreasing.”

Industrialized countries typically choose processed food ingredients over a higher-fiber plant-based diet.

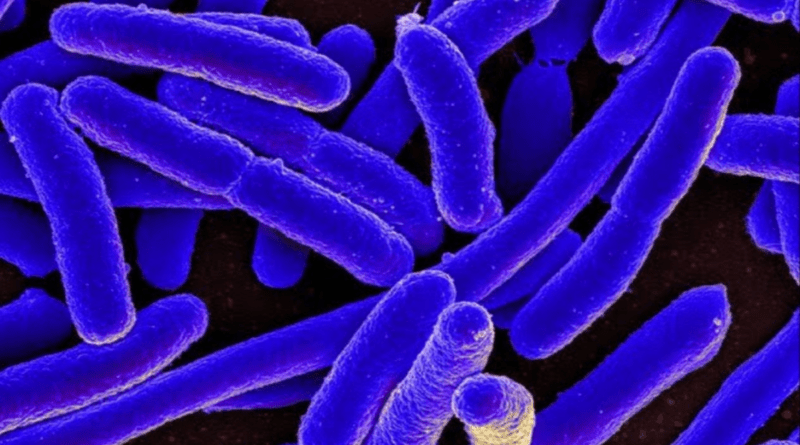

Growing processed food intake has been associated in a recent study with decreased levels of gut flora that aid in the digestion of plant cellulose, particularly in individuals living in industrialized nations.

Three novel species of cellulose-digesting bacteria in the human gut were also found by the study, which was published in the journal Science. The study discovered that these bacteria were common in hunter-gatherer tribes, early human societies, and big apes, in addition to agricultural populations.The researchers noted In the report that the loss of certain bacterial species may have an effect on energy balance as well as other elements of health.

The gut microbiota is essential for the digestion of cellulose, the primary constituent of plant fiber, in all mammals, including humans.

These indigestible substances are transformed by these microorganisms into short-chain fatty acids, which give the host energy.It was long thought that gut microorganisms that break down cellulose did not exist in humans.

It wasn’t until 2003 that researchers realized this intricate sugar molecule was really being broken down by human gut bacteria. Ruminococcus champanellensis was the species that was identified.

The majority of people do not experience cellulose fermentation or breakdown in their guts, the researchers noted, despite this finding.

Therefore, the goal of the study was to determine the prevalence of cellulose-degrading bacterial species in the mammalian gut, how well they adapt to the diet and lifestyle of their hosts, and whether the human gut contains any more of these unidentified bacterial residents.

The researchers examined samples from 75 different animal species, including ruminants and wild and domesticated primates, including macaques, baboons, gorillas, and chimpanzees, in addition to different human cohorts.

By looking for important genes, they were able to identify related species by referring to the known human strain of Ruminococcus champanellensis and the related species Ruminococcus flavefaciens, which is located in the rumen, the first chamber of a ruminant animal’s stomach.

They were discovered in 22 human and 25 rumen genomes. Three novel cellulose-degrading bacteria have been found in humans: Candidatus Ruminococcus primaciens, Ruminococcus hominiciens, and Ruminococcus ruminiciens.

Monocots, which make up a large portion of the human diet, including maize, rice, and wheat, were broken down by human microorganisms. Similarly, strains of non-human primates may break down the polymer chitin, which is widely found in insects.

More precisely, it was discovered that the human bacteria Ruminococcus hominiciens mostly lived in the digestive tracts of big apes and humans.

The researchers concluded that Ruminococcus hominiciens most likely evolved in the stomachs of ruminants and eventually colonized humans, presumably during domestication.Additionally, the researchers observed regional differences in the frequency of bacteria that break down human cellulose.

The overall prevalence was found to be 4.6% in industrialized nations like the United States, Denmark, China, and Sweden; however, among humans who lived 1,000–2,000 years ago, it was 43%; among hunter-gatherers, it was 21%; and in rural societies spread across different geographic regions, it was 20%.

This shows that these bacteria were formerly more common and numerous in human populations, but now only exist in small amounts.

“Dietary differences between industrialized and non-industrialized societies may be reflected in differences in their prevalence among human populations.”